Review the history of life science in China

The development of life science is of great significance to the exploration of the law of life and the revolution of biotechnology. Issues such as food security, clean energy, environmental protection, health and ageing pose new challenges for the life sciences. Many countries in the world have identified life science as a priority development field, in order to promote the development of bioeconomy as a starting point, to achieve sustainable social and economic development. In recent years, with the rapid development of our economy and the continuous growth of national research and experimental development funds, our country has made remarkable achievements in the field of life science. According to the international public report, the number of papers published in the international life science journals in China ranks first in the world, and the citations rank first. In the list of highly cited scientists in the world in 2021 released by Clarivate, China has 935 people selected (excluding data from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan), ranking second in the world. In terms of patented technologies that reflect technological innovation, China's international patents in the field of biotechnology rank second. A number of bio-high-tech companies have entered the world's top 500 enterprises. In the past five years, the number of doctoral and master's graduates has ranked first in the world every year. This huge change has actually been achieved in just 100 years, or the biggest change has occurred in the last 40 years.

Protein & Cell, an international life sciences journal founded in 2010 and based in China, has a special "Memories" column that describes people and events that have made important contributions to the life sciences of our country over the past 100 years. So far, this column has published more than 120 relevant articles, attracting many readers, and opening up a picture for us that our predecessors scientists have worked hard and advanced in spite of wind and rain. More than 40 years of reform and opening up and economic development have provided a strong driving force for the development of life science and technology. When we look back on the history of modern life science in the past 100 years, the cornerstone of the development of life science in our country is still glowing. In order to remember the contributions made by previous scientists to the development of life science in our country, we compiled and published this book. The articles in the book are derived from Recollection columns. In order to give the younger generation of scientists a retrospective understanding of the history of the life sciences in our country, this book focuses on people and events before the 1970s. Due to the limited number of words in the column, each article can only introduce one side of a person or event. Since the original text was published in English, in order to expand the audience, we invited some scientific and technical workers to translate it into Chinese and publish it as a collection. Due to the relatively long history involved, in order to enable the younger generation of scientists to have a comprehensive understanding of this history, understand the development process of China's life sciences, and deeply understand the historical background of specific people and events in a specific period, we have spent a little time in the introduction of this book to make a brief review of the history of China's life sciences.

Before the Opium War, China experienced more than 2,000 years of feudal society, the whole society developed slowly under the old system, and there was a lack of understanding of modern science and technology that arose in the West. For the public, the imperial examination system became the only channel for selecting talents and promoting social ranks. In the middle and late 19th century, if there was any scientific knowledge of modern significance, the popular dissemination in society was mainly the translation and introduction of some western biological works. In 1859, Li Shanlan (an early mathematician) and A. Williamson (Williamson) translated China's first book on the introduction of western modern botany. In 1886, J. Edkins, a British missionary, systematically introduced the preliminary knowledge of zoology, botany and physiology in Chinese based on relevant works. In 1889, Yan Yongjing translated and published American psychologist J. Haaven's Mental Philosophy, which was the first psychological translation in China. The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894 brought unprecedented shock to the Chinese nation. All social strata, deeply ashamed and resentful, began to realize the urgency of changing society and saving the country, and explored various ways to save the country and the people. In 1897, Yan Fu, a famous enlightenment thinker, translated Huxley's "The Evolution of Heaven" and introduced it to China for the first time. The theory of "natural selection and survival of the fittest" promoted the formation of social reform and reform thoughts at that time. The intellectual class began to go abroad to learn science and technology from the West and introduce Western science to China. The abolition of the imperial examination system in 1905 marked the end of the feudal education system. Many intellectuals gave up the path of obtaining fame and fortune through the imperial examinations, opening the channel for the introduction of Western science and technology. Subsequently, our country began to establish modern schools, learn from the west, the rise of natural science education. With the spread of western scientific knowledge, people gradually realize that biology is closely related to people's lives and social needs, and is a basic discipline for developing agriculture, medicine and health, developing resources, and improving people's health. Therefore, biology has been favored by more and more young scholars, who embrace the idea of "saving the country by science" and actively devote themselves to this field.

Studying abroad became one of the main ways to learn natural science from the West at that time. Since 1875, the number of Chinese students studying in Europe, America and Japan has gradually increased. Limited by money and language, most of them studied in Japan in the early days. Since 1909, China has used the Boxer indemnity returned by the United States to fund a group of outstanding young people to study in the United States. According to the agreement between the two sides, in the first four years, China sent no less than 100 students to the United States each year, which kicked off the prelude of a large number of Chinese students to study in European and American universities and research institutions. In 1916, Zou Bingwen received a bachelor's degree in plant pathology from Cornell University in the United States and returned to teach at Jinling University. In 1920, as China's first doctor of biology, Bingzhi returned from the United States. In 1921, Bingzhi established the first modern university biology department built by the Chinese people. In 1922, China's first biological research institution "Institute of Biology, Science Society of China" was established, and Bingzhi was the director. In 1928, Bingzhi and Hu Xianxu led the establishment of the North Calm Biological Survey Institute. The Academia Sinica, founded in June 1928, and the National Beiping Research Institute, founded in September 1929, were the two most important large-scale comprehensive scientific research institutions in China at that time, marking the basic completion of the institutionalization process of scientific research in China. Peking Union Medical College, founded in 1917, was an important institution of biomedical research in China at that time, concentrated a large number of outstanding scientists, and was the key town of experimental biology in China. In the 1930s, China's university departments, research institutions and major branch discipline societies of biological sciences were established one after another, and journals and books were published. In 1937, the development of social economy and technology was interrupted by Japan's all-out war of aggression against China. Due to the war, the brain drain of Peking Union Medical College is very serious.

Pharmacologists Chen Kehui and Xie Heping returned to the United States before and after the Anti-Japanese War, and Wu Xian and Lin Kesheng went to the United States from 1948 to 1949. Many universities and research institutions have moved to Southwest China, and the conditions for running schools and research are extremely difficult. After the end of the Second World War, China's education and scientific research work has been initially restored, in 1948, Academia Sinica selected 25 members of the biological Group and 1 member of the mathematical physics and Chemistry Group (Wu Xian) in the field of life sciences, almost all of them are scholars who returned from studying in Europe and the United States before the outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japan (only Luo Zongluo 1 person studied in Japan). After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, the number of people studying abroad reached a considerable scale. At that time, there were 5,541 overseas students in China, most of whom went abroad from 1946 to 1948, among which the number of students studying in Europe and the United States was the largest, and only the students staying in the United States accounted for 63% of the total number of international students. Students studying life sciences in the United States are mainly concentrated in prestigious universities such as Harvard University and Cornell University. The early returned students overcame difficulties and difficulties in an environment of scarce funds, brought Western scientific knowledge and research methods into China and localized them, established basic scientific research and teaching systems in China, endeavoring to cultivate local talents, and developed science through effective international cooperation. Their work has laid an important foundation for the development of life sciences in China.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China, in the early stage, it mainly sent students to the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, and independently trained various specialized talents in natural science. In the 1950s and 1960s, China sent more than 10,000 students to study in the Soviet Union and more than 1,000 students to study in Eastern European countries. After 1976, higher education and graduate training were restored, and the number of undergraduates and graduate students graduating from higher education institutions increased year by year. The college entrance examination was resumed in 1977, and only 250,000 students out of 5.7 million were admitted. From 1977 to 2017, about 57.6 million undergraduates were enrolled. Since 1995, China has enrolled 7.71 million graduate students. In 1982, only six people in our country received doctorates; In 2002, the number of doctoral degrees awarded that year reached 14,368. From 1987 to 2017, the total number of doctoral graduates reached about 700,000. Since 1978, China has once again launched the program of selecting and sending overseas students. That year, 52 young students were sent to universities and research institutions in the United States, which was the first batch of students to go to the United States after the founding of New China. In 2007, there were more than 350,000 Chinese students studying in American universities and research institutions. In 1979, American physicist and Nobel Prize winner Professor Lee Zhengdao initiated the China-United States Physics Examination and Application Program (CUSPEA Program). Every year, more than 100 Chinese students are selected to study physics at leading universities and research institutions in the United States. Then Rui Wu, an American molecular biologist and professor at Cornell University, launched the China-United States Biochemistry Examination and Application Program (CUSBEA program). The program, which began in 1982 and ended in 1989, sent 422 students in eight classes. At the same time, domestic education and scientific research have also been rapid development, training a large number of local scientists. Especially in the last 20 years of the 20th century, the locally trained scientists, under the conditions of poor scientific research conditions and lack of scientific research funds, assumed the heavy responsibility of revitalizing the motherland's science and technology. Their contributions largely filled the gap between generations of research and education teams at that time, and laid the foundation for China's life science research to catch up with the world's advanced level. In the 21st century, a large number of students have returned to their motherland to join the education and science and technology careers. Funding for scientific research and development increased somewhat before the 1990s, but the total amount remains low. Even in 1990, the national R&D expenditure was only 12.5 billion yuan. However, by 2018, China's investment in research and experimental development reached 2 trillion yuan, ranking second in the world. To be precise, the earth-shaking changes in China's life science should be attributed more to the last 40 years. However, the rapid development of these 40 years is the result of the hard work of senior scientists in the past nearly 100 years.

This book introduces a group of pioneers and founders of modern life sciences in China, who may be unfamiliar to many young people today, such as Bingzhi, founder of modern biology and zoology; Wu Xianwen, founder of zoology; Hu Xiansu and Qian Chongshu, founder of botany; Dai Fanglan, founder of microbiology; Bei Shizhang, founder of cell biology; Wu Liande, founder of medicine; Famous scientists include Lin Kesheng, founder of physiology, Wu Xian, founder of biochemistry, Xie Heping, pioneer of pathology, Chen Kehui, founder of pharmacology, Chen Zhen, founder of genetics, and Zou Bingwen, founder of agronomy. Most of them studied overseas in their early years, and made important contributions to their respective research fields after returning to China, becoming the founders of modern life science and various sub-disciplines. Many of the students they trained became leading figures in the life sciences of our country in the second half of the 20th century.

Readers can also learn from this book about the outstanding achievements of China's modern life sciences, which have important international influence. For example, Wu Liande's discovery and use of scientific methods to defeat pneumonic plague is still relevant to public health today, more than 100 years later. Tang Feifan was the first to discover the pathogen that causes trachoma - chlamydia trachoma, which solved the epidemic disease that seriously threatens the world's eye health. Tong Zhou established nuclear transfer technology and bred the world's first group of cloned fish. Gu Fangzhou developed and produced polio vaccine, which eliminated polio in China, becoming another initiative in the history of world public health after the eradication of smallpox. Wang Yinglai and other researchers from three units worked together to achieve the first complete synthesis of crystalline bovine insulin in 1965. Debao Wang and other scientists spent 13 years to complete the artificial synthesis of yeast alanine transfer ribonucleic acid (yeast alanine tRNA), and its composition, sequence and biological function are exactly the same as the natural yeast alanine tRNA. Tu Youyou was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015 for discovering artemisinin in 1971, which can treat malaria. In 1999, Chinese scientists participated in the Human Genome Project, and later scientists from six countries published the completed map of the project.

The book also introduces some important events in the history of modern life science development in China, such as the debate between descriptive biology and experimental biology in the 1930s, the important turning point of genetics - the Qingdao Genetics Symposium in 1956, and the establishment of the Sino-Japanese joint laboratory. At the same time, readers can also learn about the origin of famous universities such as Harvard University and Cornell University with China's modern life science, as well as the enthusiastic help of some international friends for China's life science cause. For example, the American biologist Qi Tianxi has worked and lived in China for several decades, and promoted the development of biology in China in the aspects of biological education, animal and plant investigation, and biological research establishment. James Watson, the "father of DNA", invited Chinese scholars to visit Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and made great efforts and contributions to the establishment of Cold Spring Harbor Asia.

Reviewing history is to explore the future. "Scientific achievements cannot be separated from spiritual support", which has been fully confirmed in the early scientists. In the extreme predicament of social turmoil and constant war, they have made great efforts to develop the life science cause of the motherland and achieved outstanding achievements. What supports them is the earnest love for national conditions and firm belief of "saving the country scientifically". Reviewing the development history of life science in our country has important enlightenment for us to pursue the path of talent growth, explore the law of scientific and technological development, and international cooperation and communication. Therefore, the scientific research workers of our new era should inherit the scientific spirit of the older generation of scientists and strive to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

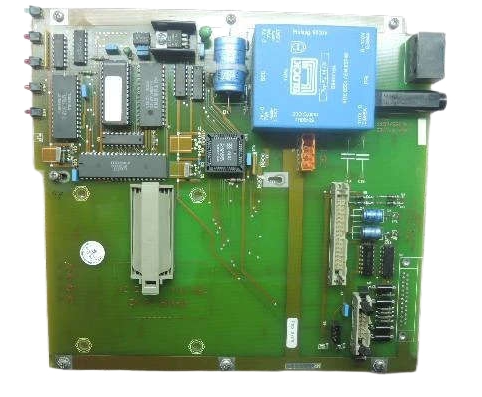

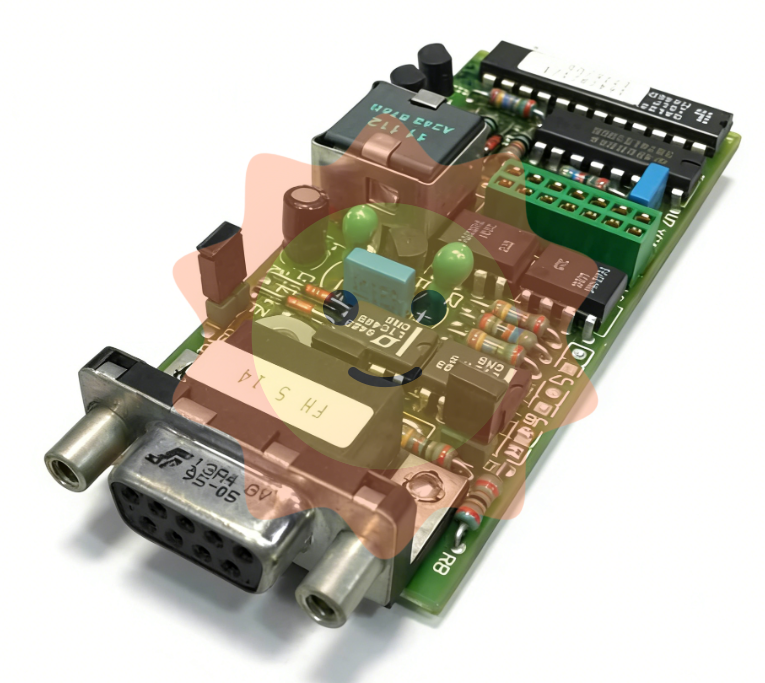

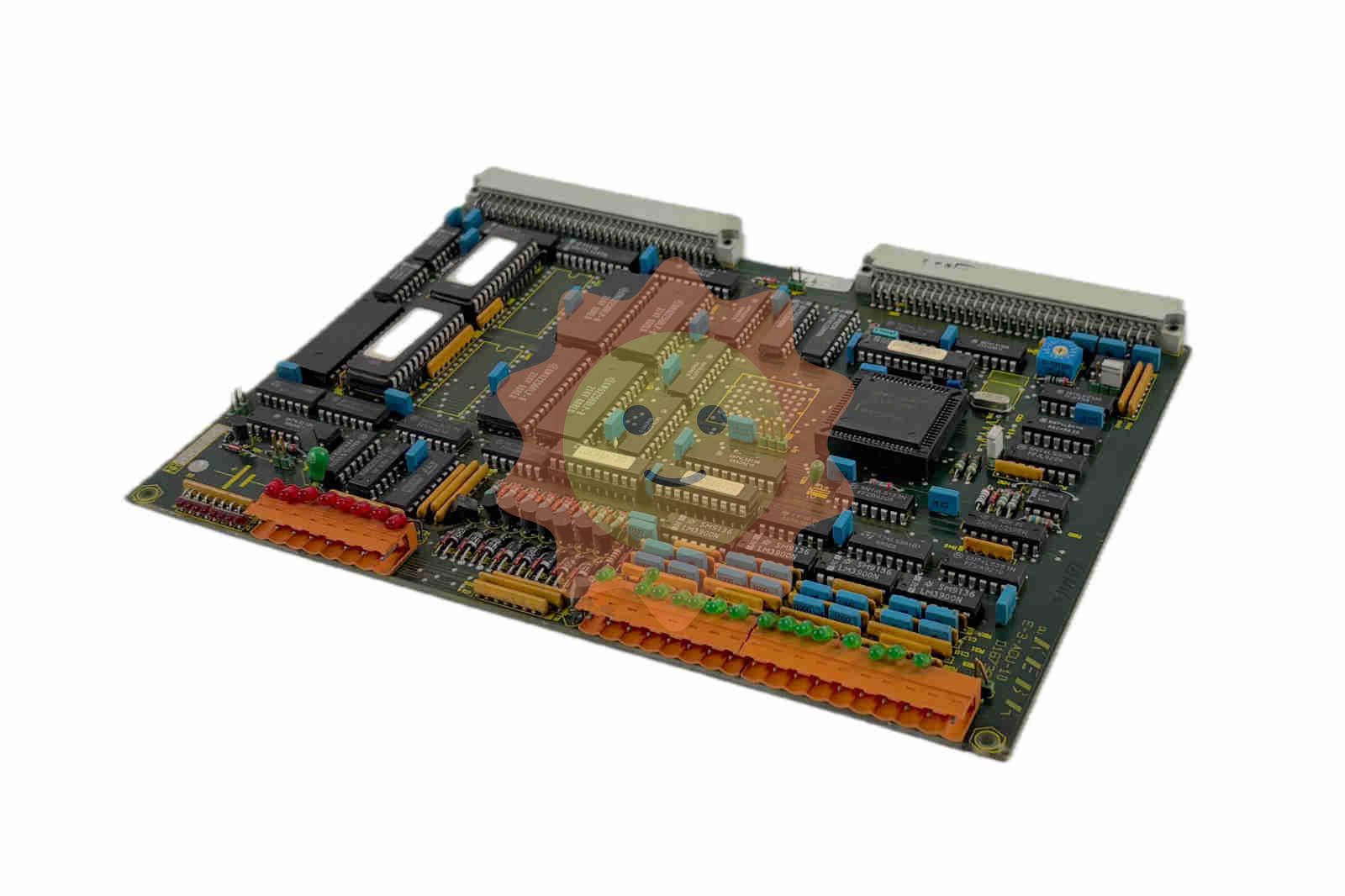

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

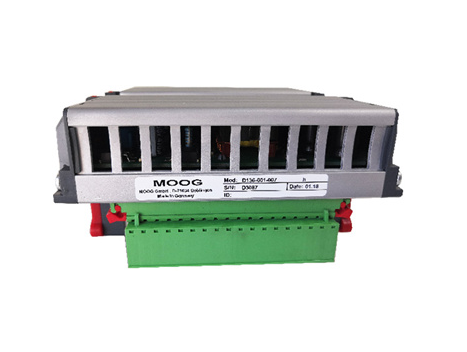

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands