Traditional American community life in the shadow of tech giants

This means that the worst damage from the pandemic will fall where there is the least cushion. The same goes for the impact on individuals. In Las Vegas, public officials painted frames on parking lot asphalt in an attempt to keep homeless people sleeping there six feet apart. In Jersey Beach, New Jersey, a food bank called Fulfill has seen a 40 percent increase in demand, serving more than 364,000 meals to those in need. Nationwide, employment levels for those earning more than $28 an hour have returned to pre-pandemic levels in the fall of 2020, while those earning less than $16 an hour have seen more than a quarter of their jobs cut.

An industry giant that is hard to check

In Dayton, Todd Swaros, who was involved in another car accident, also lost his job at the paperboard factory. Before the pandemic began, he worked at a Popeye fried chicken restaurant not far from where he and Sarah and their children lived, a half-hour drive south of Dayton. When the pandemic struck, his hours were cut and the restaurant offered drive-in only, while Sarah struggled to homeschool the children in their small home. The stress of life had predictable consequences: In May, they broke up again and agreed to share custody of their children. Popeye Fried Chicken refused to raise Todd's hourly wage to $11, and he was frustrated. By October, he had taken a logistics-related job at a tire warehouse adjacent to the small Amazon fulfillment centers that are now popping up across the country. He makes $13 an hour, almost as much as he made as a paperboard worker.

In Baltimore, a 26-year-old woman named Shayla Melton is trying to decide whether to go back to work at Amazon. Before becoming pregnant with her second child, just as the pandemic hit, she had been working as a picker at the Broning Highway warehouse, where the former General Motors plant was located. The husband, who also works as a picker but at a different Amazon warehouse, also took a leave of absence because of the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases there.

Initially, as a response to the epidemic, Amazon announced that it was establishing a charitable fund for temporary workers and contract delivery drivers who lacked health insurance and encouraged the public to donate to the cause. The move was met with derision by some. It also promises two weeks of paid leave to any diagnosed employee and unpaid leave to anyone who wants to stay home to prevent illness without being penalized for missing work. It offered a temporary $2 hourly wage incentive to those who stayed on the job. It set up temperature checks and virus detection stations for workers on site. The company also distributes masks and provides hand sanitizer and disinfectant.

At the Thornton Warehouse in Colorado, Hector Torres watched the measures take effect. One day, a small group of cleaners arrived dressed up to look like suits from the movie Ghostbusters. The usual group stretching during shifts has been canceled, making physical work even more dangerous, and now they have to work alone without a partner, like loading boxes into a truck alone. Most disturbing to Hector was the comparison with employees at the company's headquarters, who were allowed and encouraged to work from home. The warehouse's precautions seemed so inadequate that he decided to continue living in the basement until the summer. For months, he didn't even hug his wife or children; His only company was the family dog and cat. "We don't sit together, we don't do anything together." "I would assume I was exposed to something every day," he said.

Meanwhile, new employees keep arriving. Several came from similar backgrounds: a former industrial engineer, a former litigator, and a former real estate company owner. "I see a lot of people around me who don't have a choice." "We have become economic refugees," he said. Many of the other workers were fairly young, and Hector would talk to them, urging them to move on as quickly as possible. "Time is running out," he told them. "You're young. Leave the warehouse while you still have a choice."

At Amazon's warehouse in France, union demands for safety measures forced it to shut down for weeks, eventually leading to negotiations in which Amazon agreed to reduce shifts by 15 minutes without a pay cut in order to provide more social distancing during crowded shifts. In non-union American warehouses, people vent their frustrations in different ways. Out of sight of the warehouse cameras, the trailer was covered with graffiti such as "Welcome to Hell" and "Fuck Bezos." With workers sharing their frustrations online and organizing protests in some warehouses, the pandemic may usher in a new era of workplace activism.

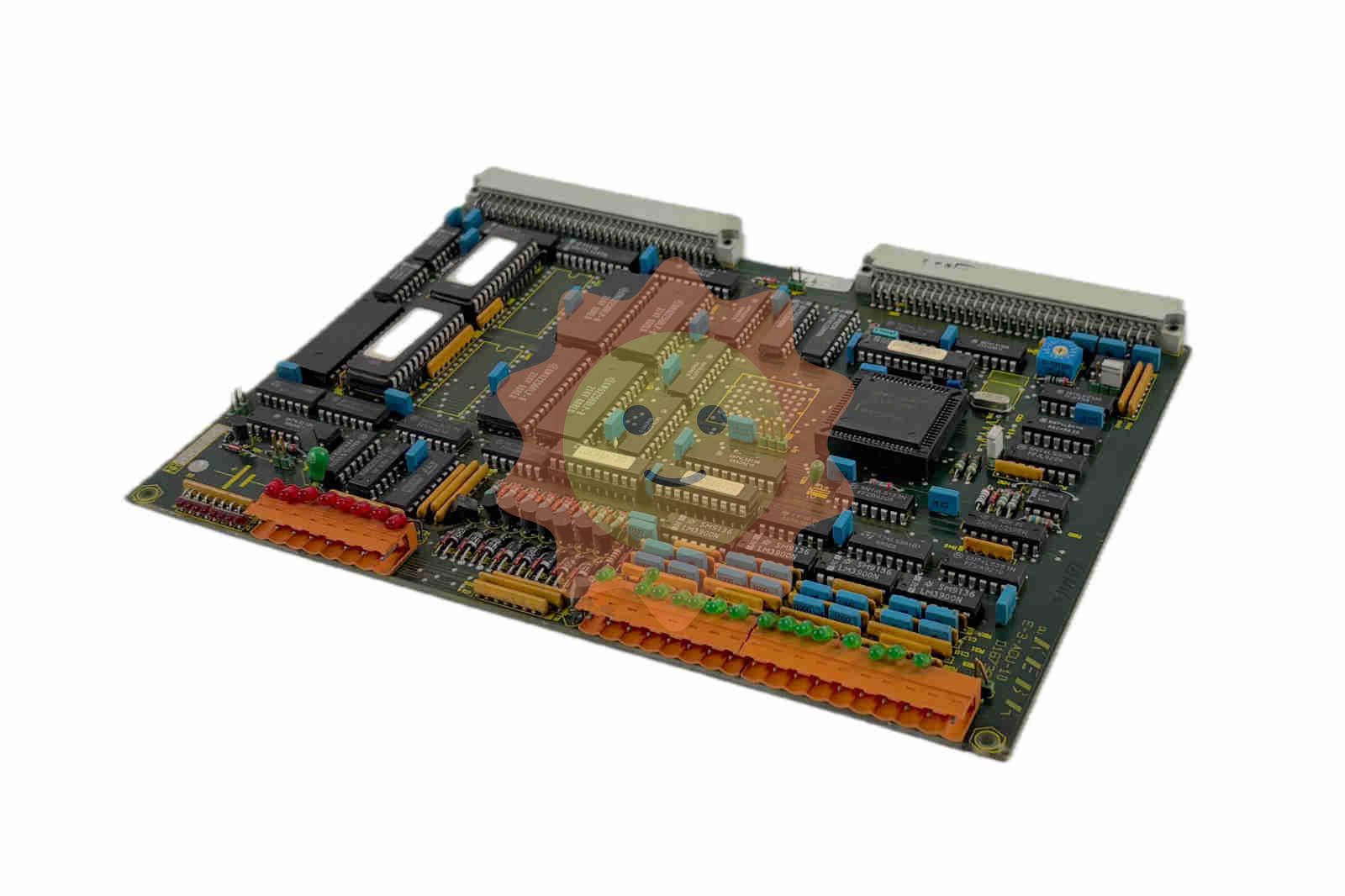

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

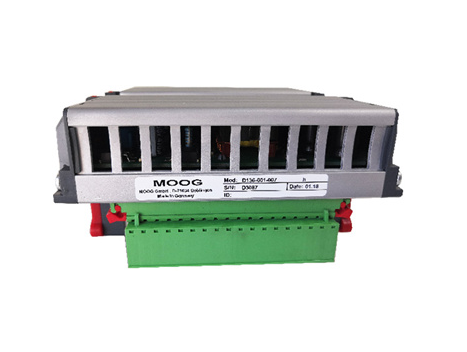

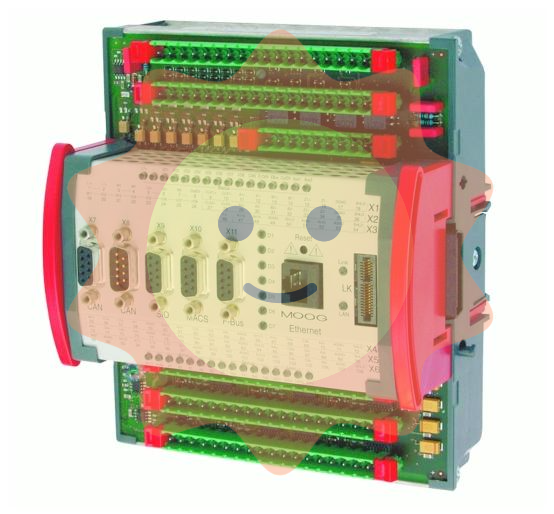

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands