Forerunner of the forgotten era of "printing civilization"

The forerunner of the "printing civilization" era of "Gutenberg's bright stars" is not the "book" that we are familiar with, but a kind of media that is almost forgotten today - "printed pamphlets". In the "early modern period of Europe" between 1500 and 1800, this "printed pamphlet" was not only "everywhere" but also "loved by everyone," and had a remarkable "empowering" effect: empowering the various Reformed denominations, empowering the emerging bourgeoisie, empowering the ordinary people who were beginning to read. At the same time, it plays an irreplaceable "empowering" effect on the advanced development of the whole European society: in the political aspect, it lays a tradition of political participation supported by "freedom of publication"; in the economic aspect, it opens a media economy model with "cheap orientation" as the basic strategy; in the cultural aspect, it reveals a path of cultural prosperity with "media fusion" as the important concept.

According to McLuhan's definition, the invention of Gutenberg movable type printing has epoch-making significance - constructing a "printing civilization" era of "Gutenberg's bright stars" for human beings. But Elizabeth Eisenstein, also a representative scholar of the media environment school, found a very interesting historical detail that is extremely worthy of consideration: "The book culture produced in the first hundred years after the invention of printing is not much different from the hand-written book culture of the past." The closer you look at the early machine prints of this period, the less likely you are to be impressed by the changes brought about by printing." [1] In other words, the so-called "Gutenberg star bright" is not immediately "dominant" performance.

What, then, was the "explicit" sign of the arrival of a printed civilization? It was a large-scale "pamphlet" publication.

"Flying" printed pamphlets: The "Loved ones" of Early Modern Europe

As Peter Burke noted in his survey of popular culture in "early modern Europe" between 1500 and 1800, "the small booksellers brought not real books in the modern sense, but 'little books,' that is, pamphlets, often only 32, 24, or even eight pages thick." They were printed in Spain and Italy as early as the early 16th century, and by the 18th century they could be found in most of Europe." [2] In the context of Western culture, "books" and "pamphlets" can never be equated.

The meaning of "book" is more serious and formal, generally referring to a formal cover, title page, catalog, back cover, a clear signature, and enough page numbers, rich enough content, the binding is very neat publication. Compared with the ancient medieval parchment books and ordinary paper books, "printed books" changed only the production technology, from handwriting to printing, but did not change the serious, formal form requirements, must pay attention to the quality of paper, ink grade, cover material, font and illustration design. Lewis Mumford pointed out that even after the invention of Gutenberg, "printed books" were treated mainly as "works of art" : "How precious and unique books are, and how much they are regarded as works of art, we can see from the rules passed down from generation to generation: Do not scribble in the blank!" No dirty finger marks on the book! There must be no corners in the pages! ' "Well into the 19th century, they would ask book decorators to retouch the printed pages: certain bright colors, ornate figures on the cover and intricate illustrations of flowers and geometric shapes, special initials at the beginning of paragraphs..." [3]

In contrast, the "booklet" not only has fewer page numbers, but also the paper quality, ink grade, cover material, art design, etc., are not particular. When UNESCO defined "pamphlet" in 1964, it was limited to "a small, loosely bound non-periodical publication" with a page number of "at least 5 and up to 48 pages excluding the cover", with more than 48 pages classified as a "book" [4]. Of course, in practical application, the number of pages in many brochures is not strictly limited to 32 pages or 48 pages, but to nearly 100 pages or even hundreds of pages. In short, as Peter Burke said, "pamphlets" are not "books in the true sense of the word."

As a form of written media, "pamphlets" existed before the invention of Gutenberg type, but they belong to the same category of "old media" as "handwritten books." From the perspective of historical semantics or etymology, the English word for pamphlet is Pamphlet, whose original etymology is the Latin pamphilus, which is composed of two roots: pam and phil. "pam" means "all, all," and "phil" means "love, affection," which together means "loved by all" or "loved by all." In the 12th century, a Latin love poem by Anonymous entitled "Pamphilus seu De Amore" (for All love), only three or five pages in length, circulated throughout Europe in the form of unbound loose-leaf, popular among the people of all countries, Middle English spelling "pamflet", The form later evolved into a pamphlet. Under the influence of the love poem, by about the end of the 14th century, all similar unbound or easily bound paper pages had been habitually collectively referred to as pamphlet, and its content was no longer confined to a love poem, but expanded to a wide range of subjects such as political insights and anecdotes [5]. After the invention of Gutenberg movable type printing, "pamphlets" and "books" together gradually transformed from "handwritten" production to "printed" production, thus forming two "new media" - "printed books" and "printed pamphlets".

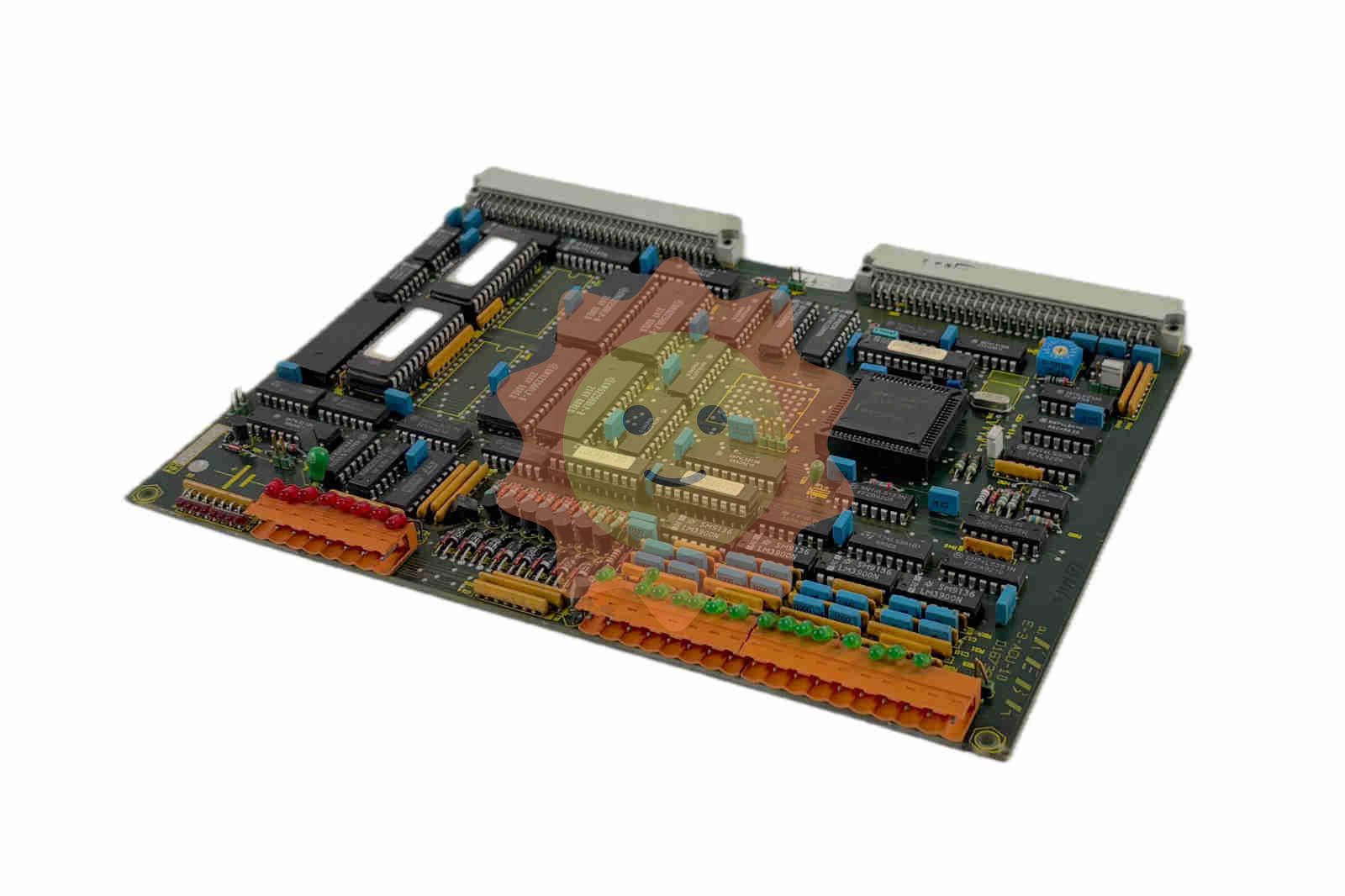

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands