Future chemical technology development guide

Chemistry has a long history of creating many important high-quality products and processes, but it has also brought problems. For sustainable development, what characteristics and production processes of chemical products will society need in the future? It's worth thinking about.

World science

Based on the frontiers of world science; Focus on global science and technology hot topics; Tracking the stories behind scientific discoveries; Provide a stage for the collision of academic ideas.

In January 2020, Professor Julie B. Zimmerman, Associate Director of the Yale Center for Green Chemistry and Green Engineering; Paul T. Anastas, the father of green chemistry; and Hanno C. Rekpor, associate professor at Yale University. Erythropel and Walter Leitner, former editor-in-chief of the journal green chemistry, published their co-authored review, "Designing for a green chemistry future," in Science.

At the beginning of 2020, this digital year that seems to have a transformational significance for mankind, with the title of "Blueprint for the future of Green chemistry", profoundly describes the ideas and suggestions for the sustainable development of green chemistry, and puts forward the twelve principles of green chemistry, which have to be said to have profound meaning.

-- Professor Jiang Xuefeng of East China Normal University

In a sustainable society, the material base depends to a large extent on chemical products and their production processes, which are designed according to the principle of "good for people's lives". The inherent properties of molecules can be considered from the earliest stage (i.e. the design stage) to solve problems such as repeatability, risk and stability of products and processes. The chemical products, raw materials and manufacturing processes of the future need to integrate green chemistry and green engineering into the concept of sustainable development. This transformation requires advanced technology and innovation, as well as systems thinking and system design that starts at the micro molecular level and has a positive impact on a global scale.

When designing for the planet of the future, the scientific question facing the field of chemistry is no longer whether chemical products are necessary, but what characteristics and processes of chemical products are required for a sustainable society?

Chemistry has a long history of creating many important high quality products and processes. The current chemical industry is a production chain that relies on raw materials, which are mainly limited fossil resources in nature. These reactants are often highly reactive and toxic, often resulting in accidental leakage, resulting in poisoning of workers (such as the methyl isocyanate leak in Bhopal, India; Dioxins have leaked in Times Beach, Missouri, USA, and Seveso, Italy).

At the same time, most manufacturing processes produce an even higher proportion of waste (often toxic, persistent, and bioaccumulative) than expected products, especially when product complexity increases (e.g., specialty chemicals produce 5 to 50 times more waste than expected products, and pharmaceuticals 25 to 100 times more).

Target chemical products are often designed for their intended use to control the production environment to reduce the potential hazards of spills, and these hazards are often not assessed, possibly due to the lack of appropriate tools and models for a long time, as evidenced by numerous accidents.

Since chemical products continue to provide many conveniences to society, the design of chemical products in the future must contain two objectives:

One is how to maintain and improve performance,

The second is how to limit or eliminate harmful effects that threaten the sustainable development of human society.

Answering these questions is a serious scientific challenge.

A large number of scientific achievements in the field of green chemistry and green engineering show that chemical products and production processes can reduce the adverse impact on human society while realizing more functions. These successes are not hearsay, but need to be achieved through a systematic system of thinking.

In order to achieve this goal, it is necessary to change not only the conditions and environment in which chemical products are produced and used, but also the inherent characteristics of chemical products and reagents themselves along the entire value chain, from raw materials to applications. This requires shifting the definition of "performance" from "function" to "function and sustainability," a goal that can only be achieved by grasping the intrinsic properties of molecules and their variations and designing them.

Design and innovation should be carried out in a comprehensive system framework

It is very challenging to pursue sustainable design improvements in complex systems using traditional simplification methods.

In the chemical industry, although the reductionist focus only on function can extend the life of chemical products to a certain extent, it may still exist in water after the end of life and be exposed to unprotected people.

Agrochemicals, which increase crop yields but lead to fish kills and groundwater degradation;

Chemicals make materials last, but they also accumulate in our bodies and in our biological chains.

While there have been many cases where simplified approaches have failed, we still often use the framework to address sustainability challenges, focusing only on isolated individual indicators (such as greenhouse gas emissions, energy or freshwater consumption), rather than sustainability as a comprehensive, systemic, multidimensional issue.

Much of the current sustainability efforts in the chemical industry focus on incremental improvements in products and processes through increased efficiency, but this approach is imperfect. Instead, we need disruptive changes to meet the demands of a sustainable society in the future.

It is necessary to propose solutions from the overall plan to ensure that there are no deviations or accidents. Therefore, the traditional approach of simplification must be combined with integrated systematic thinking to provide guidance for the design of sustainable societies in the future.

For example, knowing the properties of a molecule is only a minimum requirement, as is knowing the potential harm of such a molecule. The way a single problem is addressed may create other challenges (for example, the use of biofuels may increase pressure on land use and competition for food).

There are now so-called "collaborative solutions," or solutions that advance multiple sustainability issues in concert.

For example, there is a rich metal catalyst on Earth, which can use sunlight to decompose water to produce hydrogen, achieve energy storage, and can produce water after hydrogen combustion for energy recovery.

Another example is designing a future fuel that is produced in a "carbon neutral" way, which can simultaneously achieve the dual purpose of reducing air pollution emissions and improving engine efficiency.

While the debate about cascading nonlinear problems is still ongoing (e.g., increased fossil energy extraction → greater pressure on freshwater use → refugee migration → social unrest and military conflict), it is possible to solve these problems through systematic thinking and design of "collaborative solutions", where "less talk and less action" will create more results with less effort (e.g. Using CO2 to convert waste into raw materials → avoiding the use of toxic agents such as phosgene → reducing CO2 emissions → slowing rising CO2 levels → mitigating global climate change).

Expand the definition of performance from a technical function to a sustainability function

To achieve fundamental change in the chemical industry, the concept of performance needs to be redefined.

Since commercial synthetic chemistry began with the introduction of Perkin purple dye in the mid-19th century, chemical products have always been judged by performance. Performance is almost entirely defined as the ability to perform narrowly defined functions efficiently (e.g., the color of a dye, the stickiness of a glue, the insecticidal ability of an insecticide).

However, focusing on a single function can lead to other undesirable outcomes. We must broaden our definition of performance to include all aspects beyond functionality, especially sustainability.

This expanded definition of performance requires process designers to understand not only the mechanics of the technical functions of chemical products, but also the hazards that these substances can cause.

This extended definition of performance implies that anyone who designs, invents, and intends to manufacture a chemical product must have knowledge of product-related hazards, which may be global, physical, or toxicological.

After more than a century of incidents or accidents with adverse consequences for human health and the environment, we still do not incorporate toxicology into chemistry training curricula. To think about chemical hazards in the same way that we think about chemical properties, we need to have courses in our education that extend the definition of function as well as technology to include the attributes of sustainability.

The redefinition of performance also directly affects the business model of the chemical industry, as part of the strategic reallocation is to reduce the amount of materials required, thereby reducing the potential harm to the entire ecosystem.

The "F-factor" section contains the concept of maximum performance, which is to maximize the function while using the least amount of chemicals, similar to the application of Moore's Law on integrated circuits today.

The concept of material minimization is to reduce the use of raw materials, energy consumption in processing and transportation, waste generation, waste management and associated hazards.

This philosophy can also be applied to other businesses and shift the way to profit from selling the material itself to providing related peripheral services (such as the coloring, lubrication or cleaning of the material) while reducing harm.

This shift in philosophy is in line with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization's emphasis on "chemical leasing" - selling chemicals for function, rather than quantity.

This can achieve profit maximization and sustainable development while reducing material production costs and improving material properties.

Intrinsic properties of future chemical products

Future chemical products will be designed to reduce or even eliminate hazards while maintaining functional effectiveness.

Here, the definition of hazards is broad, including physical hazards (such as explosions and corrosion), global hazards (such as greenhouse gases and ozone depletion), and toxicological hazards (such as carcinogenesis and endocrine disruption).

Traditional ways of dealing with hazardous chemicals are often to prevent leaks, such as using protective equipment or exhaust gas purifiers; But when prevention and control mechanisms fail, the results can be catastrophic.

The idea of green chemistry is to shift the focus of risk reduction to harm reduction.

It is important to note that the hazard is an inherent property of the chemical and a result of design choices. Therefore, it is necessary to redesign chemical products and production processes after in-depth understanding of molecular mechanisms, so as to avoid physical and mental damage to human beings and damage to the environment.

An expanded definition of performance should therefore include the function of chemicals and their inherent properties, including their renewability, non-toxicity and degradability in the environment.

reproducibility

The transition from petrochemical to renewable chemistry must be carefully designed in an integrated system environment, taking into account possible negative impacts from factors such as land conversion, water use or competition with food production.

Crucially, the use of benign processes enables an important shift towards renewable feedstocks, including the shift from linear to circular processes.

Therefore, materials that are currently considered low value must be disposed of as renewable raw materials in the future. Examples of the use of low-value "waste" include the conversion of lignin from paper mill waste into feedstock for the production of vanillin, and the partial replacement of petroleum-based propylene oxide with direct use of carbon dioxide in polyurethane production, which would significantly reduce carbon emissions while improving other environmental parameters.

Chemists need to think more deeply about the problem of "waste design" : how to adjust the synthesis route to minimize the disposal of by-products, or make by-products usable as feedstock

nontoxicity

The design of non-toxic chemical products needs to be achieved through cooperation in chemistry, toxicology, genomics and other related fields. There is a need to understand and study the underlying molecular mechanisms, including how molecules are distributed, absorbed, metabolized, and excreted in the body, and how physico-chemical properties such as solubility, reactivity, and cellular permeability affect these processes.

Work is under way to predict and model toxicity. However, models rely on limited available toxicity data, which is currently being collected by a number of projects in the US and the EU.

degradability

The chemicals of the future must be designed to be non-persistent compounds that degrade easily and do not damage the environment.

For example, a pesticide with very low toxicity to mammals and rapid degradation can be chemically modified to improve its biodegradability; Some renewable sources of succinic acid based plasticizers can be used to synthesize non-toxic polyvinyl chloride (PVC) polymers that can be rapidly degraded.

Molecular characteristics and environmental mechanisms that lead to persistence need to be understood in order to build predictive models. Routine assessment of the potential persistence of synthetic compounds is critical for every (newly) designed compound that may eventually be distributed in the environment (such as pharmaceuticals and personal care products).

Paradoxically, stability may be a desirable property when considering the energy expenditure of the compound modification, the synthetic route, and the molecular complexity.

An important consideration is to evaluate whether this "investment" has value-added applications, rather than simply pursuing the design of a degradation pathway.

Highly complex molecules of renewable origin that are not natural compounds need to be re-integrated into the value chain by designing reuse or recycling routes; If the molecule is a natural compound, it is biodegradable regardless of its complexity.

Redesigning the chemical value chain with non-fossil raw materials

Today's chemical industry is almost entirely dependent on oil, natural gas and coal as a source of carbon. The petrochemical value chain that emerged in the second half of the 20th century formed a highly integrated network, sometimes referred to as the "oil tree."

In terms of embedded energy, embedded materials (including water), waste generation, and environmental and economic costs, the use of green conversion methods and processes reflects the advantages of the transition from fossil resources to renewable resources

Petrochemical refineries produce fewer than a dozen modules, especially short-chain olefins and aromatics, which together with synthetic gases become the stems of the oil tree, which in turn derive the trunk, branches and leaves of the oil tree, ultimately forming more than 100,000 chemicals that make up the molecular diversity.

Much of the value of petrochemistry comes from synthesis methods that introduce functional groups into molecules. Therefore, the availability of raw materials and the function of the required products have a direct feedback effect on the development of chemical production routes and processes.

The improvement of synthetic methods will undoubtedly remain a major area of research with the most direct impact on the environment. Due to the depletion of resources, global climate change and the production of toxic by-products, oil is not a sustainable option. Ultimately, new value chain designs based on non-fossil carbon sources and renewable resources will pave the way for a closed cycle. This change in form marks the beginning of the next industrial evolution in chemistry.

The use of renewable carbon resources becomes competitive, which requires major scientific breakthroughs and innovations, and advanced hydrogen technology and electrochemical processes should be actively studied to develop and utilize energy.

Among carbon sources, lignocellulosic biomass and carbon dioxide are among the most abundant raw materials on Earth, and their quantities are sufficient to "de-petroleum" the chemical value chain. Recycled plastic materials are another potentially rich source of carbon within the circular economy framework.

In contrast to fossil resources consisting solely of hydrocarbon, these feedstocks are composed of highly oxidized and "over-functionalized" molecules. Therefore, their transformation requires new integrated ideas and methods to achieve.

One option for addressing the challenge of complexity is to eliminate it.

For example, by combining synthetic gas intermediates with Fischer-Tropsch synthesis technology, oil substitutes are produced.

Thus, almost any non-fossil feedstock can add additional "roots" to the oil tree; The "green carbon" is then passed through all the existing "branches" and "leaves". This approach leverages established knowledge and infrastructure to reorganize valuable functions.

Another strategy is to take advantage of the inherent complexity of renewable raw materials to achieve a shortcut to target functional group molecules.

For example, the microbial fermentation of waste glycerol or sugar at room temperature to produce important chemical products (such as 1, 3-propylene glycol or succinic acid) in water is increasingly competing with the multi-step petrochemical route.

A similar approach applies to carbon dioxide, which can be integrated into the value chain through existing chemical products.

Bespoke chemicals and biocatalites that can adapt to changes in feedstock quality and fluctuations in energy supply, as well as the development of highly integrated and energy-efficient purification processes, will be important scientific drivers behind this development.

Perhaps even better, renewable raw materials offer entirely new chemical modules that can drive functional improvements without historically negative impacts on human health and the environment.

For example, recently, monosaccharide derived synthesis of furan dicarboxylic acid (FDCA) has aroused interest as a potential base material for novel polyester products, such as carbonated liquid containers; Polymer chains that incorporate carbon dioxide directly into consumer products have been industrialised. An increasing number of new synthetic methods based on the selective coupling of carbon dioxide and hydrogen with other substrates illustrate their great potential for building functional groups in the later stages of product synthesis.

In this field, it is obvious that the systematic integration of molecular and engineering science with product properties will enable the unification of energy and matter in the chemical-energy relationship and create new opportunities for the coupling of chemistry with agriculture, steel, cement and other industries.

Deconstructing highly complex target molecules through "counter-synthetic analysis" to design their synthesis from existing feedstocks and synthesis methods is a central pillar of synthetic organic chemistry today.

The same conceptual idea can be translated into a new design framework for synthesizing target products from renewable raw materials.

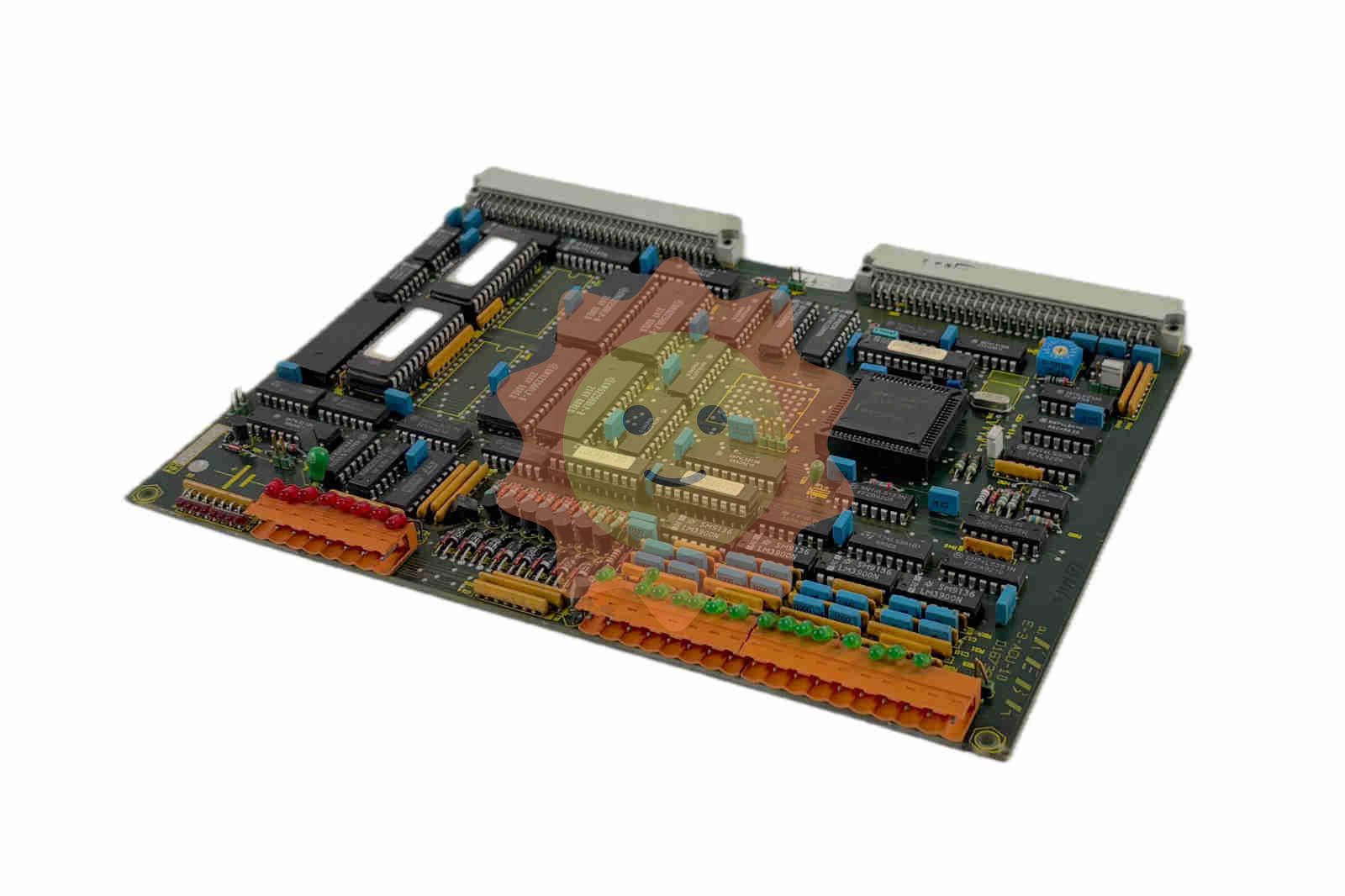

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

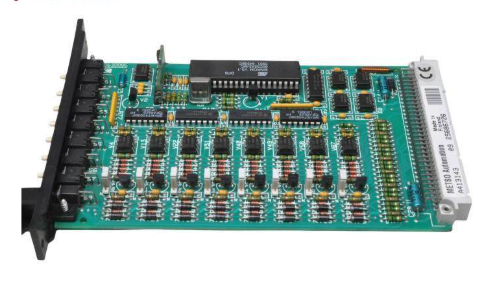

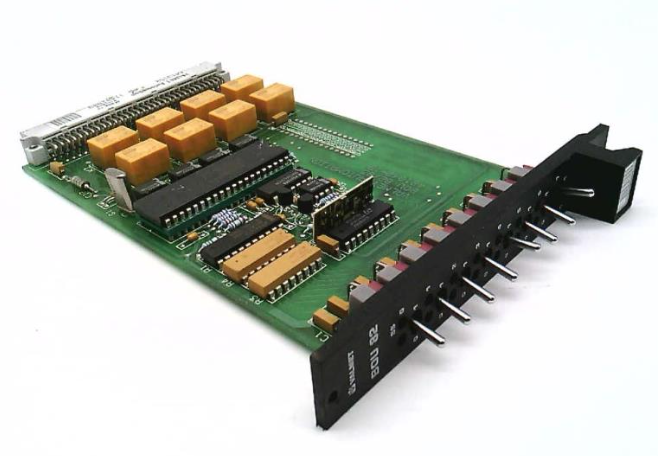

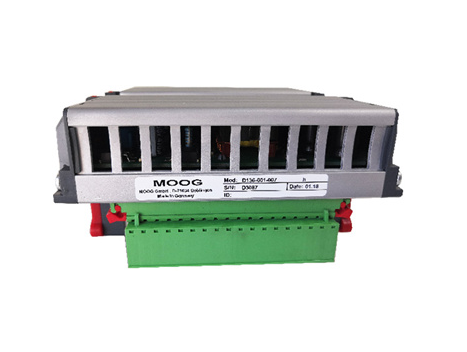

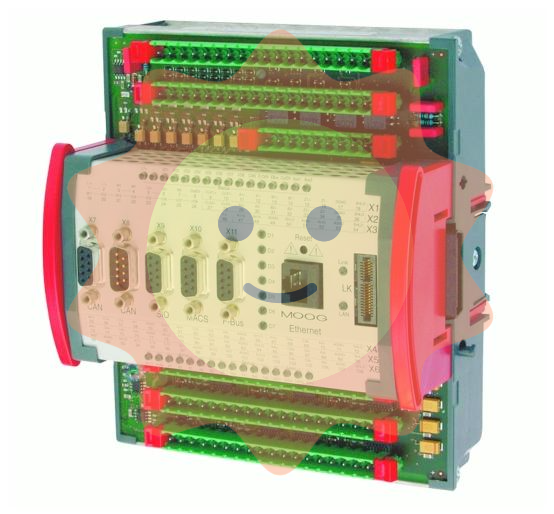

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands