Electricity security matters more than ever

The potential indirect impacts of blackouts are also enormous and include: transport disruption (the unavailability of trains and charging stations for electric vehicles), food safety issues (risk to the cold chain), problems related to public order (crime and riots), and loss of economic activity. This can lead to health and safety problems as well as substantial financial losses. In extreme cases where power outages relate to extreme natural events, loss of electricity supply exacerbates other recovery challenges, making restoration of the power system one of the earliest priorities.

Load shedding is the deliberate disconnection of electrical power in one part or parts of a power system. It is a preventive measure taken by system operators to maintain system balance when supply is currently or expected to be short of the amount needed to serve load plus reserves, after exhausting other options like calling on demand response, emergency supplies and imports. These are short-duration events lasting from minutes to a few hours where small amounts of energy are rationed to segments of consumers (1% to 2% of the unserved energy during a cascading blackout), while allowing loads that provide essential services to continue to be served. They are, from a consumer point of view, indistinguishable from other interruptions on the distribution grid. The anticipated, controlled and limited use of this extreme measure should be seen as an instrument to maintain security of supply.

Most current reliability standards target a level of supply that would expect a small amount of acceptable load shedding as a way to balance security of supply and economic considerations. For example, the Alberta system operator in Canada has needed to apply this type of interruption in three events between 2006 and 2013, with a total duration of 5.9 hours and an amount of energy well below the regulatory (reliability) standard. Even if load shedding results only in small amounts of energy not being served, it completely cuts power supply to certain groups of customers, creating an array of inconveniences. To share the damage and minimise the inconvenience, the power cuts are often “rolled”, switching from one customer block to the next. In the near future, digitalisation should allow power systems to phase out this small but drastic and inefficient way of rationing energy. This would cut energy only to non-essential appliances or storage-enabled devices, and maintain it for other uses where interruption would create more inconvenience, such as lifts.

Long rationing periods of electricity occur when system operators and governments have to limit power supplies on a planned basis because of large deficits of electricity supply to meet demand. This is possibly the most harmful type of power sector event that a society can face. Some long-duration rationing events have meant rationing as much of 4% to 10% of annual electricity consumption, creating large social and macroeconomic impacts. They include the one in Brazil in 2001 due to drought and an unsuitable investment framework. The large supply shock in Japan following the Great East Japan Earthquake also belongs to this category, when the government responded with a nationwide electricity conservation campaign that forced industry to make massive electricity demand shifts.

Many emerging economies such as Iraq and South Africa see their economic and social welfare severely impacted by recurrent periods of electricity rationing that can last many months. Although developed economies have solved this type of event due to sound investment frameworks, it remains a challenge for many developing economies. Nonetheless, developed economies should not take for this dimension for granted; investment frameworks need to be updated and resilient to new trends.

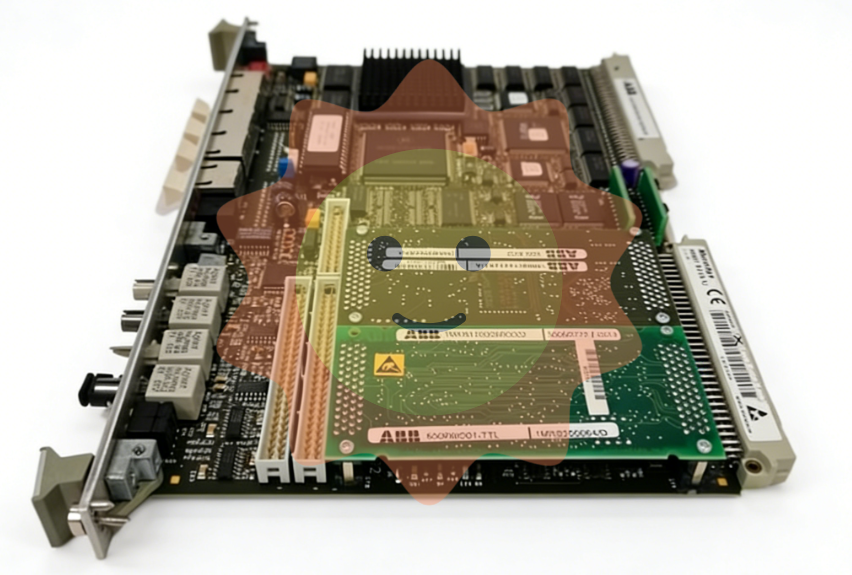

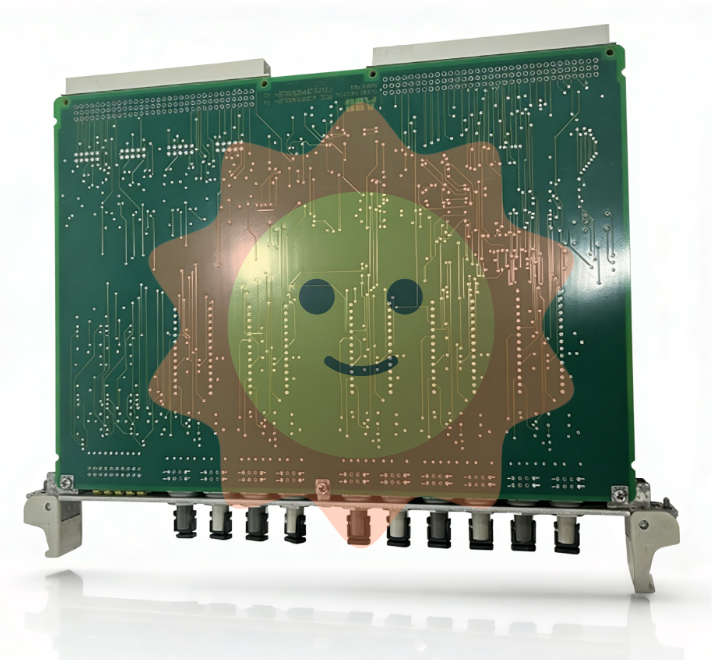

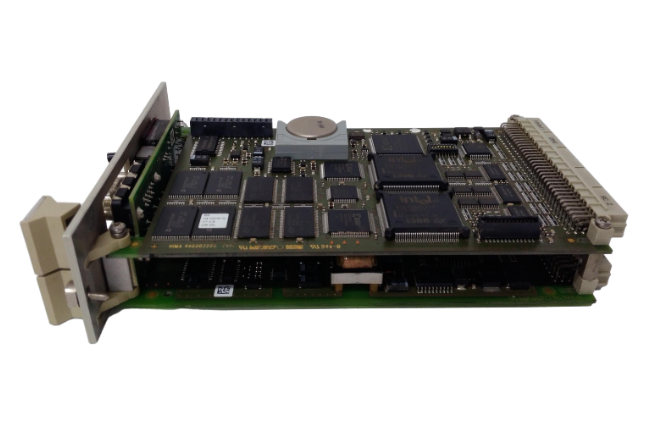

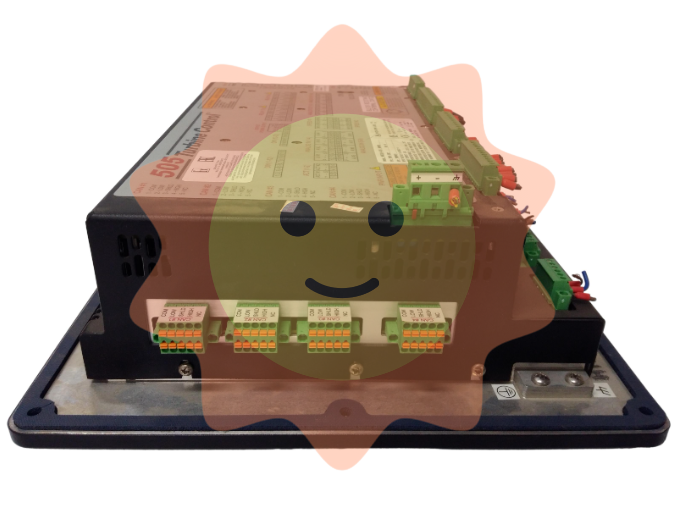

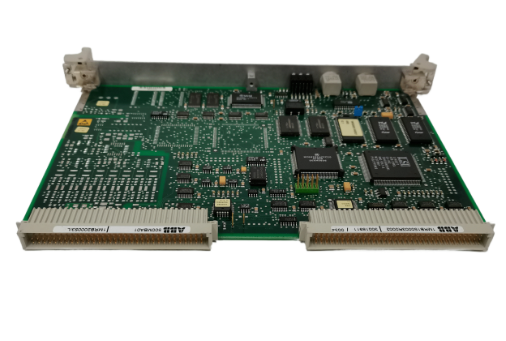

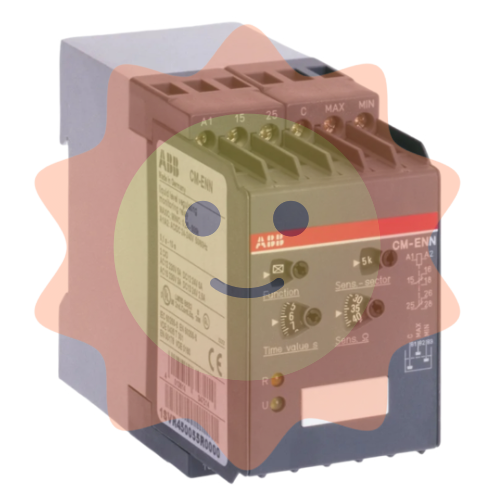

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA