Why and how to treat municipal sewage?

In the context of a growing world population and increasing urbanization, the provision of drinking water and sanitation remains a critical issue for many cities, particularly in developing countries. Sanitation is an umbrella term for all technologies used to collect, transport and treat wastewater before it can be discharged into the natural environment. It can be planned at the scale of an urban area (i.e., a centralized sanitation facility) or conceived at the scale of a residential dwelling, i.e., not connected to a centralized sewer network (i.e., a stand-alone sanitation facility). There is a tendency for future wastewater treatment plants to become true wastewater treatment plants, where green energy, fertilizers and precious metals can be produced and treated wastewater can be reused.

1. Brief history of urban health

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Maxima Sewer

Figure 1. Maxima Sewer in Rome, by Agostino Tofanelli (1833).

The earliest drainage systems were built in ancient times, such as the famous Maxima sewer in ancient Rome (Figure 1). After the fall of the Roman Empire, the drainage system was gradually abandoned. Sewage, feces, and other waste are discharged directly, causing foul odor, well water contamination, and many diseases.

Following the cholera epidemic that followed in the 19th century, the sanitary movement of the 1850s advocated the construction of underground drainage systems (Figure 2) to drain sewage, stormwater, and street water directly into rivers or oceans. As a result, the length of the sewage network in the city of Paris increased from 150 km in 1853 to nearly 900 km in 1890 (currently about 2,500 km). A law enacted in 1894 forced buildings in Paris to discharge their waste, rainwater, and black water [1] into a newly constructed (so-called combined) drainage system. [2] The concept of a sewage system was born.

Encyclopedia of the Environment - Sewage - Paris Sewers

Figure 2. A photograph of the Paris sewers taken by Nadar in 1861. [Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]

It was not until the 1960s that new urban areas and new cities began to build separate drainage systems to collect and treat domestic sewage and rainwater, respectively. Waste water generated by polluting industrial activities cannot be discharged directly into the sewage system and must be treated by the industry itself. In view of the diversity and particularity of the nature of pollutants and treatment processes, this article will not discuss the case of industrial wastewater.

Sewage discharges move the pollution problem outside the city, causing increasing pollution of surface water. The earliest sewage purification technology appeared in the 1860s, spraying sewage on sandy soil to take advantage of the soil's purification power while increasing agricultural and commercial vegetable production.

With the increasing urbanization and the increasing amount of sewage collected, the area of land used for sewage purification also increased (up to 5,000 hectares in Paris around 1900). Sewage purification capacity also increased slowly between 1870 and 1900, thanks to the removal of solids from sewage before spraying by means of precipitation, chemical treatment, or anaerobic fermentation (i.e. in the absence of oxygen).

In the 1880s, artificial filters with high porosity made of materials such as coke, bottom ash, and volcanic ash appeared, which promoted the great development of biofilm [3] purification reactors (biofilters). These reactors are a breeding ground for bacteria. The first biofilm purification reactor was built in Salford (UK) in 1893.

In 1914, British researchers Arden and Lockett found that pollution control was much faster when already-grown purifying organisms were added to untreated sewage. [4] They filed the first patent for the purification process, known as the activated sludge process. The process does not use a filter, but is based on the cultivation of purified organisms (activated sludge) suspended in water to a great extent. The process was first engineered in 1914 in the United Kingdom in the form of a single reactor (sequential batch influent), followed by a continuous influent bioreactor connected to a sedimentation tank (or clarifier) in 1916.

Thanks to advances in electromechanical equipment and the accumulation of scientific knowledge since the 1970s in understanding and optimizing reactions to eliminate nitrogen and phosphorus pollution (denitrification and phosphorus removal), these processes continue to improve to this day. Although many biofilters and activated sludge process wastewater plants were built as early as the 1920s and 1960s, it was not until the 1970s that the construction of wastewater treatment plants in developed countries really began to accelerate, supported by a growing collective sense of environmental protection and increasingly stringent regulations (read the French Water Code).

2. Why treat municipal sewage?

2.1 Composition of urban sewage

Municipal sewage contains a large number of organic and inorganic compounds derived from black water (containing urine and feces), dirty water discharged from kitchens, laundry rooms and bathrooms, and surface runoff. For ease of analysis and regulation, a composite index (expressed in mg/l) that includes multiple contaminants is commonly used to characterize untreated and treated wastewater:

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

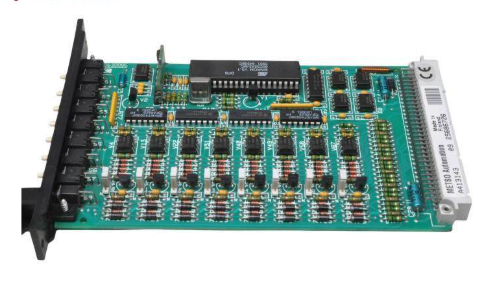

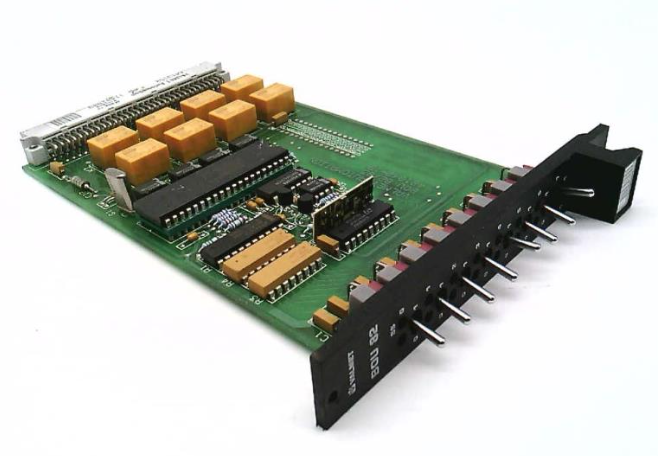

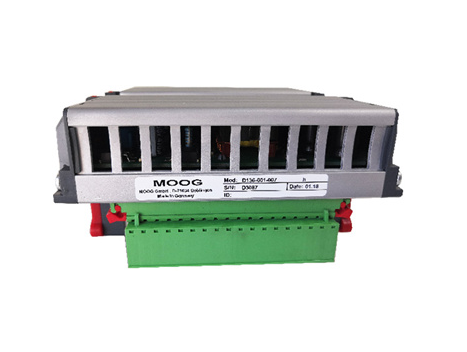

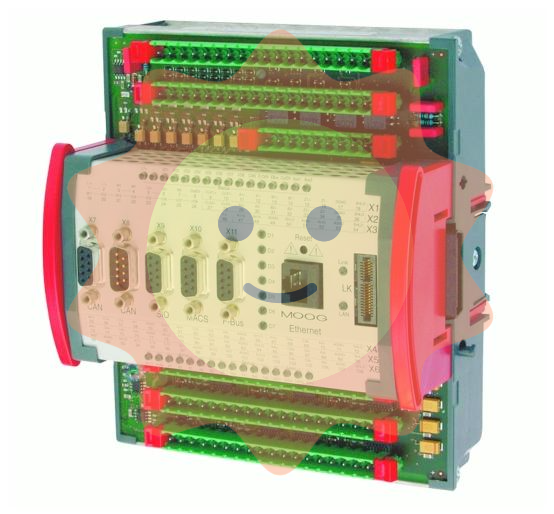

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands