Traditional American community life in the shadow of tech giants

On the Saturday before Easter in 2020, I set off from my home in Baltimore to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where I grew up. Despite Maryland's stay-at-home ban due to COVID-19, I decided to visit my parents, whom I hadn't seen in months. To maintain a safe distance, I planned to spend the night elsewhere; We planned to go out together on Easter Sunday.

I drove out of Baltimore in the late afternoon. Along the east Coast of the United States, Interstate 95, a traffic corridor that is often congested, was emptier than I had ever seen it before. A digital highway sign overhead flashes the words "Save Life, advocate home." I'd never been near a war zone, but I thought it might feel a bit like it does now - only the most necessary or foolish travelers would hang out, while the rest of the world curled itself up.

Except there are no personnel carriers or ammunition carriers in this theater. Instead, there was just truck after truck. Of the few vehicles on the road, most are tractor-trailers, and the vast majority of them belong to Amazon. I counted more than two dozen Amazon trucks on a 100-mile stretch between Baltimore and southern New Jersey that was too dark to read the signs. Over the past few years, I've encountered many Amazon vans on my travels around the country. But I've never seen them so densely.

"Change" is on a super-fast track

If we're in the middle of a battle against the coronavirus, Amazon is serving as our troop carrier. In this battle, mobilizing for attack means full retreat and self-isolation, and Amazon is serving that mobilization, sending everything to people's homes to keep them in their homes. Suddenly, meeting needs online became a civic duty, a cause bigger than ourselves. As a result, (at least for some people) an act of convenience that once required second thoughts has now been given a sense of justice. "One-click order", people use this to level the curve of the epidemic.

A large number of express cartons arrived at home. Typically, deliveries stay on the porch or in the garage for a day or two to prevent the delivery person from picking up virus particles. After the quarantine period, the boxes entered people's homes.

There were so many boxes and so many orders that the company, known for its unparalleled logistics operations, struggled to keep up. Amazon announced plans to add 100,000 warehouse workers and, a few weeks later, 75,000 more. The company told buyers and third-party sellers that "less important orders" would be deferred. Most surprisingly, it has temporarily taken down some of the web features designed to get shoppers to buy more from the site: this time, Amazon is discouraging people from spending more. The company had its eyes on the future, but when it really became the ultimate store, it wasn't ready. At least not yet.

Emergency measures are temporary. The old buying incentives are back, and there are no restrictions on non-essentials. It turns out that Amazon is actually using algorithms to find new ways to get product manufacturers to sell exclusively on its website, abandoning other retailers. As the peak of the national crisis passed in the spring of 2020, the consequences became clear. The pandemic has sent a series of developments in American life into hyper-velocity, like a jumble of film roll.

News organizations, which have long lost much of their advertising dollars to Silicon Valley, are now losing what little revenue they have left because business has stalled - and many are cutting entire newsrooms or putting staff on shifts to survive. As a result, news organizations have been short-staffed, both to cover the big story of the coronavirus pandemic and to cover the other big story in Minneapolis, the protests over the death of George Floyd. By August, things had gotten so bad that the Tribune Group, a newspaper chain, announced the permanent closure of its brick-and-mortar news operations, including the New York Daily News, the Orlando Sentinel and the Allentown Morning News. The Allentown Morning News reported in 2011 on workers who were left unconscious from heat exhaustion at a local Amazon warehouse. In December, Tribune closed the offices of the Hartford Courant, once Connecticut's largest newspaper and the oldest continuous publication in the United States.

Some traditional retail companies have survived the turmoil of the past 20 years, but now they are dying. Jcpenney, Neiman and apparel brand J.Crew filed for bankruptcy. Macy's temporarily closed all 775 stores and laid off nearly all of its 125,000 employees. Nordstrom, Amazon's neighbor in Seattle, announced thousands of job cuts. Small independent businesses across the United States are also facing widespread losses. In total, 25,000 retail stores are expected to close by the end of 2020, tripling the number of recent mass closures from pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, the same companies that have been reshaping economic trends for decades are getting bigger and more successful, the exact opposite of the economic hemorrhaging across the country. By the end of May 2020, in just two months, the combined market value of the five largest tech companies (Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google parent company Alphabet) had increased by a staggering $1.7 trillion, or 43%. And they're only going to get bigger: Together, they have $557 billion in cash. They used the cash to fund new acquisitions, boosting research and development spending to nearly $30 billion at a time when relatively smaller competitors were scaling back, an outlay larger than NASA's entire budget.

Winner of winners

Amazon is the winner of the winners. Its first-quarter sales were more than a quarter higher than a year earlier, even as overall retail sales plunged. In mid-April 2020, just as the pandemic was nearing its deadliest phase, Amazon's stock was surging, up more than 30% for the year, while Bezos' net worth increased by $24 billion in just two months. In late July, Amazon announced that its second-quarter profit had doubled and sales were up a staggering 40 percent from a year earlier. The company's share price soared on the news: in early September, it was up 84% for the year, more than double the rise of other tech giants. In a note to investors, one industry analyst said: "Simply put, in our view, the COVID-19 pandemic has injected a growth hormone into Amazon."

To handle the surge in business, Amazon added more than 425,000 employees worldwide between January and October of that year, bringing its total non-seasonal workforce in the U.S. to 800,000 and its global total to more than 1.2 million (a figure that doesn't include the 500,000 drivers who deliver packages), a 50 percent increase from the previous year. To accommodate these workers, Amazon has gone on a building and leasing spree, opening 100 buildings in September and adding nearly 100 million square feet of warehouse space by the end of 2020, a roughly 50 percent expansion rate. Warehouses aren't the only part of the company in high demand: As hundreds of millions of human interactions move online every day, Amazon's data centers are expanding for customers like videoconferencing software company Zoom.

In midsummer, Amazon announced the huge profits it had made during the coronavirus pandemic on the same day that the Commerce Department reported that the U.S. economy shrank by nearly 10 percent, the biggest quarterly decline on record. In other words, at a time when America as a whole is at its lowest ebb, Amazon is prospering more than ever: the fortunes of the company and the country in which it operates have diverged.

This profound imbalance of fortunes has largely contributed to the political upheavals of this era. And, as the horrifying year of 2020 draws to a close, it is clear that one of the first tasks facing President-elect Biden and the incoming administration will be to decide how to resolve this disagreement. The US cannot afford to let it continue to expand.

The vulnerable have borne the heaviest losses

While the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the concentration of wealth and power in some of the most dominant companies, it is possible to imagine ways that prosperity and dynamism could be spread more widely across the country. Manhattan's upscale apartment buildings are almost completely empty, and some New Yorkers who fled the city are considering moving out permanently. Some say the pandemic could mean the end of the office era, with us finally free to work from anywhere. Why spend so much money in a big city if you no longer need to report to a building downtown? Why not move to a quiet village up north, or even Syracuse, Erie or Akron?

These ideas, romantic as they are, have the aura of a simpler time, when Samuel Grunbach sent his son and son-in-law to the small Pennsylvania city to start the family business. But such thinking flies in the face of harsh economic realities. The digital economy has produced take-all companies and cities, and it is hard to imagine that the digital "leap forward" brought about by the pandemic lockdowns will not exacerbate winner-takes-all situations, with tech giants and the cities associated with them further consolidating their market power. Facebook seized the moment to lease the monumental former post office building across from Pennsylvania Station in New York and convert all 730,000 square feet into office space.

Amazon's announcement that it would add at least 2,000 white-collar workers to the former Lord's and Taylor's flagship department store on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue came as no surprise. There are currently more than 50,000 Amazon employees in Seattle, and the company has announced that it will add another 25,000 in Bellevue, across Lake Washington, by 2025 - with that, the Seattle metro area will absorb the same number of employees as the entire HQ2 complex in Northern Virginia, further cementing its long-established prosperity. While rents and apartment prices in the wealthiest cities are beginning to fall from stratospheric highs, the rising demand for office parks and apartment communities in New York's suburbs, for properties in western ski resorts and for the Hamptons school district suggests that any missing benefits will remain largely within the confines of winner-take-all metropolises and their satellite towns, and will never trickle down to smaller cities farther afield.

At the same time, the federal government's COVID-19 relief package only provides municipal aid to cities with populations of more than 500,000, and the financial situation of smaller cities will deteriorate further. There are already signs that restaurant and bar closings are hurting places like St. Louis and Detroit in particular, where a belated revival has been fueled in part by budding nightlife options. In August, American Airlines announced that it would stop flights to 15 small and medium-sized cities in China, which is bound to further accelerate the isolation and decline of these cities.

This means that the worst damage from the pandemic will fall where there is the least cushion. The same goes for the impact on individuals. In Las Vegas, public officials painted frames on parking lot asphalt in an attempt to keep homeless people sleeping there six feet apart. In Jersey Beach, New Jersey, a food bank called Fulfill has seen a 40 percent increase in demand, serving more than 364,000 meals to those in need. Nationwide, employment levels for those earning more than $28 an hour have returned to pre-pandemic levels in the fall of 2020, while those earning less than $16 an hour have seen more than a quarter of their jobs cut.

An industry giant that is hard to check

In Dayton, Todd Swaros, who was involved in another car accident, also lost his job at the paperboard factory. Before the pandemic began, he worked at a Popeye fried chicken restaurant not far from where he and Sarah and their children lived, a half-hour drive south of Dayton. When the pandemic struck, his hours were cut and the restaurant offered drive-in only, while Sarah struggled to homeschool the children in their small home. The stress of life had predictable consequences: In May, they broke up again and agreed to share custody of their children. Popeye Fried Chicken refused to raise Todd's hourly wage to $11, and he was frustrated. By October, he had taken a logistics-related job at a tire warehouse adjacent to the small Amazon fulfillment centers that are now popping up across the country. He makes $13 an hour, almost as much as he made as a paperboard worker.

In Baltimore, a 26-year-old woman named Shayla Melton is trying to decide whether to go back to work at Amazon. Before becoming pregnant with her second child, just as the pandemic hit, she had been working as a picker at the Broning Highway warehouse, where the former General Motors plant was located. The husband, who also works as a picker but at a different Amazon warehouse, also took a leave of absence because of the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases there.

Initially, as a response to the epidemic, Amazon announced that it was establishing a charitable fund for temporary workers and contract delivery drivers who lacked health insurance and encouraged the public to donate to the cause. The move was met with derision by some. It also promises two weeks of paid leave to any diagnosed employee and unpaid leave to anyone who wants to stay home to prevent illness without being penalized for missing work. It offered a temporary $2 hourly wage incentive to those who stayed on the job. It set up temperature checks and virus detection stations for workers on site. The company also distributes masks and provides hand sanitizer and disinfectant.

At the Thornton Warehouse in Colorado, Hector Torres watched the measures take effect. One day, a small group of cleaners arrived dressed up to look like suits from the movie Ghostbusters. The usual group stretching during shifts has been canceled, making physical work even more dangerous, and now they have to work alone without a partner, like loading boxes into a truck alone. Most disturbing to Hector was the comparison with employees at the company's headquarters, who were allowed and encouraged to work from home. The warehouse's precautions seemed so inadequate that he decided to continue living in the basement until the summer. For months, he didn't even hug his wife or children; His only company was the family dog and cat. "We don't sit together, we don't do anything together." "I would assume I was exposed to something every day," he said.

Meanwhile, new employees keep arriving. Several came from similar backgrounds: a former industrial engineer, a former litigator, and a former real estate company owner. "I see a lot of people around me who don't have a choice." "We have become economic refugees," he said. Many of the other workers were fairly young, and Hector would talk to them, urging them to move on as quickly as possible. "Time is running out," he told them. "You're young. Leave the warehouse while you still have a choice."

At Amazon's warehouse in France, union demands for safety measures forced it to shut down for weeks, eventually leading to negotiations in which Amazon agreed to reduce shifts by 15 minutes without a pay cut in order to provide more social distancing during crowded shifts. In non-union American warehouses, people vent their frustrations in different ways. Out of sight of the warehouse cameras, the trailer was covered with graffiti such as "Welcome to Hell" and "Fuck Bezos." With workers sharing their frustrations online and organizing protests in some warehouses, the pandemic may usher in a new era of workplace activism.

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

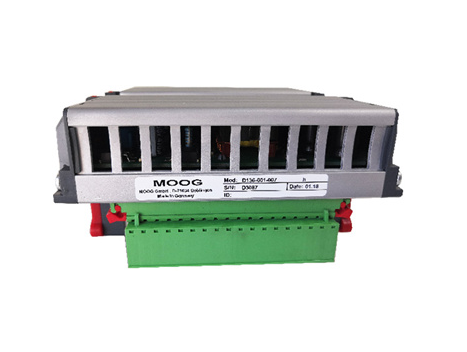

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands