Tracking the global Internet giants for more than a decade, perspective the real United States under the shadow of technology

In just over two decades, Amazon has risen to become the world's largest Internet company and the second largest private employer in the United States, with its "fulfillment centers" for warehousing and transportation spreading around the world and reshaping the way people live.

In a decade-long investigation, veteran US journalist Alec McGillis has witnessed how the company, once a symbol of technological progress, has grown into a capital monster that has defied the state. It brings the convenience of "one-click order", but also causes a series of chain reactions: the real economy continues to decline, and traditional communities have been withered; Squeezed by monopolies, small and medium-sized retailers are struggling; Workers are trapped in a high-pressure efficiency system and lose their dignity as workers.

Using Amazon as a lens, Alec McGillis captures people in the shadow of a tech oligarchy, showing an America divided geographically and classically by capital. Through a panoramic view, the book also shows that the upstream and downstream of the e-commerce industry, from industrial workers to ordinary buyers, are all caught in the slave trap of surveillance capitalism

We live in a time when we have everything, but we are trapped in a life of nothing; We get 30-minute takeout at the click of a button, next-day delivery of digital products, the convenience of seven-day returns for no reason, but lose the dignity of labor, the freedom of choice, the right to public participation, and the connections and human feelings that once existed in the neighborhood.

Hector Torres was asked by his wife to move into the basement. There's nothing wrong with him, let alone cheating in his marriage. He just didn't have the right job.

Ironically, if his wife hadn't pushed him, Hector wouldn't have taken the job. Hector was unemployed for 11 years when he lost his $170,000-a-year tech job during the Great Recession. More than 50 years old, was always favored young and energetic industry abandoned, people in the trough, Hector depressed, depressed. The family lives off the income his wife Laura earns from selling training courses on medical diagnostic equipment. In 2006, unable to afford a $5,500 monthly mortgage, Hector and his family fled the San Francisco Bay Area and moved to a larger house in suburban Denver, Colorado.

Then Laura gave her long-unemployed husband an ultimatum: If he couldn't find a job, he had to leave. So he returned to California to join his family. Hector comes from an immigrant family and came to California from Central America decades ago. His sister, who lives in the outer suburbs of San Francisco, took him in. If he plans to go out, he must be back before 8:30 p.m., otherwise he will disturb his brother-in-law's rest. The brother-in-law wakes up at 4:30 a.m. and drives to Silicon Valley before dawn, spending more than three hours a day commuting like 120,000 other Bay Area workers.

After five months of this, Laura found a way for her husband to return home, but he had to find a job. Hector did eventually find a job, but that was in June 2019, six months later. Once, he drove past a warehouse, saw a job Posting, stopped and asked, and they told him to report for work the next day.

Hector works four all-nighters a week, usually from 7:15 p.m. the night before to 7:15 a.m. the next. His rush around the warehouse -- loading out trailers, unloading them on pallets, sorting envelopes and packages -- meant that he spent the night standing at conveyor belts (there were no chairs in the warehouse), moving hundreds of items an hour from one belt to another, carefully positioned so that the side with the bar code faced up for scanning machines.

There was a huge pile of boxes waiting to be moved, some weighing as much as 50 pounds - weight was secondary, and the real problem was that until the boxes were lifted, it was impossible to tell whether they were light or heavy by their size alone. This unpredictable situation is a constant challenge for the body and mind. For a while, Hector wore a waist guard, but it was too hot to wear, like being roasted on a fire. He also developed tendinitis in his elbow. Each shift, he often walked more than 12 miles - according to the smart bracelet - he thought the bracelet must be broken, bought a new pedometer and wore it, and the reading was the same. Apply topical pain relief cream before work, take ibuprofen at work, stand on an ice pack when you get home, put a cold compress on your elbow, and soak your feet with Epsom salt. Shoes should be changed frequently to disperse the stress on the sole. Hector makes $15.60 an hour, a fifth of what he made when he was in the tech industry, and far better than being unemployed.

The warehouse, located in Thornton, 16 miles north of Denver, only opened in 2018. Clint Autry, the warehouse's general manager, has been with the company for seven years and has helped open many other facilities across the country. He has even been involved in testing radio-wave vests, "drive unit" robots in warehouses that move large loads and keep fully automated "colleagues" alert when workers have to step into their path. "Our key mission is to get products to customers in the fastest and most logistically cost-effective way," the general manager said during a presentation at a large open house at the Thornton Warehouse.

Since mid-March 2020, as COVID-19 containment measures have taken hold, the Thornton warehouse's total business has climbed, as has happened across the United States. Millions of Americans feel the only way to stay safe is to shop online from home, and orders are surging to holiday levels. Hector had only been on the job for nine months, and he was the only one of the 20 people who had gone through the orientation with him - the others either had trouble adjusting to the pace, suffered an injury, or ran out of time off after an injury and were laid off. Now, the pressure of a surge in orders, coupled with fears of close contact in warehouses amid the pandemic, is making the movement of people more frequent. The number of workers is shrinking, putting more pressure on those who remain. Hector was required to work overtime -- 12 hours a day, five days a week. With longer hours and fewer days off, Hector's tendinitis got worse.

He learned about the situation of the workers with whom he was in close contact and worked every day - the company did not say anything, but heard it from other workers. One day, the 40-something co-worker stopped showing up for work, and Hector thought he was one of those people who quit, because so many people just leave. But then it was said that the colleague had actually contracted the virus and was seriously ill. When Hector told his wife all this, Laura was worried about the health of her family, especially her elderly mother, who lived with them and suffered from a blocked lung. So Laura asked her husband to move into the basement. The basement wasn't much renovated, but they put a bed for Hector, equipped with a mini refrigerator, microwave, and coffee maker. To use the bathroom, he had to sneak upstairs.

What annoyed Laura was that they had all figured it out on their own, that the company had not informed Hector of anything. Nor did the company tell you how to deal with the risk of contagion. There is no public service hotline to consult. Laura tried looking online for instructions on how to deal with the situation, and the only thing she could find were the company's web pages boasting about what it had done as a company to cope with the coronavirus crisis. "They may have done a lot," she said, but the company "has profited off its employees every step of the way without giving them and their families the protections they deserve."

She could not help regretting that she had not rushed Hector to work there. "They call themselves a technology company, but they're really a sweatshop," Laura said. "This company controls our economy and our country."

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

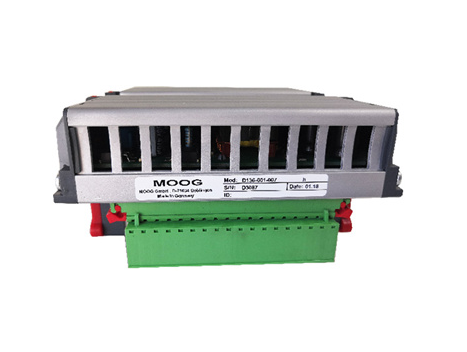

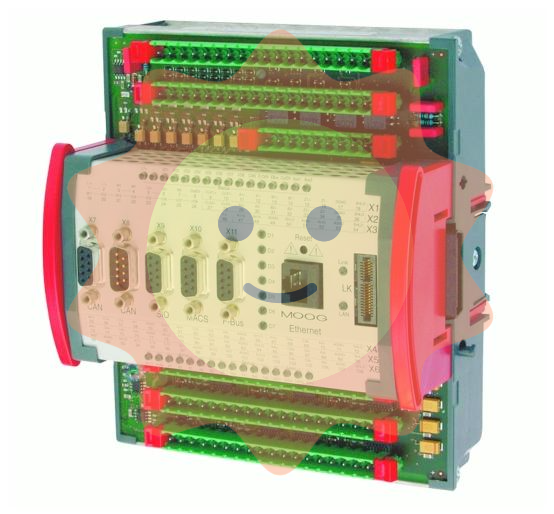

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands