Why and how to treat municipal sewage?

In the context of a growing world population and increasing urbanization, the provision of drinking water and sanitation remains a critical issue for many cities, particularly in developing countries. Sanitation is an umbrella term for all technologies used to collect, transport and treat wastewater before it can be discharged into the natural environment. It can be planned at the scale of an urban area (i.e., a centralized sanitation facility) or conceived at the scale of a residential dwelling, i.e., not connected to a centralized sewer network (i.e., a stand-alone sanitation facility). There is a tendency for future wastewater treatment plants to become true wastewater treatment plants, where green energy, fertilizers and precious metals can be produced and treated wastewater can be reused.

1. Brief history of urban health

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Maxima Sewer

Figure 1. Maxima Sewer in Rome, by Agostino Tofanelli (1833).

The earliest drainage systems were built in ancient times, such as the famous Maxima sewer in ancient Rome (Figure 1). After the fall of the Roman Empire, the drainage system was gradually abandoned. Sewage, feces, and other waste are discharged directly, causing foul odor, well water contamination, and many diseases.

Following the cholera epidemic that followed in the 19th century, the sanitary movement of the 1850s advocated the construction of underground drainage systems (Figure 2) to drain sewage, stormwater, and street water directly into rivers or oceans. As a result, the length of the sewage network in the city of Paris increased from 150 km in 1853 to nearly 900 km in 1890 (currently about 2,500 km). A law enacted in 1894 forced buildings in Paris to discharge their waste, rainwater, and black water [1] into a newly constructed (so-called combined) drainage system. [2] The concept of a sewage system was born.

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Paris Sewers

Figure 2. A photograph of the Paris sewers taken by Nadar in 1861. [Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]

It was not until the 1960s that new urban areas and new cities began to build separate drainage systems to collect and treat domestic sewage and rainwater, respectively. Waste water generated by polluting industrial activities cannot be discharged directly into the sewage system and must be treated by the industry itself. In view of the diversity and particularity of the nature of pollutants and treatment processes, this article will not discuss the case of industrial wastewater.

Sewage discharges move the pollution problem outside the city, causing increasing pollution of surface water. The earliest sewage purification technology appeared in the 1860s, spraying sewage on sandy soil to take advantage of the soil's purification power while increasing agricultural and commercial vegetable production.

With the increasing urbanization and the increasing amount of sewage collected, the area of land used for sewage purification also increased (up to 5,000 hectares in Paris around 1900). Sewage purification capacity also increased slowly between 1870 and 1900, thanks to the removal of solids from sewage before spraying by means of precipitation, chemical treatment, or anaerobic fermentation (i.e. in the absence of oxygen).

In the 1880s, artificial filters with high porosity made of materials such as coke, bottom ash, and volcanic ash appeared, which promoted the great development of biofilm [3] purification reactors (biofilters). These reactors are a breeding ground for bacteria. The first biofilm purification reactor was built in Salford (UK) in 1893.

In 1914, British researchers Arden and Lockett found that pollution control was much faster when already-grown purifying organisms were added to untreated sewage. [4] They filed the first patent for the purification process, known as the activated sludge process. The process does not use a filter, but is based on the cultivation of purified organisms (activated sludge) suspended in water to a great extent. The process was first engineered in 1914 in the United Kingdom in the form of a single reactor (sequential batch influent), followed by a continuous influent bioreactor connected to a sedimentation tank (or clarifier) in 1916.

Thanks to advances in electromechanical equipment and the accumulation of scientific knowledge since the 1970s in understanding and optimizing reactions to eliminate nitrogen and phosphorus pollution (denitrification and phosphorus removal), these processes continue to improve to this day. Although many biofilters and activated sludge process wastewater plants were built as early as the 1920s and 1960s, it was not until the 1970s that the construction of wastewater treatment plants in developed countries really began to accelerate, supported by a growing collective sense of environmental protection and increasingly stringent regulations (read the French Water Code).

2. Why treat municipal sewage?

2.1 Composition of urban sewage

Municipal sewage contains a large number of organic and inorganic compounds derived from black water (containing urine and feces), dirty water discharged from kitchens, laundry rooms and bathrooms, and surface runoff. For ease of analysis and regulation, a composite index (expressed in mg/l) that includes multiple contaminants is commonly used to characterize untreated and treated wastewater:

The content of suspended matter (SM), which represents particulate matter that can be trapped by a 2µm aperture filter membrane. They are made up of about 25 percent minerals and 75 percent organic matter called volatile substances. Volatile suspended solids are an important component of COD.

Chemical oxygen demand (COD) is the amount of oxygen required to completely oxidize dissolved and granular organic pollution, including biodegradable COD and non-biodegradable COD two parts. This complete oxidation is done in a very acidic environment by using a very strong oxidizing agent (potassium dichromate) and reacting for 2 hours at a temperature of about 150°C [5]. For untreated domestic sewage, about 50% of COD is dissolved and the other 50% is granular.

Five-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) is the amount of oxygen consumed by bacteria as they degrade the biodegradable organic matter in them over a period of five days. The high COD/BOD5 ratio (2 to 5) of municipal wastewater indicates that organic pollutants can be easily removed biologically in wastewater treatment plants.

Kjeldahl nitrogen [6] (NK) is organic nitrogen (including urea, amino acids, proteins...) And ammonia nitrogen (N-NH3).

Total nitrogen (NGL) is the sum of organic nitrogen, ammonia nitrogen, nitrite nitrogen, and nitrite nitrogen. Neither of the latter two forms of nitrogen is present in untreated municipal sewage.

Total phosphorus (Pt) includes organic phosphorus and inorganic phosphorus.

Table 1 shows the average water quality characteristics of municipal sewage at the entrance of the sewage treatment plant and the minimum water quality requirements (maximum allowable concentration or minimum treatment efficiency) of treated sewage as required by regulations.

Table 1. Average composition of untreated municipal sewage and example of discharge standards for large wastewater treatment plants (over 100,000 inhabitants).

Municipal sewage also contains many inorganic and organic compounds in very low concentrations (from a few ng/l to a few µg/l). The main types of micropollutants are cosmetics, pesticide and insecticide residues, solvents, natural and synthetic hormones, drug residues, metals, etc. Such micropollution is the subject of a campaign to control the discharge of hazardous substances to the environment. At present, there is particular concern about the concentration levels of pesticide residues, drugs and endocrine disruptors in the inlet and outlet water of sewage treatment plants.

Municipal sewage also contains high concentrations of fecal microorganisms, especially pathogenic microorganisms, the number and type of which depends on the health status of the population.

2.2 Impact of discharge on water environment

Untreated municipal sewage discharged into surface water can cause visual pollution (floaters), reduce the transparency of the water, and contribute to the siltation of lakes and rivers. The discharge of biodegradable substances will enhance the microbial activity in the water body, resulting in a decrease in the concentration of dissolved oxygen, and even cause other organisms in the water body to suffocate due to lack of oxygen. Nitrogen and phosphorus emissions can lead to eutrophication in water bodies (read Phosphorus and Eutrophication and Nitrates in the Environment).

The discharge of micropollutants can have toxic effects on plants and animals in the water environment. These effects include bioaccumulation of persistent molecules in the food chain, chronic toxicity from very low doses, and changes in endocrine system function that can lead to consequences such as feminization of male fish. Microbial contamination of water can render the water unfit for certain uses.

2.3. Obligations for wastewater treatment

Microorganisms naturally present in surface water can degrade pollutants caused by sewage discharge, but the self-purification capacity of rivers is generally very inadequate. Therefore, sewage must be treated in a treatment plant before being discharged into the natural environment. For the various composite pollution indicators, the maximum allowable concentration of treated sewage must not be exceeded or the minimum purification efficiency stipulated by the provisions of the regulations should be achieved, as shown in Table 1 (see also the French Water Code).

3. How to treat wastewater?

Environmental Encyclopedia - Sewage - Activated sludge floc

Figure 3. Microscopic observation of activated sludge floc (400 times magnification). In the view are a nematode and a rotifer.

Municipal wastewater is mainly treated by biological methods and is combined with liquid/solid separation processes (precipitation, filtration, air flotation) to remove suspended solids and retain the resulting biological matter. The biological material that acts as a purification is basically composed of bacteria (primary producers) that have the property of secreting extracellular polymers [7] and can form settling floc [8] or biofilm in which other microorganisms (protozoa, metazoa) are also constantly multiplying as predators 。

Biological reactions to remove organic matter, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution all require special operating conditions (presence or absence of dissolved oxygen, residence time of biomass in the reactor, etc.). The removal of these contaminants or the purification of the water is accomplished by the cultivation of biological matter suspended in the water or attached to the filler.

3.1. Biological transformation of pollution

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Organic pollution transformation process

Figure 4. Conversion process of organic contamination in the presence of dissolved oxygen or nitrate ions in the bioreactor. [©Joseph De Laat]

Biodegradable organic matter (consisting of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates) is used as food by microorganisms called heterotrophic bacteria because they use organic carbon as a source of carbon for their development and reproduction (anabolic) and for their energy requirements (catabolism) (Figure 4). The production of new cells also requires the participation of ammonia nitrogen and phosphate, and their concentrations in untreated sewage can greatly meet the demand. In the presence of dissolved oxygen or nitrates, organic matter in sewage is converted to carbon dioxide and biological matter in roughly equal proportions.

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Nitrogen pollution transformation process

FIG. 5. Transformation pathways of nitrogen pollution in wastewater treatment plants. [©Joseph De Laat]

The main conversion reactions of nitrogen pollution in wastewater treatment plants are ammoniation, assimilation, nitrification and denitrification

Ammoniation (reaction 1) converts organic nitrogen (mainly contained in sewage urea) to ammonia nitrogen. This reaction is quick; Many types of microbes can perform this reaction:

Urea [CO(NH2)2]→ Ammonia [NH3]+ Carbon dioxide [CO2]

Assimilation (reaction 2) is when ammonia nitrogen is assimilated by bacteria to form new organic nitrogen biomolecules for the synthesis of new bacteria.

Biological nitrification (reactions 4a and 4b) converts ammonia nitrogen (ammonium, NH4+) to nitrite nitrogen (nitrite, NO2 -) by aminooxidating bacteria, which then converts it to nitrate nitrogen (nitrate, NO3 -) by nitrifying bacteria:

Ammonium [NH4+]→ Nitrite [NO2 -]→ nitrate [NO3 -]

These reactions occur only under aerobic conditions and are carried out by microorganisms called autotrophic bacteria because they use inorganic carbon (CO2 or HCO3 -) as a carbon source to synthesize new bacteria.

Biological denitrification (reaction 5) reduces the nitrate ion (NO3 -) to nitrogen (N2). In sewage treatment plants, denitrification can only occur in the absence of oxygen. Denitrification is done by heterotrophic bacteria and requires the consumption of organic matter. Take methanol (a small organic molecule that is easily biodegradable) as an organic matter in the denitrification process, which is accompanied by the elimination of organic pollution (being oxidized to CO2) :

Nitrate [NO3 -]+ methanol [CH3OH]→ Nitrogen [N2]+ Water [H2O]+ carbon dioxide [CO2]

As with the removal of ammonia nitrogen, the growth of biomass during nitrification is accompanied by the partial removal of phosphorus through assimilation (synthesis of phosphorus into new biomolecules).

In order to further biological phosphorus removal, it is necessary to alternate the biological material through anaerobic and aerobic stages, resulting in the formation of phosphorus-removing bacteria called phosphorus-accumulating bacteria, which have the property of excessive accumulation of phosphorus in their cells. Phosphorus can account for 10%-12% of the dry weight of phosphorus removing bacteria, while the proportion of phosphorus in the dry weight of non-phosphorus removing bacteria is 1%-2%.

In wastewater treatment plants, biological phosphorus removal only removes about 40-60% of phosphorus. In order to meet the discharge standards (see Table 1), it is also necessary to supplement physical and chemical phosphorus removal, that is, to add iron salt (usually ferric chloride, FeCl3) by forming iron phosphate precipitation removal.

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

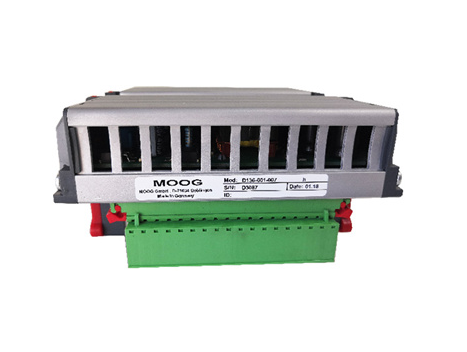

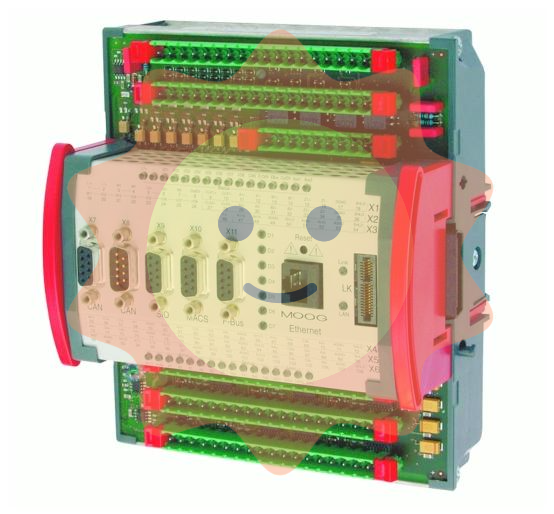

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands