Electrons can "fission" and release photons to obtain recoil

The third section of electrons can "fission" to release photons to obtain recoil

For the nuclei and free electrons in the free state, one with positive charge and the other with negative charge, they will inevitably attract each other only under the action of electrostatic force. As the distance between the free electrons and the nucleus continues to shrink, the electrostatic attraction of the free electrons will also increase rapidly, which inevitably leads to the internal binding force of the free electrons being insufficient to resist the tearing effect of the electrostatic attraction of the nucleus at some point. At this time, the electron will "fission" release the photon, and after the electron fission releases the photon, its mass decreases and the recoil effect of the photon is obtained, and the internal binding force rapidly increases, which can resist the tearing effect of the electrostatic gravity of the nucleus. Therefore, after the first "fission" of the free electron, it will move to a stable orbit far away from the nucleus and stay in this orbit under the reaction of the photon. Since electrons have only a few specific "magic mass numbers", there is only one way to release photons from the free electron to the first fission, and the free electron must be in the position of the "magic mass" of the internal binding force after fission (because other masses of electrons are unstable).

When the electrons that have undergone "fission" are subjected to the disturbance of the nucleus again and continue to get close to the nucleus, as the distance between the electrons and the nucleus continues to decrease, it will inevitably lead to the enhancement of the electrostatic gravitational tearing effect of the nucleus. When the internal binding force of the electrons is less than the electrostatic gravitational tearing effect of the nucleus at some point, The electrons will split again, release photons, lose mass and recoil again, and the internal binding force will increase rapidly... In the process of electron close to the nucleus, the electron may undergo several "fission", each "fission" after the internal bonding force of the electron will increase, the mass will decrease. Because the electrostatic attraction of the nucleus always reduces the fission mass of the electron, the closer the electron to the nucleus the greater the electrostatic attraction, the greater the possibility of the electron deformation and release of photons, so the same electron in its stable state, the closer the mass from the nucleus, the smaller the mass, the greater the mass from the nucleus, of course, the mass of the free state of the electron is the largest.

The magnetic interaction between the electron and the nucleus provides the angular velocity for the electron to rotate around the nucleus

Macroscopic point charges must not be able to form atom-like systems. In the macro, if two particles with dissimilar charges start at a certain distance apart, assuming that they are not acted on by other external forces, no matter what their mass and how much electricity they carry, they will attract each other along a straight line under the action of electrostatic force, and will not form an atom-like system in which one point charge rotates around another point charge.

An electron needs an angular velocity to move around the nucleus. It has been pointed out that an electron needs a certain angular velocity to rotate around the nucleus, and where does this angular velocity come from? In fact, this problem was considered as early as hundreds of years ago when Newton studied the motion of planets around the sun. Newton began to think about the formation of the solar system after discovering the gravitational force. He believed that God pushed the formation of the solar system at the beginning of its formation, which led to the formation of the solar system. Newton called this push the "first push of God" or called the "hand of God", Newton firmly believed in the existence of the "hand of God", and thus slipped into the study of theology in his later years, it is a pity.

Usually the magnetic force between wires. The physicist Ampere found that the energized wire will generate a magnetic field in the space around it, and the magnetic field direction generated by the different current direction is not the same, and the magnetic field generated by the energized wire can be determined by the right hand rule. If two energized wires are close enough, the magnetic fields formed by the two energized wires will influence each other: two parallel wires with current in the same direction will attract each other, and two parallel wires with current in opposite directions will repel each other. If the two parallel wires are not energized (there is no current inside), they will not affect each other. This discovery has implications for our study of atomic systems.

Assuming that the nucleus and the electron are at a certain distance apart and at rest with each other at the beginning, they will rapidly approach each other under the action of electrostatic acceleration, and the nucleus and the electron moving in opposite directions are equivalent to two parallel wires passing through the same direction of the current, they will have a magnetic effect and attract each other, and the greater the relative speed of the nucleus and the electron, the greater the magnetic effect. Thus: under the action of electrostatic gravity, the nucleus and the electron are close to each other, and under the action of magnetic force, the nucleus and the electron begin to rotate around each other, and eventually the nucleus and the electron are close to each other along the helix and form a stable atomic system in which the electron rotates around the nucleus. Here we see that because the magnetic force between the nucleus and the electron provides the initial velocity of the electron's rotation around the nucleus, the electrostatic force between the electron and the nucleus will attract them together in a straight line, and the magnetic force between the electron and the nucleus will rotate them around each other and eventually form the atomic system. Since the charge-mass ratio of the macroscopic charged particles is much smaller than that of the electron and the nucleus (how many orders of magnitude smaller can be calculated by interested friends), the speed of the macroscopic charged particles moving towards each other under the action of electrostatic force is very small, and the resulting magnetic force is insignificant enough to affect the motion of the macroscopic charged particles. So normally, macroscopic charged particles are attracted to each other in straight lines.

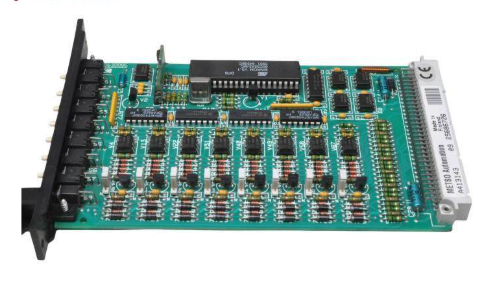

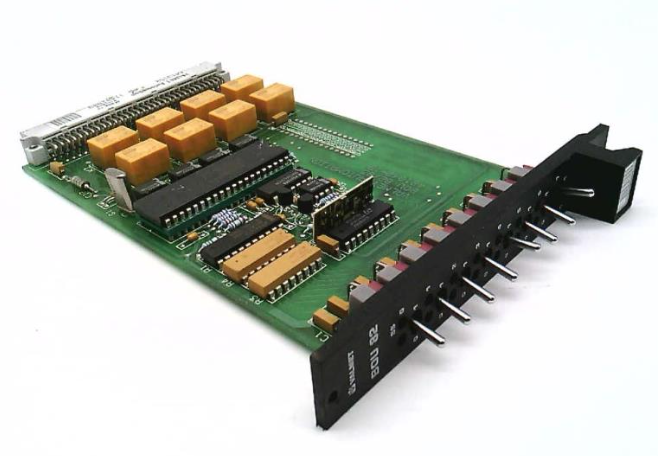

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

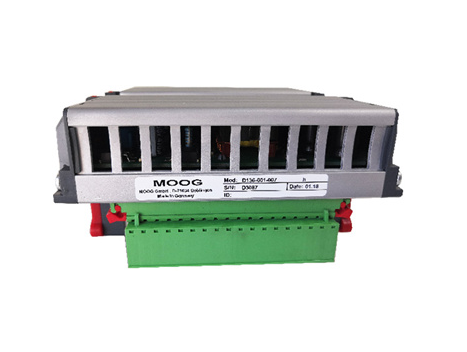

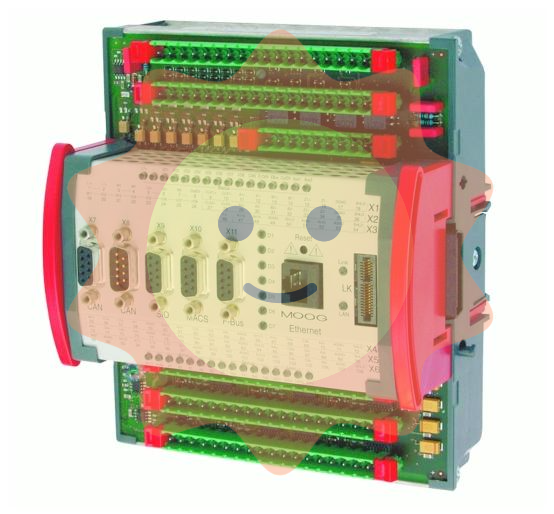

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands