Forerunner of the forgotten era of "printing civilization"

The forerunner of the "printing civilization" era of "Gutenberg's bright stars" is not the "book" that we are familiar with, but a kind of media that is almost forgotten today - "printed pamphlets". In the "early modern period of Europe" between 1500 and 1800, this "printed pamphlet" was not only "everywhere" but also "loved by everyone," and had a remarkable "empowering" effect: empowering the various Reformed denominations, empowering the emerging bourgeoisie, empowering the ordinary people who were beginning to read. At the same time, it plays an irreplaceable "empowering" effect on the advanced development of the whole European society: in the political aspect, it lays a tradition of political participation supported by "freedom of publication"; in the economic aspect, it opens a media economy model with "cheap orientation" as the basic strategy; in the cultural aspect, it reveals a path of cultural prosperity with "media fusion" as the important concept.

According to McLuhan's definition, the invention of Gutenberg movable type printing has epoch-making significance - constructing a "printing civilization" era of "Gutenberg's bright stars" for human beings. But Elizabeth Eisenstein, also a representative scholar of the media environment school, found a very interesting historical detail that is extremely worthy of consideration: "The book culture produced in the first hundred years after the invention of printing is not much different from the hand-written book culture of the past." The closer you look at the early machine prints of this period, the less likely you are to be impressed by the changes brought about by printing." [1] In other words, the so-called "Gutenberg star bright" is not immediately "dominant" performance.

What, then, was the "explicit" sign of the arrival of a printed civilization? It was a large-scale "pamphlet" publication.

"Flying" printed pamphlets: The "Loved ones" of Early Modern Europe

As Peter Burke noted in his survey of popular culture in "early modern Europe" between 1500 and 1800, "the small booksellers brought not real books in the modern sense, but 'little books,' that is, pamphlets, often only 32, 24, or even eight pages thick." They were printed in Spain and Italy as early as the early 16th century, and by the 18th century they could be found in most of Europe." [2] In the context of Western culture, "books" and "pamphlets" can never be equated.

The meaning of "book" is more serious and formal, generally referring to a formal cover, title page, catalog, back cover, a clear signature, and enough page numbers, rich enough content, the binding is very neat publication. Compared with the ancient medieval parchment books and ordinary paper books, "printed books" changed only the production technology, from handwriting to printing, but did not change the serious, formal form requirements, must pay attention to the quality of paper, ink grade, cover material, font and illustration design. Lewis Mumford pointed out that even after the invention of Gutenberg, "printed books" were treated mainly as "works of art" : "How precious and unique books are, and how much they are regarded as works of art, we can see from the rules passed down from generation to generation: Do not scribble in the blank!" No dirty finger marks on the book! There must be no corners in the pages! ' "Well into the 19th century, they would ask book decorators to retouch the printed pages: certain bright colors, ornate figures on the cover and intricate illustrations of flowers and geometric shapes, special initials at the beginning of paragraphs..." [3]

In contrast, the "booklet" not only has fewer page numbers, but also the paper quality, ink grade, cover material, art design, etc., are not particular. When UNESCO defined "pamphlet" in 1964, it was limited to "a small, loosely bound non-periodical publication" with a page number of "at least 5 and up to 48 pages excluding the cover", with more than 48 pages classified as a "book" [4]. Of course, in practical application, the number of pages in many brochures is not strictly limited to 32 pages or 48 pages, but to nearly 100 pages or even hundreds of pages. In short, as Peter Burke said, "pamphlets" are not "books in the true sense of the word."

As a form of written media, "pamphlets" existed before the invention of Gutenberg type, but they belong to the same category of "old media" as "handwritten books." From the perspective of historical semantics or etymology, the English word for pamphlet is Pamphlet, whose original etymology is the Latin pamphilus, which is composed of two roots: pam and phil. "pam" means "all, all," and "phil" means "love, affection," which together means "loved by all" or "loved by all." In the 12th century, a Latin love poem by Anonymous entitled "Pamphilus seu De Amore" (for All love), only three or five pages in length, circulated throughout Europe in the form of unbound loose-leaf, popular among the people of all countries, Middle English spelling "pamflet", The form later evolved into a pamphlet. Under the influence of the love poem, by about the end of the 14th century, all similar unbound or easily bound paper pages had been habitually collectively referred to as pamphlet, and its content was no longer confined to a love poem, but expanded to a wide range of subjects such as political insights and anecdotes [5]. After the invention of Gutenberg movable type printing, "pamphlets" and "books" together gradually transformed from "handwritten" production to "printed" production, thus forming two "new media" - "printed books" and "printed pamphlets".

Obviously, "printed pamphlets" are easier to popularize than "printed books," which are still regarded as "works of art." On the one hand, the "printed book culture" in the "first hundred years" has been slow to "leave a deep impression", on the other hand, far less than a hundred years, "printed pamphlets" just like its "beloved" name, soon "flourishing" : "Printing and cheap pamphlets already existed, and both had an unexpected boom with the Reformation." [6] In 1517, Martin Luther published his famous 95 Theses, which officially kicked off the Reformation. With the help of a publisher friend, Luther's Theses were printed and sold as pamphlets, "and in fourteen days the theses were all over Germany; Four weeks later, almost the entire Christian world was familiar with them. "[7] At this point, only 62 years had passed since 1455, when Gutenberg used his movable type to produce the first printed Bible.

Moreover, the "vigorous development" of the pamphlet was not limited to Germany, in addition to the Spain and Italy mentioned by Peter Burke, France, Britain and other countries were also involved. According to the famous French politician and historian Guizot in the 18th century, England during the bourgeois revolution was also "full of pamphlets" : "England in 1636 was full of pamphlets against the favor of the Catholics, against the chaos of the court, and especially against the dictatorship of Lauder and the bishops." The Star Court has severely punished the publication of such pamphlets more than once, but now there are more pamphlets than ever before, and they are so intense and so widely circulated that people are eager to read them first. These pamphlets were found in every town, even in the remotest villages, where daring smugglers made a fortune by bringing them in by the thousands from Holland; Commenting on the pamphlets in church." [8] Contemporary British scholar Joad Raymond has even argued that the "pamphlet" should be used as an important reference point for defining the mid-17th century in England: "The revolutionary years of the mid-17th century in England can be defined, to some extent, as the age of pamphlets or the widespread use of pamphlets in public debate." [9]

Pamphlet Empowerment: The reconstruction of Power structures in Early Modern Europe

According to the basic viewpoint of media environment school, media constitute the institutional and structural environment of human society and culture. In this environment, people are not only "mediated" to survive, but also "empowered" in a "mediated" way. The emergence of any new media means "empowerment and re-empowerment" [10]. For Europe in the early modern period, the "printed pamphlet", a new medium "loved by all", had a significant "empowerment" effect, which was concentrated in empowering various Reformed denominations, empowering the emerging bourgeoisie, empowering the ordinary people who had just begun to read.

The Reformation, which began in the early 16th century, was a profound adjustment of power structure in the early modern European society. On the one hand, it contributed to the collapse of the political and religious system dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, on the other hand, it laid the foundation of "Protestantism" - Lutheran, Calvinist and Anglican three "Protestant" denominations emerged one after another, and finally made the power structure of the whole Christianity show the "empowerment" of the "old Church" (Catholic) to "Protestant". During this period, in addition to oral public debate, the reformers' main medium was printed pamphlets. In the Middle Ages, the right to produce and enjoy parchment books and handwritten books was basically monopolized by the Holy See. Shortly after the invention of Gutenberg printing, printed books were still controlled by the elite class such as the church and the upper aristocracy in the form of "works of art" as mentioned above, and the supremacy of the church power was difficult to shake. The popularity of printed pamphlets provided a wide channel for religious reformers such as Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, John Calvin, and Menno Simens to speak. Of the approximately 498 printed pamphlets published in Germany in 1523, 180 were published by Martin Luther. [11] After 1530, the publication of classical works almost ceased; Few books are published; They were replaced by the mass publication of polemical pamphlets "[12]. In a way, without the full "empowerment" of printed pamphlets, it is likely that the Reformation would not have been successful, or at least much less effective.

Another very significant "empowerment" shift in early modern European society was the adjustment of the concept of rights from "feudal kingship" to "natural human rights". Along with the emergence of capitalist economy, the emerging bourgeois intellectuals, through the two ideological and cultural revolutions of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, finally dissolved the concept system of "divine right of Kings" and established the concept system of capitalist rights such as "separation of powers", "born free", "democracy" and "equality". In doing so, it was precisely because of the popularity of printed pamphlets that the late Renaissance reached the peak of the "pamphlet wars" : "The later stage of the development of humanism saw the contributions of many physicians, historians, and jurists who, in collaboration with scholarly printers, became advocates of the humanities." New departments were added to every graduate school, and there was a vigorous pamphlet war." [13] During the Enlightenment, although there was also the popularity of large printed books such as Diderot's Encyclopaedia, there were more flexible and inexpensive printed pamphlets. Voltaire, one of the most important leaders of the Enlightenment, used the pamphlet as his main tool of struggle: "A heavy 20-volume volume never initiates a revolution, but a thin pamphlet priced at 30 sous." [14] Obviously, behind the establishment of the various notions of rights of the new bourgeoisie, the printed pamphlet played an important "empowering" role.

In addition to the above two cases, printed pamphlets, as the "new media" that was "loved by everyone" at that time, also imperceptibly empowered ordinary people with basic reading ability - more full access to printed media. In Europe shortly after the invention of Gutenberg's movable type printing, the real "book" as a "work of art" was expensive and difficult to understand, and the general literacy rate in each country was not high - "In the European countries where printing was developed, the total population in the early years was definitely less than 100 million, of which only a minority were literate" [15]. So, as Peter Burke has found, for ordinary people who "read little" or "read more slowly and with difficulty," even if they have a strong desire to read, they have to face the question of affordability and "ability to read," and printed pamphlets are not only cheap, but "their language is usually very shallow and their vocabulary is relatively small." The syntactic structure is also very simple "[16]. It is clear that printed pamphlets provided ample "empowerment" for ordinary people in early modern Europe who were not economically well off but had a certain level of literacy and desired access to written media.

"Empowerment", as a "multi-level and broad conceptual system" that has gradually become popular since the 1960s and 1970s, focuses on empowering "vulnerable groups, marginalized groups or people with disabilities" in society [17]. The printed pamphlets of early modern Europe gave power to various reformed denominations, to the emerging bourgeoisie, and to the ordinary people who had just begun to read, which typically explained the purpose of the concept of "empowerment".

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

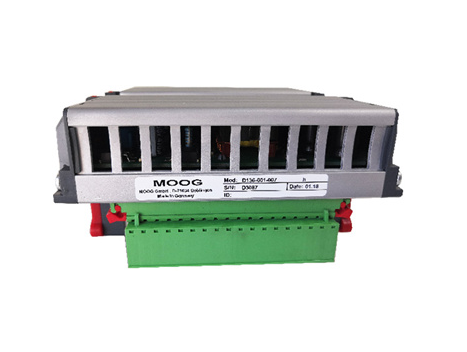

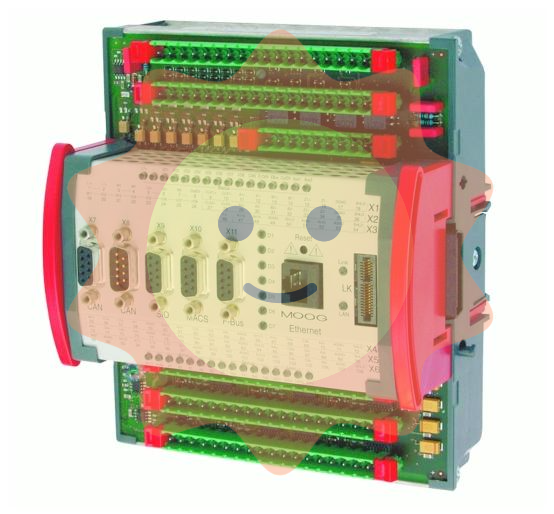

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

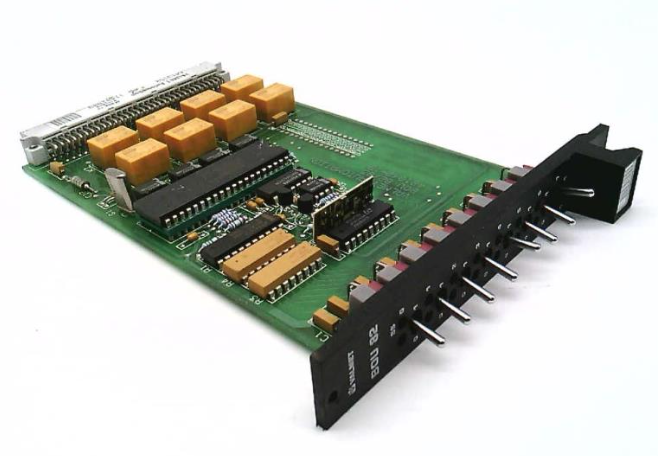

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

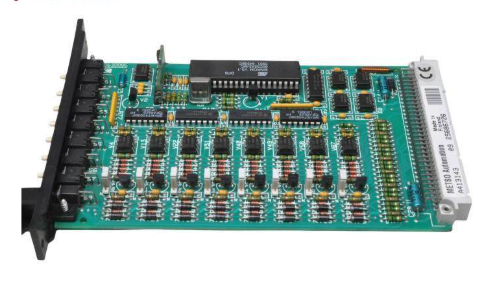

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands