In the face of the Internet world that has everything, why do people have nothing?

Some time ago, a university teacher experience delivery article in the network screen, although the content of the article is quite controversial, but it did succeed in triggering people's scrutiny of the delivery platform.

The scrutiny of Internet platforms is not a new topic, but an old topic on a global scale. While technology brings great convenience to human beings, it also triggers many dark sides. "The defining rule of economic development in the high-tech age will be summed up as follows: Winner takes all, and the rich get richer," wrote American author Alec McGillis in his book, "Keeping the Order: Everything and Nothing."

For those who run around under the algorithm system and always survive on the subsistence line, "winner takes all, the rich get richer" is indeed an insurmountable reality, and it is also a curse that cuts off the possibility of life.

Alec McGillis is a well-known American writer who has worked for a number of media outlets. He has spent more than a decade tracking the global Internet giant Amazon, exploring the collusion between technology and capital. In his view, understanding Amazon can identify many social problems in the United States: the rise of Amazon is accompanied by the tearing of American society, and the more accelerated the technology, the more the society will fall like dominoes; People seem to live in a time when they have everything, but they are trapped in a life of nothing; People can enjoy convenience such as food delivery and online shopping, but lose the dignity of work, freedom of choice and the right to public participation; The real economy continues to decline, traditional communities wither, and small and medium-sized retailers struggle... In the history of Internet companies, Amazon cannot be bypassed. In just over two decades, it has risen to become the world's largest Internet company, the second-largest private employer in the United States, and its "fulfillment centers" for warehousing and transportation have spread around the world, reshaping the way people live. Its rising road and operating model have become industry textbooks.

But at the same time, American society's scrutiny of Amazon has never stopped. In the shadow of the technological oligarchy, capital is tearing America apart along two dimensions: geography and class.

Of course, the valuable point of McGillis is that he did not just stay at the "experience" level, but deeply investigated the upstream and downstream of the entire industry, different enterprises and different types of work, avoiding the single direction of the conclusion, but also avoiding the practice of finding evidence after the conclusion. In his view, just blaming the problem on a single enterprise, in fact, will not help to improve and solve the problem. He acknowledges Amazon's brilliance as a business, but also points out Amazon's flaws, and more importantly, he does not believe that Amazon or even the Internet company is the fundamental problem that caused all this.

After the intervention of capital, the Internet has a greater voice than local governments

Since the birth of the Internet, freedom has been regarded as the core of the spirit of the Internet. However, the "convergence of capital and technology" that human beings have always faced since entering modern industrial society has also occurred in the Internet era. When capital intervenes, the Internet ecology changes.

Geographically speaking, people's emphasis on the freedom of the Internet in the past was often inseparable from the "freedom to choose where to live and work", believing that the space span of the Internet makes people have a broader space, and they can abandon cubicles and office parks. This is true for individuals, but it is also true for businesses.

Fulfilling the Order: Having Everything and Having Nothing.

But instead, McGillis writes in "Fulfilling the Bill," "Entrepreneurs in the tech industry are quickly discovering that location is more important than ever. The right location helps companies cluster with similar businesses, making it easier to attract employees-not only by poaching from companies across the street, but also by having a reputation as an industry hub that attracts new talent. When you lose your current job, it makes sense to go to a place where you can get another decent job nearby. As a result, people are willing to work in industry centers, which in turn attracts more employers. Agglomeration is not only a matter of human resources, it is also important to innovate the essence of this technology. In a sense, it's always true: History is the story of the right cities and the right people coming together to move the world forward."

This agglomeration has certainly provided convenience for companies and job seekers, and has become the capital of local governments to show off, but it has also intensified the class division, and the cost of living has been greatly increased even at the higher levels of the class.

The paper points to Seattle as an example of this result: the city has added 220,000 jobs in the decade since 2008, and more than 20 Fortune 500 companies have decided to set up engineering or R&D operations there, including Facebook, Google and Apple. Per capita income in the Seattle metro area has grown to nearly $75,000 in 2018, about 25 percent higher than cities like Milwaukee, Cleveland and Pittsburgh, which were at the same level a few decades ago.

On the other hand, Seattle's wealth growth has been unevenly distributed. Seattle was a famous middle-class paradise with few extreme poor and few extreme rich. But by 2016, income inequality in Seattle was already extremely high, with fewer than one in five families having children because of the difficulty of raising a family and rising rates of childbearing. Even so, the urban population continues to grow faster than any large city in the country, and the vast majority of the new population is young, highly educated and well-paid.

Amazon is Seattle's most powerful tech company. Amazon has 45,000 jobs in the city alone, and another 8,000 in the suburbs. It occupies one-fifth of the office space in Seattle, as much space as the next 40 largest companies combined.

However, such a huge enterprise is far less than the head of the traditional manufacturing industry in terms of income. Workers at GM factories once made an average of $27 an hour with generous benefits, but a decade later, Amazon was paying workers at the same location $12 or $13 an hour with even thinner benefits.

In 2018, the median home sale price in Seattle reached $754,000, enough to cover the cost of the median salary of $134,000, while Amazon's average annual salary is $150,000. Raising a family in Seattle is also a bit of a stretch for Amazon employees.

But even that hasn't stopped local and state governments from offering Amazon up to $43 million in incentives to open warehouses here. Across the United States, Amazon has won tax breaks and incentives from states and cities in exchange for building warehouses and data centers, earning a total of $2.7 billion in 2019 alone.

As the main clue of the book, "Amazon fulfillment center" is actually just a business term. "In this large enclosed building, workers and robots pick goods from shelves, which are then packed and shipped by workers," the book says. The company calls such a first-level warehouse a "fulfillment center." After all, they are the place to fulfill and fulfill customer orders. In addition, there are smaller and relatively few 'sorting centers' that sort packages that have been assembled and addressed for distribution within a specific area. But the word Fulfillment, plastered in large black letters next to the company's name, seems designed to conjecture something broader than the building's function. It advertises the company's promise to everyone who walks by, and those who want to buy something but are still on the sidelines now know where it will be delivered to them."

But for the people who work in this building, there is not much promise from the owner. They have to deal with hard work and the fact that they are struggling to survive in an increasingly expensive city. At the same time, whether to have such enterprises is also the key point of local economic growth. The rise and fall of American cities in recent decades is precisely the pattern of the decline of old industrial cities and the rise of new technology cities. In other words, head technology companies such as Amazon have eliminated the geographical distance of this era through the Internet and even the new industries derived from it, but it has aggravated the economic differences between regions, and also exacerbated the wealth disparity in the same region.

As a company, Amazon has profoundly influenced the social ecology of the United States. "In the United States, more people subscribe to its Prime service than voted for Trump or Biden in past elections." Fully half of Americans' online spending takes place on Amazon. It is the second largest private workplace in the United States, after Walmart, employing more than 800,000 people, most of whom will never set foot within the factory confines of its Seattle headquarters."

The economic ecology that Amazon relies on is not just the rise of Internet technology. In the late 1970s, federal rules governing corporate mergers were loosened, antitrust enforcement weakened, and the flow of wealth to a small number of companies became a trend. With the help of this trend, Internet companies began to profoundly dominate the economy and life.

Amazon's power has made local governments eager. According to the book, just to attract Amazon's second headquarters to land, local governments have launched a "fancy show."

In 2017. Amazon is considering choosing cities to build its second headquarters, and many cities are trying their best to fall into their own hands. The mayor of a city has given a thousand Amazon products five-star online reviews, a city has offered to cater to Amazon's love of dogs by waiving local pet adoption fees for Amazon employees, a city has offered to add Amazon-only cars to its subway system, and a city has even offered to simply change its name to "Amazon City."

Of course, for Amazon, which has a strong capital power, all this looks like a farce, and it is impossible to impress it. Declining industrial cities did not make the cut, nor did ordinary inland cities, which preferred high-talent cities on the coast or cities near the nation's capital - the final choices were the Long Island City neighborhood in New York and the Crystal City area in Arlington, Virginia, near Washington. Of course, later due to various reasons, the former was also abandoned.

Amazon doesn't care about the city's overtures because it has more power than the city. The power of this capital has brought commercial prosperity and new economic model, but it has affected the social ecology.

The recession of the real economy, the plight of small and medium-sized retailers is obvious, "for every job created, Amazon will lay off two independent retailer employees," but this is only the first step. Due to the change of commercial ecology, the community space formed by commercial inertia in the past decades has also withered, and people no longer care about the life within a few hundred meters. The giant beast of capital forces the city to transfer various rights in order to "attract investment", which in turn infringes the rights of the people and brings the double loss of public space and public discourse right. The various tax exemptions and tax breaks obtained by Amazon have greatly reduced the city's finances, which in turn affect the public construction and social welfare system.

The widening divide between cities is even more troubling because of the peculiarities of the tech economy, as McGillis puts it: "The rich rewards depend on innovation itself, which can generate disproportionate returns with very little additional capital." Once you design a brilliant new piece of software, you can mass-produce it at almost zero cost - no coal, no iron ore. It all depends on having the mind to make the original breakthrough... The feedback loop is so pervasive that the market rebalancing mechanism dispersed to low-cost regions is broken."

In the years after 2008, employment in big cities grew almost twice as fast as in smaller cities, and incomes grew 50% faster. The collective urban boom of the past in the United States is gone. Almost all the rich cities are on the coast, and more than 70% of venture capital goes to California, New York and Massachusetts. "Performing the Bill" analyzes the adverse impact of urban wealth disparity: "The first is the political cost. Voters in lagging districts are resentful, drawn to opportunistic candidates and cynical television outlets, and vulnerable to racists and nativists. Rather than deterring racism and xenophobia, the recession has armed them. In the American political system, which distributes power not just on the basis of population but on the basis of region, this resentment plays a big part, especially in the Senate. As the region declines and hollows out, the regions left behind have accumulated enormous influence and want to express their pain. But the damage doesn't end there. Regional inequalities make it impossible for one part of the country and another part of the country to understand each other."

Fulfillment Center: Witness the overload of labor force

For cities, competing for Amazon means future economic growth; for ordinary people, enjoying Amazon shopping is a convenience of life; for Amazon white-collar employees, Amazon brings them decent jobs and income, although rising housing prices often outweigh income growth. But for those at the bottom, many things are not pretty.

Amazon now has more than 110 fulfillment centers across the country, with warehouses within 25 miles of about half the U.S. population and in nearly every state, allowing it to deliver about half of its orders itself.

But at the same time, it's the hard work of the employees. Night staff at the center work only four days a week, but must work continuously for 12 hours from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., with only a 20-minute break in between. Wear a wristband that records your movements and sends a vibration warning shortly after you leave your workspace. Moving hundreds of items an hour, with the side with the bar code facing up, some items can weigh as much as 22 kilograms and each shift has to travel 19 kilometers.

And that job is being replaced by robots. Amazon has already deployed 200,000 robots around the world to pick and move goods.

Amazon also leases 60 planes and contracts with cargo airlines to use them more frequently, forcing pilots to work 18-hour days as a result. In February 2019, a plane contracted by Amazon crashed near Houston, killing all three people on board.

Amazon also has a fleet of 20,000 diesel vans and 7,500 trailers, and is preparing to order 100,000 electric vans for drivers. But in terms of their labor contracts, the drivers, while delivering exclusively for Amazon, are actually working for contractors. This outsourcing mechanism allows drivers not to enjoy any of Amazon's employee benefits, and in the event of an accident, Amazon can escape responsibility. "In one shift, a driver needs to complete up to 150 deliveries, and they handle 1,000 packages per week. UPS uses high-tech facilities to train drivers and guides them through virtual reality obstacle courses to avoid hazards; In contrast, many of Amazon's drivers don't have access to additional training resources beyond watching instructional videos on their phones."

The number of accidents at the fulfillment Center is also very high, and the serious injury reporting rate is more than twice the national average for the warehousing industry. In 2017, in Illinois, a 57-year-old man named Jollier died of a heart attack because he did not get medical attention in time. His wife later claimed in a lawsuit that warehouse supervisors waited 25 minutes after the accident to call emergency services and also let emergency workers walk through the huge warehouse instead of allowing them access from the loading and unloading area near Jollier's location. The boxes of automated external defibrillators scattered around the warehouse were empty, according to the lawsuit. A year and a half later, a 61-year-old worker died of a heart attack at a warehouse in Murfreesboro, Tenn., when a two-way radio used to signal emergency care failed to work properly.

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

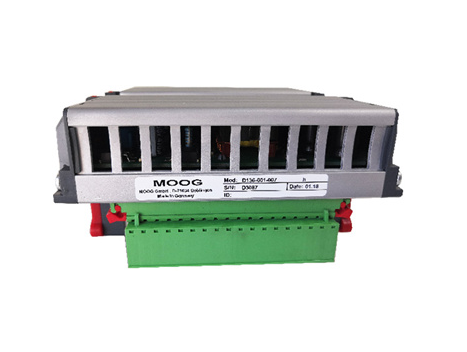

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands