What inspiration does the world's "largest generic drug" company bring to China?

The night of December 23, 2002, is equivalent to New Year's Eve in the United States. Then-president George W. Bush strapped a camera to his beloved Scottish Terrier and posted the video online. The topic of conversation across America that day was the White House Christmas decorations.

But outside the Food and Drug Administration, the parking lot was packed with people, and no one cared about the president's dog.

Representatives of generic leader Teva and other "friends" gathered here, waiting for the FDA to open the next morning and be the first to submit a copy of Modafinil. It's a drug for narcolepsy, potentially a billion dollar product.

According to the holiday rules of the United States, the Christmas holiday begins on the afternoon of December 24. These queuing enterprises must pass the materials up early on the 24th, otherwise they may have to wait until after January 5, which is sure to fall behind others.

It's been a long night. The Teva rep is freezing. They envied the Ranbaxy people next door: Ranbaxy had arrived in a stretch limo and could take turns taking a nap. And Teva just paid for a hotel room nearby, which is a long way back and forth.

In order to seize the exclusive production rights of the "first imitation" for 180 days, such a story will happen every time. The FDA had to change its policy to say that there was no need to wait in line overnight, as long as applications were submitted on time and approved in no particular order. And the FDA sent a letter to businesses asking them to stop using parking lots as campgrounds, "especially if they stay for a few weeks."

It's not hard to blame generic drug companies. After all, "put the raw material in the mixing bucket, and out comes gold."

This is how Teva has been selling medicine from Jerusalem to the world, barrel by barrel, for more than 120 years. In 2016, Teva was included in the Fortune Global 500 list for the first time, becoming the second Israeli company to do so.

The world's "largest generic drug" company has a lot to learn from China's current rush to "go overseas" domestic drug companies.

First, small countries born big pharmaceutical companies

Teva has always been a global benchmark in the generics industry, truly taking generics to the extreme.

The founding of Teva is closely related to the history of the founding of Israel. More than 100 years ago, the Zionist movement called on Jews who had been expelled and scattered around the world to return to Jerusalem and establish a "publicly recognized and legally secure state." There was a global wave of Jewish emigration.

Teva's predecessor, a drug supplier called S.L.E., was founded during this period.

The name is taken from Chaim Salomon, Moshe Levin, and Yitschak Elstein, three Jewish Jerusalem-based pharmacists. Due to the lack of funds and resources, the S.L.E has no production capacity, and they only use camels and donkeys to sell medicines and other goods to the Palestinian areas. In modern parlance, this is a pharmaceutical distribution enterprise.

The turning point came during World War II. Under the Nazi anti-Semitism campaign, a large number of Jews from Germanic areas fled to the Middle East, including some scientists and business talents. With the help of these professionals, S.L.E. established a drug manufacturing facility in Palestine and renamed the company Teva Pharmaceuticals.

At this time, Teva has not only done medicine circulation, but has become a complete production and marketing capacity of the pharmaceutical factory. According to Teva's official website, during the war, because imports were cut off, local pharmaceutical factories such as Teva became the only source of drug supplies for local and neighboring countries.

On May 14, 1948, the state of Israel was proclaimed, along with tax breaks for foreign and domestic businesses "involved in nation-building." With the help of policy dividends, Teva expanded its production scale and solved the employment problem of a large number of people, becoming a "red man" in front of the Israeli authorities.

In 1951, Teva was listed on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, becoming one of the first listed companies in Israel.

Second, favorable policies toward the United States

Teva was born in a time of war, and its Jewish identity is delicate in the Western world. But Teva didn't limit itself to Israel, and soon set its sights on the world.

In the early days, Teva's "going out" destinations were placed in North Africa, Europe and other neighboring countries and regions, and the days were also handsome. But soon its sights shifted further afield than Eurasia.

No wonder, Israel covers just over 20,000 square kilometers. By 2020, Israel's population will be just over 9.21 million, and its GDP will be about $0.4 trillion, equivalent to 2.5 trillion yuan. Only by opening up to the world can Teva have greater opportunities for development.

Soon, Teva set its sights on the United States. In 1984, the United States introduced the Hatch-Waxman Act, announcing the simplification of generic drug applications. Companies only need to provide corresponding testing evidence to show that their products are bioequivalent to the original drug can submit a marketing application. To address the concerns of generic drug companies, the United States also allows the first company to submit a generic drug application to the FDA to obtain a six-month period of market exclusivity and the right to sell the drug at a price close to the original.

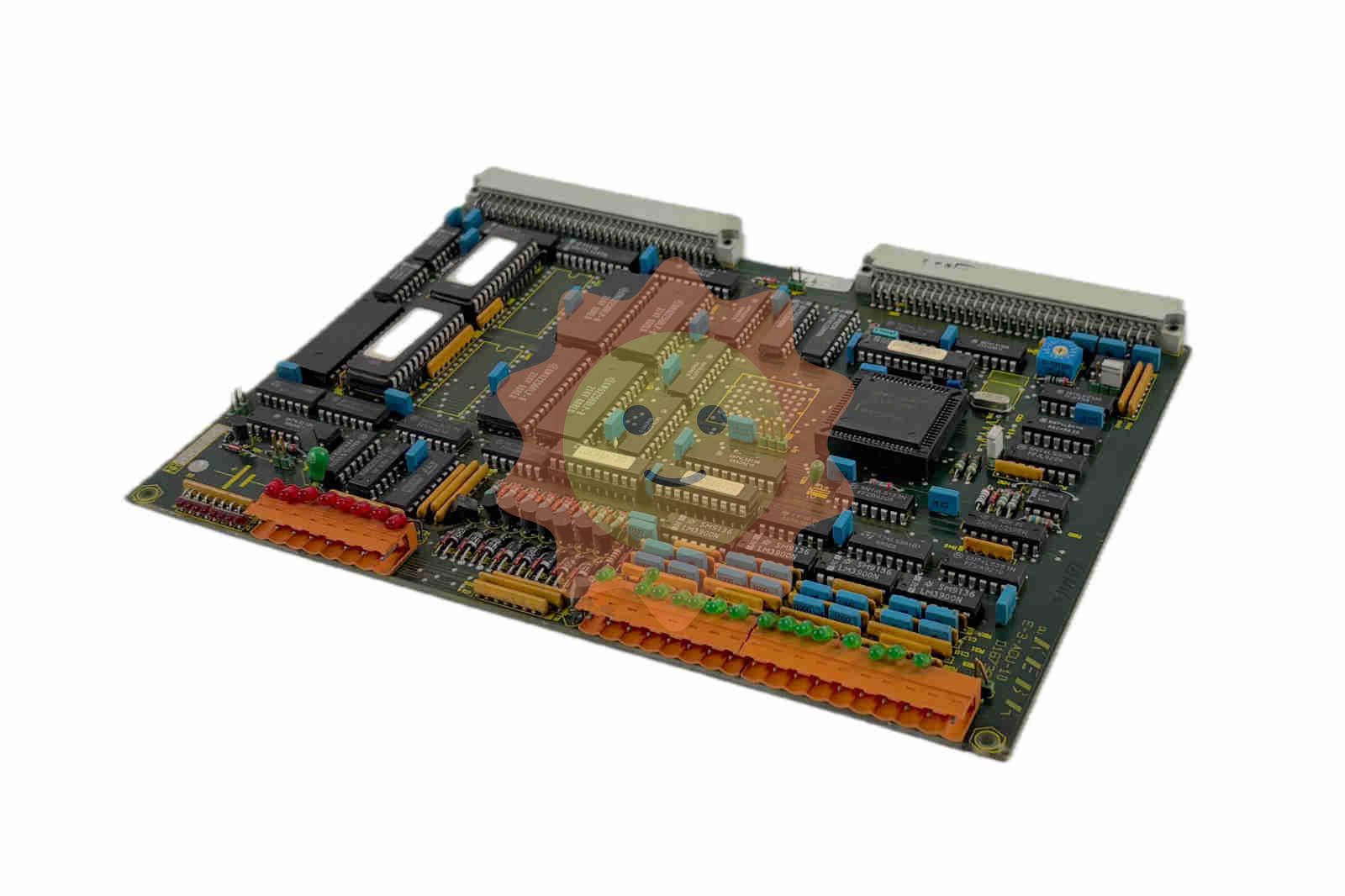

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

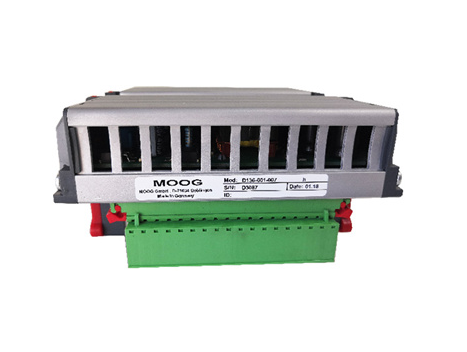

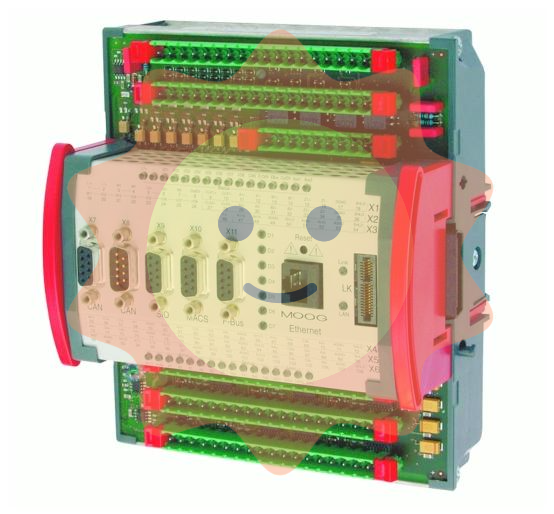

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands