What inspiration does the world's "largest generic drug" company bring to China?

The night of December 23, 2002, is equivalent to New Year's Eve in the United States. Then-president George W. Bush strapped a camera to his beloved Scottish Terrier and posted the video online. The topic of conversation across America that day was the White House Christmas decorations.

But outside the Food and Drug Administration, the parking lot was packed with people, and no one cared about the president's dog.

Representatives of generic leader Teva and other "friends" gathered here, waiting for the FDA to open the next morning and be the first to submit a copy of Modafinil. It's a drug for narcolepsy, potentially a billion dollar product.

According to the holiday rules of the United States, the Christmas holiday begins on the afternoon of December 24. These queuing enterprises must pass the materials up early on the 24th, otherwise they may have to wait until after January 5, which is sure to fall behind others.

It's been a long night. The Teva rep is freezing. They envied the Ranbaxy people next door: Ranbaxy had arrived in a stretch limo and could take turns taking a nap. And Teva just paid for a hotel room nearby, which is a long way back and forth.

In order to seize the exclusive production rights of the "first imitation" for 180 days, such a story will happen every time. The FDA had to change its policy to say that there was no need to wait in line overnight, as long as applications were submitted on time and approved in no particular order. And the FDA sent a letter to businesses asking them to stop using parking lots as campgrounds, "especially if they stay for a few weeks."

It's not hard to blame generic drug companies. After all, "put the raw material in the mixing bucket, and out comes gold."

This is how Teva has been selling medicine from Jerusalem to the world, barrel by barrel, for more than 120 years. In 2016, Teva was included in the Fortune Global 500 list for the first time, becoming the second Israeli company to do so.

The world's "largest generic drug" company has a lot to learn from China's current rush to "go overseas" domestic drug companies.

First, small countries born big pharmaceutical companies

Teva has always been a global benchmark in the generics industry, truly taking generics to the extreme.

The founding of Teva is closely related to the history of the founding of Israel. More than 100 years ago, the Zionist movement called on Jews who had been expelled and scattered around the world to return to Jerusalem and establish a "publicly recognized and legally secure state." There was a global wave of Jewish emigration.

Teva's predecessor, a drug supplier called S.L.E., was founded during this period.

The name is taken from Chaim Salomon, Moshe Levin, and Yitschak Elstein, three Jewish Jerusalem-based pharmacists. Due to the lack of funds and resources, the S.L.E has no production capacity, and they only use camels and donkeys to sell medicines and other goods to the Palestinian areas. In modern parlance, this is a pharmaceutical distribution enterprise.

The turning point came during World War II. Under the Nazi anti-Semitism campaign, a large number of Jews from Germanic areas fled to the Middle East, including some scientists and business talents. With the help of these professionals, S.L.E. established a drug manufacturing facility in Palestine and renamed the company Teva Pharmaceuticals.

At this time, Teva has not only done medicine circulation, but has become a complete production and marketing capacity of the pharmaceutical factory. According to Teva's official website, during the war, because imports were cut off, local pharmaceutical factories such as Teva became the only source of drug supplies for local and neighboring countries.

On May 14, 1948, the state of Israel was proclaimed, along with tax breaks for foreign and domestic businesses "involved in nation-building." With the help of policy dividends, Teva expanded its production scale and solved the employment problem of a large number of people, becoming a "red man" in front of the Israeli authorities.

In 1951, Teva was listed on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, becoming one of the first listed companies in Israel.

Second, favorable policies toward the United States

Teva was born in a time of war, and its Jewish identity is delicate in the Western world. But Teva didn't limit itself to Israel, and soon set its sights on the world.

In the early days, Teva's "going out" destinations were placed in North Africa, Europe and other neighboring countries and regions, and the days were also handsome. But soon its sights shifted further afield than Eurasia.

No wonder, Israel covers just over 20,000 square kilometers. By 2020, Israel's population will be just over 9.21 million, and its GDP will be about $0.4 trillion, equivalent to 2.5 trillion yuan. Only by opening up to the world can Teva have greater opportunities for development.

Soon, Teva set its sights on the United States. In 1984, the United States introduced the Hatch-Waxman Act, announcing the simplification of generic drug applications. Companies only need to provide corresponding testing evidence to show that their products are bioequivalent to the original drug can submit a marketing application. To address the concerns of generic drug companies, the United States also allows the first company to submit a generic drug application to the FDA to obtain a six-month period of market exclusivity and the right to sell the drug at a price close to the original.

This policy has greatly stimulated the supply of generic drugs in the US market. In 2000, the rate of generic prescriptions in the United States exceeded 50 percent.

After its establishment, Teva has not been able to embark on the road of original research and innovation like European and American pharmaceutical companies, but insists on generic drugs as its main business. On the one hand, Teva considers itself less capable of research and development than the century-old pharmaceutical companies in Europe and the United States; In the Middle East, on the other hand, there is a huge market opportunity for efficient and cheap generics. Teva knows exactly where it is.

In 1985, Teva first established TAG Pharma in a joint venture with W.R. race, a U.S. specialty chemical production giant, and then saw the opportunity to acquire Lemon at a low price because of the infamous quaaludes incident, and use Lemon's sales channels to gain a foothold in the United States.

This series of actions has brought rich returns to Teva, the first three years in the U.S. market, Teva's sales doubled; By the 1990s, the U.S. accounted for half of Teva's business.

Third, the merger thunder

Teva sticking to generics doesn't mean it's not expanding. Generics are available to everyone, but there are few major competitors. After Teva established its foothold, it began to further expand overseas markets.

As early as the 1970s, Teva has embarked on a path of expansion and acquisition for "going global", and most of them are famous people: such as Japan's third largest generic drug company Ocean Commodities, Peru's top 10 companies Corporacion Infarmasa and so on. It's just that these companies are generics, so Teva's expansion has been quiet.

In 2016, Teva acquired Actavis Generics, a generic drug giant owned by Allergan, for a total of $40.5 billion, directly joining the ranks of the top 10 global drug companies, becoming a pioneer in the history of generic drug mergers and acquisitions.

But successive acquisitions have saddled Teva with a heavy debt burden. With Actavis, Teva's total debt reached $57.8 billion, the highest in its history. Teva was forced to pay off its debts. At the end of 2020, the company still owes nearly $40 billion in debt.

Teva's massive debt problem won't be easy to solve. Unlike innovative drugs that can sell more than 10 billion dollars in a single product, the threshold for generic drugs is very low and the profit margin is limited. The only way to increase revenue is to expand sales, but when Teva expanded year after year, the United States pulled back.

In 2012, Congress approved the Generic Drug Fee Act (GDUFA), which heralded the end of the good times for generics.

Because of the long-term favorable policy in the United States, the number of generic drugs submitted to the FDA has soared, and the review has been backlogged. Data show that the average review time for each generic drug marketing application approval is nearly two and a half years, and by 2012, the FDA's backlog of applications has reached more than 2,800.

This is very similar to the situation before China's drug review reform in 2015, the difference is that the United States has opened an approval channel for innovative drug lists, so new drug applications are still very smooth.

In response to the accumulation of generic drug applications, the FDA issued a rule: Fees!

Generic drug companies pay a fee at the time of application, and the FDA uses this money to recruit people and set up a special generic drug office to improve the approval efficiency.

America's generics world is getting in on the act: everyone is paying, and the result is that generic drugs are piling up and getting cheaper.

In 2016, Teva had a 16% share of the U.S. generic drug market, but by 2020, that share had fallen to less than 10%. Teva's global revenue plunged from $22.385 billion in 2017 to $15.878 billion in 2021 due to a weak U.S. generic drug market and the expiration of one of its blockbuster patented drugs for multiple sclerosis.

Is there a way out for generic drugs?

In terms of quality, there's nothing to be said for Teva's generic. In 2020, the industry published a well-known book called The Truth about Generic Drugs. Us investigative journalist Catherine Eban writes in her book that when doctors replace drugs, they mostly choose Teva products because they know the company's products are "better quality" and "more effective."

Because according to the United States "Hatch-Waxman Act", after the expiration of a new drug patent, generic drugs no longer need to do experiments from scratch to prove the safety and efficacy of their own products, the quality of many generic drugs is difficult to fully guarantee.

In fact, both in the United States and China, generic drugs account for the vast majority of the drug market. Previously, Li Yan, president of Hisun Pharmaceutical, said that the current domestic market share of generic drugs and innovative drugs is roughly 95:5. Even in today's world of innovative drug concepts, most patients still use generic drugs.

In the sense that generic drugs are what truly safeguard the nation's health level, Teva's choice is not right. But Teva's generic is even better, because it lacks a moat. This is also the essential reason for domestic enterprises such as Hengrui to strengthen innovation.

In 2020, the FDA approved 755 generic drug applications (ANDAs), of which 80 were in China. The number of FDA ANDA applications in the first half of 2021 was 400, and China accounted for 40. Before innovative drugs, Chinese pharmaceutical companies have long gone to sea.

At the same time that a large number of ANDAs have been approved, some problems have been exposed in Chinese generic drugs. In 2018, the valsartan incident of Huahai Pharmaceutical allowed China's generic drug reputation to decline a lot. If innovative drugs represent the technological ceiling of the pharmaceutical industry, generics should be the "first man" in the pursuit of quality upgrades.

Although Teva has shown fatigue in the face of another round of competition, its product quality is still well-known, which is the foundation of Teva's global generics industry. For Chinese enterprises, more efforts to improve quality, can still obtain a certain space in the Red Sea market, even under the policy of collection, safety and reliability is still the most concerned issue of the competent authorities.

Getting back to "pharma" may be the most important lesson you can learn from Teva.

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

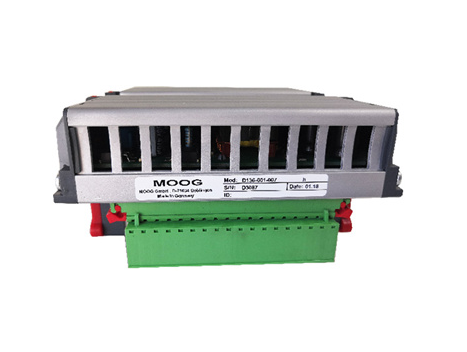

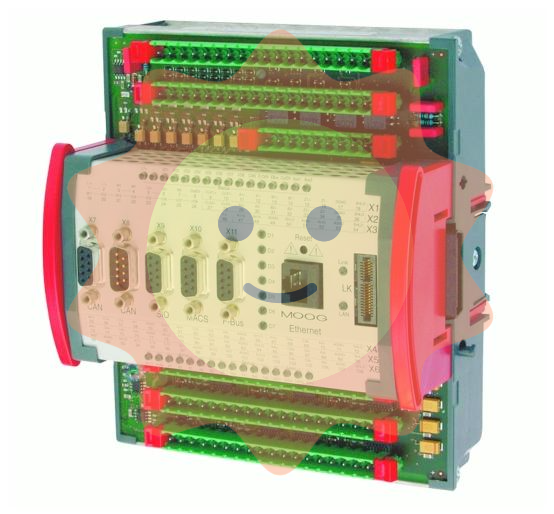

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands