The depth of the last round of ship cycle

A look at the historical cycle of ships: How should we view the rise of ships in the early 21st century

When we noticed the wave of container ship orders starting in the second half of 2020, the ship market, which has been quiet for a decade, seemed to stir up a wave. Although more than a decade from 2008 to 2020 will indirectly appear in 2014, 2015 short-lived container ship orders, but the trend is short, and failed to form a strong support for ship prices. The wave of container ship orders beginning in the second half of 2020, however, is significantly better than any time in the past 10 years from the perspective of downstream freight rates or new shipbuilding contract prices. In our last big topic, "Ship Industry Topic: Ten years of the night of the ship market fading, thousands of sails to the sun", it is clear that the mainstream ship type represented by bulk carriers and oil tankers will be significantly higher in the next ten years. So, how we look at the specific direction, twists and turns and height of this round of ship cycle, this issue will be of great practical significance. In this report, we will give an in-depth review of the last great ship cycle (2002~2008).

1. The ship cycle that is getting narrower, but the drop is getting higher and higher

Maritime Economics has made statistics on the trend and duration of ship cycles in the past hundred years, and from this review, we can see that since the 20th century, ship cycles seem to be becoming narrower and narrower, and the gap is getting higher and higher. This is partly due to the rapid development of global economy and global trade and technological changes in the shipping field after the 20th century, but also due to the shift of the center of gravity of global trade and shipbuilding several times after the 20th century (before the 20th century, the Victorian era, Europe almost completely assumed the center of global trade, The rise of manufacturing in North America and East Asia and resource exports from South America and Australia after the 21st century have weakened Europe's trade position.

If we take a slightly shorter view and focus only on the global ship market after the 1970s, we will find three distinct upward and downward periods from the perspective of global new ship prices. The first is from 1976 to 1980, benefiting from the rapid development of Japanese economy and the improvement of global trade environment, global ship prices rose rapidly; Then, from 1981 to 1985, the capitalist countries faced the oil crisis, fell into stagflation, and global trade declined; Then, from 1986 to 1991, despite the lack of actual incremental demand, shipowners began placing orders after the oil crisis, taking into account the rise of large tankers and the need for replacement tankers (at that time, there was a certain miscalculation that the average working life of tankers was 20 years and the global oil voyage distance was likely to increase significantly). However, in the context of relatively weak demand, supply soon overflowed, and fell into a 10-year adjustment period after 1991. Although there was a short-term market for bulk carriers from 1994 to 1995, ship prices still tended to weaken. After 2002, the trauma caused by the United States "911" incident to the global investment confidence is being repaired, and the ship market has also climbed rapidly with China's accession to the WTO, ushering in the historical golden period of the ship market, and hit a record high in terms of order volume and ship price. Another point of concern is that we categorize the drivers of the three upward cycles, among which the first (1976~1980) and the third (2002~2008) upward stages are typical new demand drivers, typical features are the rapid growth of fleet ownership, mass delivery of ships, and shortage of shipyard capacity; The second stage (1987-1992) was typically driven by renewal demand, characterized by high ship delivery and dismantling volume, slow growth in global fleet ownership, and relatively smooth decline in ship prices from the peak of the cycle.

In order to better distinguish between the upcycle driven by new demand and the upcycle driven by replacement demand from a "volume" point of view, we also show the delivery volume of the sub-class from 1960 to 2007. It can be seen that in the two new demand-driven upward cycles, ship delivery increased year by year; However, in the upward cycle driven by replacement demand from 1987 to 1992, its delivery growth was not obvious. On the other hand, before 1987, the volume of ship dismantling reached its peak, so it also better illustrates the upward cycle driven by replacement demand, which is only a one-way force on the supply side, and the global fleet size has not increased significantly, and the height that can be achieved is relatively limited.

If we make a qualitative assessment of the supply and demand conditions of the ship market and the market prosperity of the ship market after 1869, when the trend of the cycle is obviously up and down (excluding World War I and World War II), we find some patterns: 1) The rapid growth of demand does not necessarily lead to market prosperity, nor does the rapid expansion of production capacity necessarily mean market prosperity, only the need for rapid growth and continuous shortage of production capacity can bring market prosperity; 2) A neutral market is usually a transitional stage with a high probability of prosperity or decline; 3) When there is obvious excess capacity or a significant decline in demand, the market will inevitably weaken; 4) The core point is that demand growth may not necessarily be cyclical, but the state of production capacity will lag to adapt to demand and have a more direct link with the market boom.

2. Overview of "volume and price" of ship market from 2002 to 2008

Now let's focus on what happened to the global shipping market from 2002 to 2008 in the last upward cycle. The indicators we track are still new build prices and new ship orders for each type of vessel segment.

Next, we look at orders for new ships. The trend of this index also has several stages like the price of new shipbuilding: 1. From 2002 to 2003, the number of new ship orders rose rapidly, and oil tankers and container ships were the main driving force of growth; 2. From 2003 to 2005, the number of new ship orders declined, and the main ship types that declined were oil tankers, container ships and bulk carriers. 3. From 2005 to 2007, the number of new ship orders rose rapidly, and the main thrust in 2006 and 2007 were oil tankers and bulk carriers respectively. By 2007, global orders for new ships in terms of deadweight tonnage exceeded 20 billion DWT, a 160% increase from 2005.

To sum up, the volume and price of the last round of ship cycle is the general trend, but the process is not smooth sailing, but there are twists and turns. In addition, the performance of different ship types varies greatly over different time periods. This makes us question: As a very classic ship upward cycle, why are the economic performance of various types of subdivided ships different in different time periods? What are the common reasons that make each type of ship have their own boom period from 2002 to 2008? In the next chapter, we will focus on the analysis of the "personality reasons of subdivided ship types" and "market commonality reasons" that contributed to the continuous upward trend of ship market popularity from 2002 to 2008.

Second, get to the bottom of the matter: analysis of the reasons for contributing to the last big cycle

1. The personality reasons of each subdivision ship type

Major ship types include oil tankers, bulk carriers and container ships. Different from the upswing cycle that mostly relied on the support of oil tankers from 1956 to 1973, the ship upswing period from 2002 to 2008 can be described as "a hundred flowers blooming", and all types of mainstream ship types have ushered in volume and price growth, but the growth pace is different. We reviewed the tanker, container and bulk carrier markets in turn and explored their respective growth logic.

1) Tankers: Double hull tankers replace single hull tankers, contributing to the growth of thrust in the early stage

It can be seen from the distribution of new orders signed by each subdivision ship type that the main driving force of the ship market in 2002~2003 was from oil tankers. The early growth demand for oil tankers did not come from the new demand: 1) First of all, although the global oil price began to accelerate after the 21st century, the overall increase was still not obvious from 2000 to 2003, and the demand for downstream shipping enterprises to expand capacity was not sufficient; 2) We compared the age distribution of each vessel type in 2003 and 2004, and found that the proportion of older tankers older than 20 years in the fleet decreased rapidly, which indicates that a large proportion of older tankers were withdrawn from the market in 2003, so the large number of orders generated in the year met the replacement demand in nature.

In fact, there was a general expectation in the shipping market that a large number of single-hull tankers built in the 1970s would be withdrawn from the shipping market by 2010, and the proportion of elimination accounted for a high proportion of the fleet at that time. The reason why these old single-hull tankers have to be withdrawn from the market is due to the new shipping regulations of IACS and IMO. One of the biggest impacts on tankers is the Common Structural Practice (CSR), which comes from the International Maritime Organization's concern about the environmental pollution risk caused by oil spills from single-hull tankers. By the end of 2004, among tankers with more than 5,000 deadweight tonnage, double-hulled tankers accounted for 65% of the total tonnage and 56% of the total number of ships, and the proportion of elimination is still very large.

Global oil prices began to rise rapidly after 2004, and a large number of old tankers were dismantled from 2002 to 2005 (according to ISL, a total of 17.42 million deadweight tons were dismantled in two years, accounting for 71% of all ships dismantled), and CSR will come into effect on April 1, 2006. As a result, a large number of ship owners placed orders first, and these three factors together led to the rise of the tanker market again in 2006, and the new tanker orders signed in the first half of 2006 reached 46.5 million deadweight tons, more than the total number of orders received in 2005. By the end of October 2006, tanker orders accounted for 124% of single-hull tanker ownership, far more than 79% at the beginning of the year. By 2008, it can be seen from the age statistics of various types of oil tankers divided into single and double hulls, except for the VLCC still maintaining a large number of single hulls in the age segment of 10 to 14 years, the double hulling process of the rest of the deadweight tonnage of oil tankers has achieved great progress.

2) Container ships: The containerization rate continues to increase, and the global trade environment improves

Unlike bulk carriers and tankers, which mainly carry commodities, the container ship market is more dependent on the global trade environment for manufactured goods or consumer goods, and therefore more related to the increase in global trade, especially the increase in commodity trade. In fact, the process of trade globalization has accelerated since the 1950s, and the share of global trade in global GDP has risen from 24% in 1960 to 60.7% in 2008. The proportion of commodity trade in global GDP also rose from 16.7% in 1960 to 51% in 2008, which can be said that this 50 years is the historical golden period of container ship development, but also let container ships officially enter the mainstream ship ranks. From 2002 to 2007, the global container seaborne trade volume increased from the initial 73.01 million TEU to 142.9 million TEU in 2007, with a compound annual growth rate of 14.4%.

On the other hand, the proportion of global commodity trade using container transport is also gradually increasing. In the 1970s, container ships began to enter the global trading fleet in large numbers, and in the 21st century, the pace of containerization has accelerated significantly, and the ratio of tonnage of container fleets and grocery fleets in various countries has gradually increased. In 1970, the deadweight of the world's container fleet was 1.908 million tons, which was 1/38 of the deadweight tonnage of general cargo ships. By 1994, this ratio had risen to 1/2.65, and by 2002, this ratio had risen to 1/1.26. Show more obvious "growth". Considering the late start of the development of container ships themselves, although the increment of container ships in the last big cycle was relatively stable, due to the small base, so as of July 2007, container ships were the ship type with the largest proportion of orders in the total shipping capacity (the ratio was higher than that of oil tankers and bulk carriers).

Combining the factors in the above two paragraphs, we understand that the individual factors that led to the rise of container ships in the last cycle are mainly the continuous improvement of global commodity trade and the improvement of containerization rate. In fact, at the beginning of the 21st century, the trend of larger container ships began to be particularly obvious, and this in the background of gradually improving demand, but also gave shipowners the power to replace large container ships. Although the trend of ship upsizing has been intensifying since the 1980s (except for oil tankers), container ships are the ones that have really made steady progress in upsizing since the 21st century. This is mainly due to the high concentration of container ships' routes and the fixed consumption costs of container ships (fuel and port charges are fixed due to the periodic characteristics of consolidated transport). Therefore, the upsizing of ships has a great effect on cost reduction and efficiency increase. According to the China Shipbuilding Industry Yearbook, in 2008, the proportion of ships in the existing container fleet greater than 8,000 boxes was only 30%, and in 2015, the proportion increased to 80%. The above shows that the incentive for shipowners to replace large container ships is particularly strong, and in the last round of ship upward cycle, container ships have both the demand gain of "improving global commodity trade" + "increasing containerization rate" and the supply drive of "improving the capacity of shipyards to build large container ships".

3) Bulk carriers: structural changes in supply and demand led to high freight rates, and the rise of orders in 2006 and 2007

Finally we look at the bulk carrier. If before 2007, whether it is new orders or hand-held orders, oil tankers are the largest proportion of ship types, then 2007 is the "first year" when bulk carriers significantly exceed oil tankers, and up to now, bulk carriers still occupy the largest proportion of the total fleet size. From 2002 to 2005, the volume of newly signed bulk carriers has been stable, between 10 million and 30 million deadweight tonnage, and in 2006, 2007 began to increase greatly, only in the first half of 2007, the volume of newly signed bulk carriers was as high as 77.8 million deadweight tons. Corresponding to the order volume of new ships is the shipping price of bulk carriers. We review the BDI (Baltic Dry Index) and BDTI (Baltic Crude Oil Freight Index) and find that the historical volatility of BDI is significantly stronger than that of BDTI. The reason is that BDI often represents the demand for industrial raw materials in international trade, and its demand curve is rigid, that is, once it breaks through the capacity carrying range, the expansion of demand will bring unlimited price amplification. From the perspective of bulk freight rates, BDI achieved breakthrough growth from 2005 to 2007, the highest rise to more than 10,000 points, which makes dry bulk trade become particularly profitable, and bulk carrier orders are also in 2006, 2007, accompanied by a lot of speculation, passed to the shipyard.

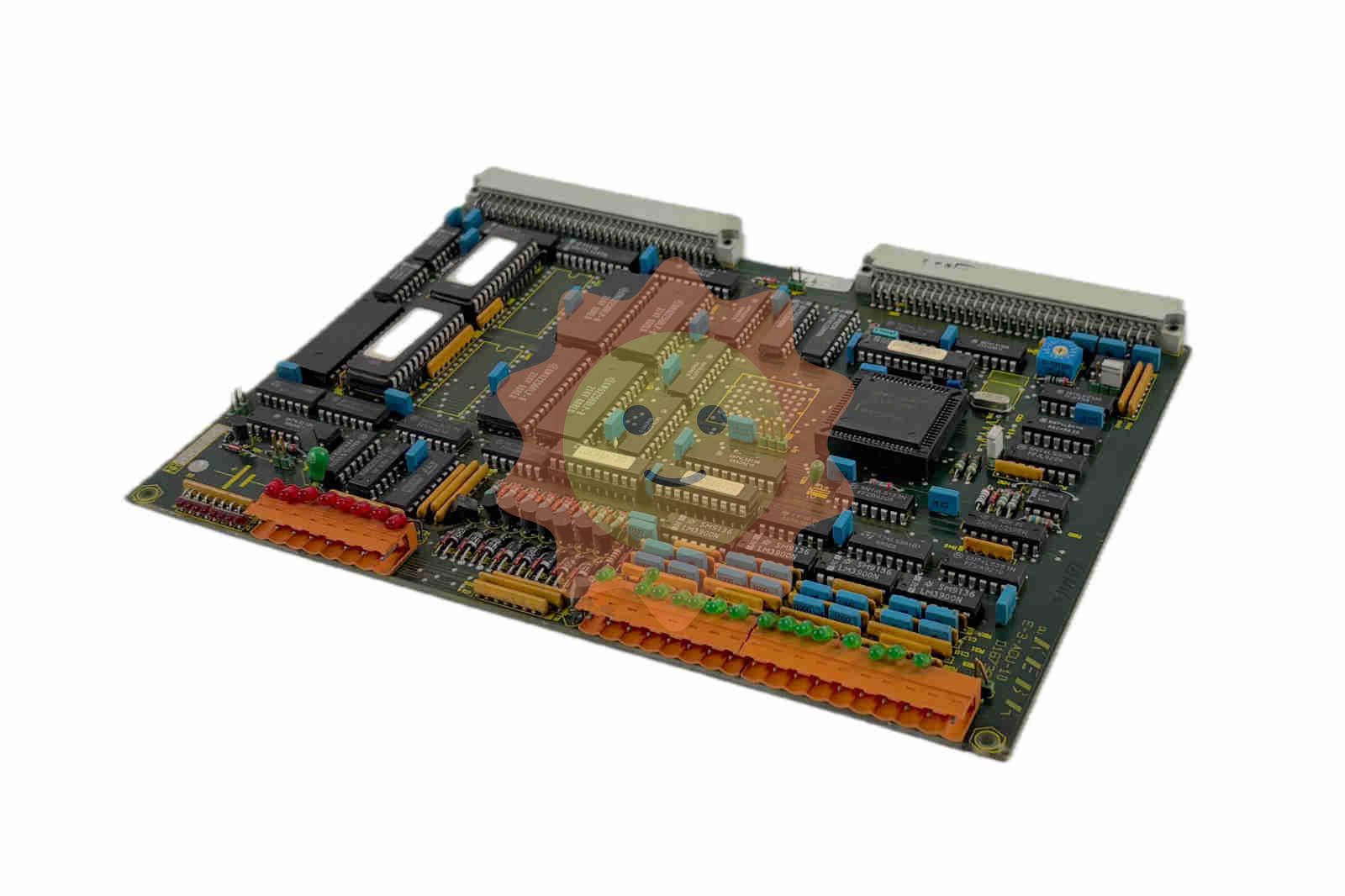

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands