Traditional American community life in the shadow of tech giants

On the Saturday before Easter in 2020, I set off from my home in Baltimore to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where I grew up. Despite Maryland's stay-at-home ban due to COVID-19, I decided to visit my parents, whom I hadn't seen in months. To maintain a safe distance, I planned to spend the night elsewhere; We planned to go out together on Easter Sunday.

I drove out of Baltimore in the late afternoon. Along the east Coast of the United States, Interstate 95, a traffic corridor that is often congested, was emptier than I had ever seen it before. A digital highway sign overhead flashes the words "Save Life, advocate home." I'd never been near a war zone, but I thought it might feel a bit like it does now - only the most necessary or foolish travelers would hang out, while the rest of the world curled itself up.

Except there are no personnel carriers or ammunition carriers in this theater. Instead, there was just truck after truck. Of the few vehicles on the road, most are tractor-trailers, and the vast majority of them belong to Amazon. I counted more than two dozen Amazon trucks on a 100-mile stretch between Baltimore and southern New Jersey that was too dark to read the signs. Over the past few years, I've encountered many Amazon vans on my travels around the country. But I've never seen them so densely.

"Change" is on a super-fast track

If we're in the middle of a battle against the coronavirus, Amazon is serving as our troop carrier. In this battle, mobilizing for attack means full retreat and self-isolation, and Amazon is serving that mobilization, sending everything to people's homes to keep them in their homes. Suddenly, meeting needs online became a civic duty, a cause bigger than ourselves. As a result, (at least for some people) an act of convenience that once required second thoughts has now been given a sense of justice. "One-click order", people use this to level the curve of the epidemic.

A large number of express cartons arrived at home. Typically, deliveries stay on the porch or in the garage for a day or two to prevent the delivery person from picking up virus particles. After the quarantine period, the boxes entered people's homes.

There were so many boxes and so many orders that the company, known for its unparalleled logistics operations, struggled to keep up. Amazon announced plans to add 100,000 warehouse workers and, a few weeks later, 75,000 more. The company told buyers and third-party sellers that "less important orders" would be deferred. Most surprisingly, it has temporarily taken down some of the web features designed to get shoppers to buy more from the site: this time, Amazon is discouraging people from spending more. The company had its eyes on the future, but when it really became the ultimate store, it wasn't ready. At least not yet.

Emergency measures are temporary. The old buying incentives are back, and there are no restrictions on non-essentials. It turns out that Amazon is actually using algorithms to find new ways to get product manufacturers to sell exclusively on its website, abandoning other retailers. As the peak of the national crisis passed in the spring of 2020, the consequences became clear. The pandemic has sent a series of developments in American life into hyper-velocity, like a jumble of film roll.

News organizations, which have long lost much of their advertising dollars to Silicon Valley, are now losing what little revenue they have left because business has stalled - and many are cutting entire newsrooms or putting staff on shifts to survive. As a result, news organizations have been short-staffed, both to cover the big story of the coronavirus pandemic and to cover the other big story in Minneapolis, the protests over the death of George Floyd. By August, things had gotten so bad that the Tribune Group, a newspaper chain, announced the permanent closure of its brick-and-mortar news operations, including the New York Daily News, the Orlando Sentinel and the Allentown Morning News. The Allentown Morning News reported in 2011 on workers who were left unconscious from heat exhaustion at a local Amazon warehouse. In December, Tribune closed the offices of the Hartford Courant, once Connecticut's largest newspaper and the oldest continuous publication in the United States.

Some traditional retail companies have survived the turmoil of the past 20 years, but now they are dying. Jcpenney, Neiman and apparel brand J.Crew filed for bankruptcy. Macy's temporarily closed all 775 stores and laid off nearly all of its 125,000 employees. Nordstrom, Amazon's neighbor in Seattle, announced thousands of job cuts. Small independent businesses across the United States are also facing widespread losses. In total, 25,000 retail stores are expected to close by the end of 2020, tripling the number of recent mass closures from pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, the same companies that have been reshaping economic trends for decades are getting bigger and more successful, the exact opposite of the economic hemorrhaging across the country. By the end of May 2020, in just two months, the combined market value of the five largest tech companies (Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google parent company Alphabet) had increased by a staggering $1.7 trillion, or 43%. And they're only going to get bigger: Together, they have $557 billion in cash. They used the cash to fund new acquisitions, boosting research and development spending to nearly $30 billion at a time when relatively smaller competitors were scaling back, an outlay larger than NASA's entire budget.

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

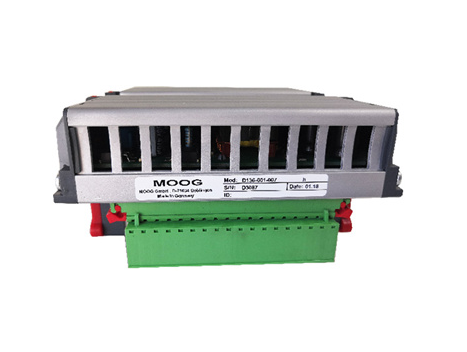

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands