A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas

About this report

Measures implemented this year could bring down gas imports from Russia by over one-third, with additional temporary options to deepen these cuts to well over half while still lowering emissions.

Europe’s reliance on imported natural gas from Russia has again been thrown into sharp relief by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February. In 2021, the European Union imported an average of over 380 million cubic metres (mcm) per day of gas by pipeline from Russia, or around 140 billion cubic metres (bcm) for the year as a whole. As well as that, around 15 bcm was delivered in the form of liquefied natural gas (LNG). The total 155 bcm imported from Russia accounted for around 45% of the EU’s gas imports in 2021 and almost 40% of its total gas consumption.

Progress towards net zero ambitions in Europe will bring down gas use and imports over time, but today’s crisis raises specific questions about imports from Russia and what policy makers and consumers can do to lower them. This IEA analysis proposes a series of immediate actions that could be taken to reduce reliance on Russian gas, while enhancing the near-term resilience of the EU gas network and minimising the hardships for vulnerable consumers.

A suite of measures in our 10-Point Plan, spanning gas supplies, the electricity system and end-use sectors, could result in the EU’s annual call on Russian gas imports falling by more than 50 bcm within one year – a reduction of over one-third. These figures take into account the need for additional refilling of European gas storage facilities in 2022 after low Russian supplies helped drive these storage levels to unusually low levels. The 10-Point Plan is consistent with the EU’s climate ambitions and the European Green Deal and also points towards the outcomes achieved in the IEA Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Roadmap, in which the EU totally eliminates the need for Russian gas imports before 2030.

We also consider possibilities for Europe to go even further and faster to limit near-term reliance on Russian gas, although these would mean a slower near-term pace of EU emissions reductions. If Europe were to take these additional steps, then near-term Russian gas imports could be reduced by more than 80 bcm, or well over half.

The analysis highlights some trade-offs. Accelerating investment in clean and efficient technologies is at the heart of the solution, but even very rapid deployment will take time to make a major dent in demand for imported gas. The faster EU policy makers seek to move away from Russian gas supplies, the greater the potential implications in terms of economic costs and/or near-term emissions. Circumstances also vary widely across the EU, depending on geography and supply arrangements.

Reducing reliance on Russian gas will not be simple, requiring a concerted and sustained policy effort across multiple sectors, alongside strong international dialogue on energy markets and security. There are multiple links between Europe’s policy choices and broader global market balances. Strengthened international cooperation with alternative pipeline and LNG exporters – and with other major gas importers and consumers – will be critical. Clear communication between governments, industry and consumers is also an essential element for successful implementation.

Encourage a temporary thermostat adjustment by consumers

Many European citizens have already responded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in various ways, via donations or in some cases by directly assisting refugees from Ukraine. Adjusting heating controls in Europe’s gas-heated buildings would be another avenue for temporary action, saving considerable amounts of energy.

The average temperature for buildings’ heating across the EU at present is above 22°C. Adjusting the thermostat for buildings heating would deliver immediate annual energy savings of around 10 bcm for each degree of reduction while also bringing down energy bills.

Public awareness campaigns, and other measures such as consumption feedback or corporate targets, could encourage such changes in homes and commercial buildings. Regulations covering heating temperatures in offices could also prove to be an efficient policy tool.

Impact: Turning down the thermostat for buildings’ heating by just 1°C would reduce gas demand by some 10 bcm a year.

Step up efforts to diversify and decarbonise sources of power system flexibility

A key policy challenge for the EU in the coming years is to scale up alternative forms of flexibility for the power system, notably seasonal flexibility but also demand shifting and peak shaving. For the moment, gas is the main source of such flexibility and, as such, the links between gas and electricity security are set to deepen in the coming years, even as overall EU gas demand declines.

Governments therefore need to step up efforts to develop and deploy workable, sustainable and cost-effective ways to manage the flexibility needs of EU power systems. A portfolio of options will be required, including enhanced grids, energy efficiency, increased electrification and demand-side response, dispatchable low emissions generation, and various large-scale and long-term energy storage technologies alongside short-term sources of flexibility such as batteries. EU member states need to ensure that there are adequate market price signals to support the business case for these investments.

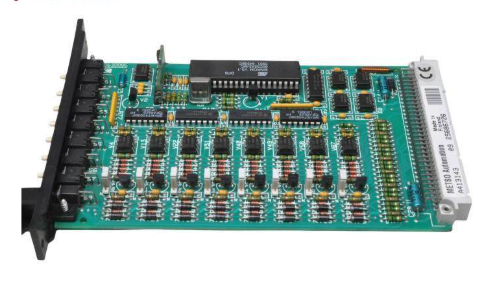

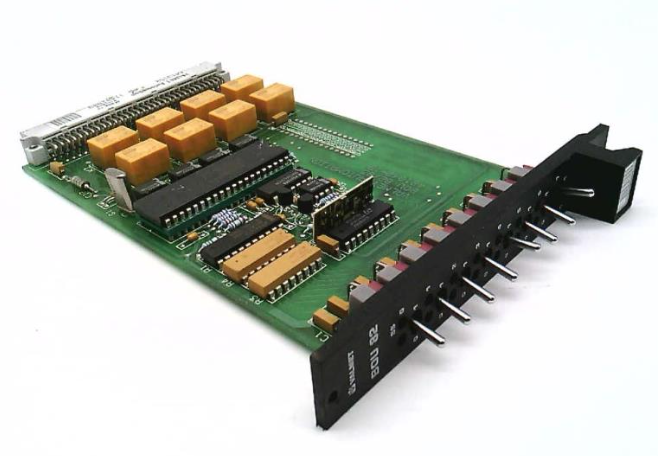

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

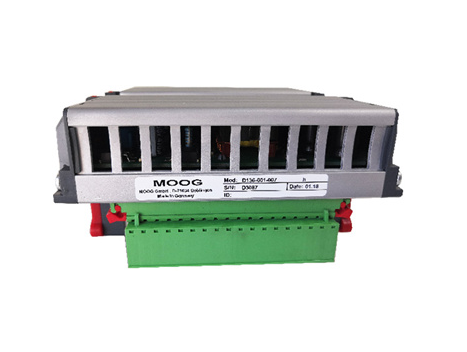

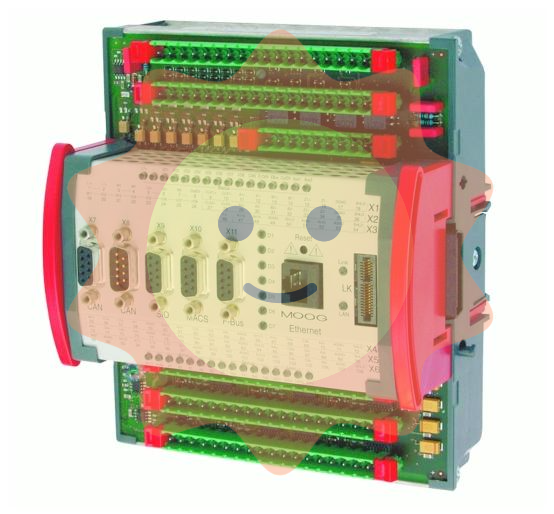

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands