Recent developments in nanomaterials in personal care products

01 Preamble

Personal care products - such as cleaners, moisturizers, deodorants, and sunscreens - are ubiquitous in modern life. Nanomaterials are increasingly being used in personal care products to improve product efficacy. For example, silver nanoparticles have anti-fungal and anti-bacterial properties, which are well suited for some efficacy skin care products and shampoos. Between 2012 and 2017, Nanodatabase (maintained by DTU Environment, the Danish Ecology Council and the Danish Consumer Council) increased its catalog of nanoproducts from 407 to 1,089, an increase of nearly 168%. This growth in nanomaterials requires consideration of the potential safety impact of these additives on consumers.

In this review, we first examined the existing literature on exposure, toxicity, and sustainability of nanoparticle additives. Then we look at US regulations and guidelines on how to deal with commercial applications of nanomaterials.

02 Dew

To gain insight into the types of nanomaterials contained in personal care products reaching consumers, we first analyzed online inventories of three types of nanomaterials. We compared the number of nano personal care products in the Consumer Product Catalog (CPI) to the number in the Nanodatabase and Skin Deep Cosmetics databases. Product catalogs in CPI and Nanodatabase search for "Health and Fitness," "Personal Care Products," "Cosmetics," and "Sunscreens," respectively. We then narrowed the search results to TiO2, ZnO, and Ag.

As of June 27, 2018, both CPI and Nanodatabase show that Ag is the most prevalent of the three nanomaterials (found in 158 products). ZnO is the least popular, being found in 29 products in CPI and 30 products in Nanodatabase. However, Skin Deep Cosmetics showed TiO2 to be the most common, with titanium dioxide found in nearly 97 percent of nano personal care products, while Ag was the least common.

The difference between Skin Deep Cosmetics versus CPI and Nanodatabase can be partially optimized by relevant search parameters. Skin Deep Cosmetics is specialized in classifying chemical products such as oils, waxes, creams, liquids, foams and powders. In contrast, CPI and Nanodatabase's "personal care products" category also includes non-chemical products such as straighteners, hair dryers, and combs. The Ag-enabled products cataloged in CPI and Nanodatabase contain a large number of such tools. After excluding the "personal care products" category in the CPI or "suspended in liquids" containing Ag, TiO2 became the most common nanomaterial.

By comparing the products containing TiO2, ZnO and Ag, the Skin Deep Cosmetics database is still different from the CPI and Nanodatabase, especially the latter two Ag is twice the former. In addition, while CPI and Nanodatabase indicate that Ag is the most widely used nanomaterial in personal care products, Piccinno et al report that the average annual production of TiO2(3,000 mt/year) and ZnO(550 mt/year) exceeds that of Ag(55 mt/year) worldwide.

According to the proportion of TiO2, ZnO and Ag, it is estimated that the proportion of cosmetics is 70-80%, 70% and 20% respectively. The output of cosmetics is shown in Table 2. The estimated yields of these three nanomaterials are TiO2 > ZnO > Ag, corresponding to the ranking in the Skin Deep Cosmetics database. Keller et al. estimate that the use of nanomaterials in cosmetics accounted for 16% of the global engineered nanomaterials in 2010.

Although the CPI and Nanodatabase information is not completely correct, we continue to use both databases because some products in the CPI are not found in Nanodatabase. We searched the "Health and Fitness" category and keywords such as "Cosmetics", "Personal Care" or "Sunscreen", and found a total of 981 personal care products in Nanodatabase, whose nanomaterial distribution is shown in Figure 1. Ag-containing products include soaps, sprays, and topical creams because Ag has good antibacterial properties. TiO2 and ZnO have been widely used in sunscreen emulsions because of their potential to absorb a broad spectrum of ultraviolet rays.

We also adjusted the position of nanomaterials in cosmetics through the classification structure reported in the literature. As shown in Figure 2, the majority of nanomaterialized products surveyed are used in products that can be suspended (57% of products), or attached to the surface of the product (36% of products). We observed that most products with surface-bound or solidly dispersed nanomaterials are tools, such as straighteners, hair dryers, and combs. Table 3 shows the data of TiO2, ZnO and Ag.

Product exposure scenarios vary depending on product type, nanomaterial type, and exposure pathway. Figure 3 and Table 4 show the results of the search after exposed path optimization. Based on the intended use of these products by consumers, we estimate that 90% of personal care products are made through contact on the skin, 6% through inhalation, and 4% through ingestion.

Most nano personal care products are creams, shampoos and other chemicals applied directly to the skin. The inhalation and ingestion risks of TiO2, ZnO and Ag are mainly through the types of products such as sunscreen powders, spray products and lip balms. Although most products are applied to the surface of the skin, these products can be indirectly inhaled or ingested during and/or after application to the skin. And that includes a potential eye exposure risk.

The available data on nanomaterials exposure in personal care products is not comprehensive. Because manufacturers are not legally required to disclose the amount of nanomaterials used in personal care products, we cannot estimate individual consumers' exposure to nanomaterials based on personal care product sales alone. A growing number of modelling studies assess consumer exposure to nanomaterials in consumer products, including cosmetics such as sunscreen, toothpaste or shampoo, and consumer products for children.

However, product-specific testing is required to verify that the estimates made using these models are correct. In the United States, the literature on nanoscale personal care products lacks standardized exposure models and comprehensive nanomaterial exposure data collection. Because the FDA does not require premarket exposure testing for nanomaterials, manufacturers are left to their own devices to confirm or deny the presence of nanomaterials in personal care products.

As a result, consumers do not have access to the data until the product is released. There are only limited, retrospective exposure analyses conducted by independent academic researchers who also attempt to characterize nanomaterials contained in personal care products. For example, Botta et al. studied four commercially available sunscreens and reported using ICP-AES to determine the percentage of TiO2 by weight from 3.72% to 5.33%. The concentration of additional products of nanoparticles reported in the literature is shown in Table 5. The data from these limited selection of consumer products justify the need for further research on personal care product exposure as a first step in regulation.

Recent studies on skin exposure have focused on sunscreens and moisturizers containing TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles. The recommended amount of UV protection for the skin is approximately 4 oz/day, which corresponds to local exposure to approximately 60 g or 3.8 mg/cm2 of TiO2 and/or ZnO per day. However, skin contact is not limited to skin care products, but also includes casual skin contact with aerosols.

For example, using the ConsExpo and ECETOC TRA models, skin exposure after a single application of the nano-cleaning spray is estimated at 0.0106-1.43 mg/kg. However, the degree of dermal absorption reported in the literature varies, with some studies claiming that nanoparticles penetrate the skin barrier into the bloodstream, while others claim that nanoparticles are only present in the stratum corneum. To date, there is little evidence that nanomaterials can penetrate dermis under natural environmental conditions.

In some cases, those nanomaterials that can be used for dermal absorption show greater penetration of the epidermis, such as those found in wound dressings and anti-aging creams. After 4 to 6 days of use of silver-containing wound dressings, the scanning electron microscope (SEM) can observe silver clusters in the reticular dermis. Using icp to measure dry tissue, the total amount of Ag transferred to the skin was detected to be 40.1 μg /g (range 6-199μg /g).

Assuming a tissue mass of 150 mg and a bandage containing 4% Ag, the maximum amount of Ag measured by the skin species is 30µg. In another study, Ag nanoparticles were only found in the stratum corneum after human skin was exposed to textiles containing Ag nanoparticles for five consecutive days, which was inferred to be due to particle aggregation. The results show that the variation of Ag nanoparticles in the release depends on the incorporation method and wetting conditions of Ag.

Research into inhalation exposure of nano personal care products such as cosmetic powders and sprays has received a lot of attention. These results indicate that: (a) a small amount of nanomaterials are usually released during normal use of these products; (b) Released nanoparticles typically exhibit altered composition, shape and size due to interactions with other components; (c) The health effects of these interactions are still largely unknown. It is estimated that a person using a cleaning product containing nanomaterials at one time may inhale 3.3× 10-6.75 ×10-2 mg/m3.

For aerosol products containing Ag nanoparticles, Quadros and Marr estimate that 0.62 ng of Ag is inhaled after 20 sprays, which corresponds to an aerosol concentration range of 1.6× 10-7-3.7 ×10-5 mg/m3.

For nanopowder, the highest aerosol concentration measured in a controlled laboratory simulation was 3.4×104 units /cm3 at 14.1 nm. Depending on size, respiration rate, type of respiration (nose or mouth), and pre-existing lung conditions, aerosolized aggregates and pure nanomaterials appear to deposit. Smaller aerosols may penetrate deep into the respiratory tract, with 10-20nm sized aerosols deposited in the alveolar region.

The oral and ocular pathways of exposure appear to be the least studied. Oral exposure to nanomaterials in cosmetics may occur primarily with direct use of products such as toothpaste, mouthwash, or throat sprays. Dutch Romperberg et al. estimated that young children may consume 2.16μg TiO2/kg per day from food, supplements, and toothpaste. Using a toothbrush containing Ag nanoparticles may also lead to oral administration of silver nanoparticles. The literature reports that about 10 ng Ag is released in the form of 1-3% particles over 4 months, which is considered insignificant. Accidental ingestion can also accidentally transfer, by touching the hand to the mouth, by draining into the throat after inhalation, or by draining into the nasal cavity after eye exposure.

To fully understand potential consumer risks, exposure studies must be considered in parallel with toxicity studies. Exposure helps estimate the dose of nanomaterials that a human organ might receive under real conditions. Common challenges in exposure assessment arise from the dynamic shape, size, and aggregation of nanoparticles with other cosmetic ingredients. In order to meet the requirements of experimental data, some exposure models of nanomaterials need to be established. These models include the Stoffenmanager Nano model (qualitative exposure estimation), NanoSafer and ConsExpo nano models (quantitative exposure estimation).

However, according to the European Regulation on Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) in the European Union, current exposure models cannot be compared with experimental measurements because they cannot account for this dynamic aggregation/aggregation and shape change.

There is a long-standing debate about what specific measures might be required for a thorough exposure assessment. For large particles, particle mass measurements are useful, but nanomaterials contribute little to the mass relative to rough materials. Nor can particle mass explain the structural and functional properties of nanomaterials. The researchers suggest a combination of measurement methods to more accurately assess the exposure of nanomaterials - suggested measurement characteristics include shape, surface area, surface chemistry, surface charge, size, chemical composition, crystal structure, porosity, and agglomeration state. REACH also extensively lists the nano-specific data required for a comprehensive exposure assessment of nanomaterials.

03 Toxicity

Consumer exposure to personal care products mainly occurs at the product use stage and is associated with the greatest risk of exposure to nanomaterials. Toxicity assessment using in vitro and in vivo tests usually follows recommended guidelines set by international organizations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Although data in vitro and in animals provide valuable predictions of the extent of harm and potential mechanisms of action, these studies are not always correct for predicting biological effects in humans. Since human data for Ag, TiO2, and ZnO nanoparticles are available, we will focus on reviewing toxicological data from human exposure studies.

Human skin exposure data for the presence of Ag, TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles in textiles and sunscreen products. Studies using wound dressings and textiles containing Ag nanoparticles have shown no change in serum Ag levels and no discomfort or histopathological changes in the skin after about a week of direct contact. For physical sunscreens, the active ingredient is usually a mixture of TiO2 and ZnO.

In a study by Tan et al., volunteers applied a sunscreen containing 8%TiO2 twice daily for 9-31 days. No obvious trauma, rash or adverse reactions were observed. Skin exposed to titanium concentrations (0-4 µg/g) and control tissues (0-2 µg/g), no correlation was found between exposure duration and concentration. When the sunscreen combined with TiO2 nanoparticles and ZnO nanoparticles penetrated the epidermis with a higher concentration of zinc (1.25 -- 2.66µmol/ g) than titanium, titanium was not detected.

Two studies by Gulson et al. examined the efficiency of zinc absorption in the skin by using the stable isotope Zn68, which contains a relatively low natural abundance. Fourteen healthy volunteers were treated with a dose containing 4.3 mg/cm2

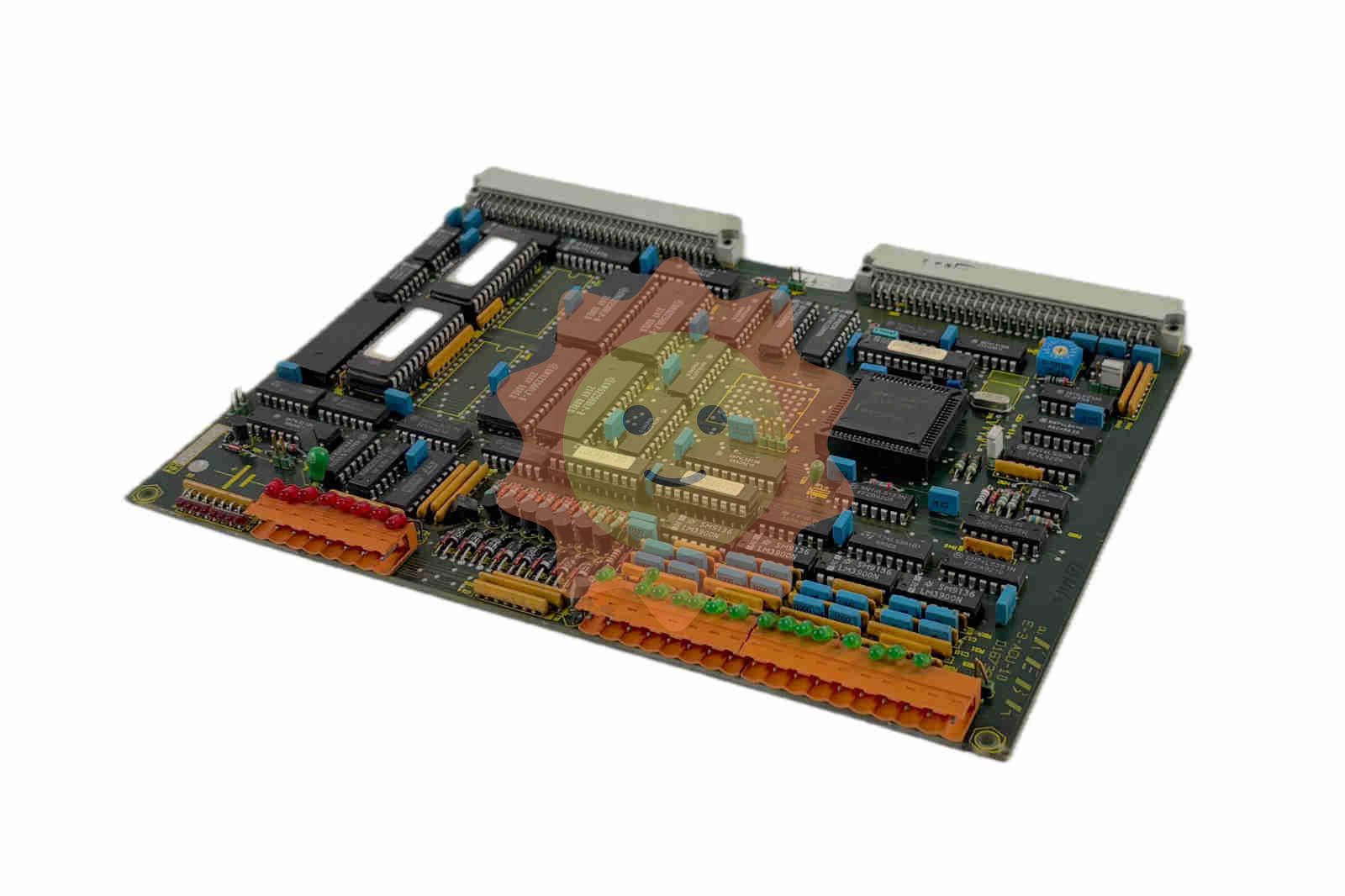

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands