Tracking e-commerce company Amazon, the nonfiction drama "Fulfilling the Order" shows people's lives under the influence of the tech giant

At present, online shopping has become a necessary skill for each of us, with the popularity of smart phones, more and more consumers have changed their shopping habits, choosing to buy goods and services online. People can easily understand tens of thousands of goods through various online shopping platforms, compare their prices and quality, and the next day they can go home with the touch of a finger.

For the increasingly convenient online shopping, American journalist Alec McGillis has done more in-depth research, he spent more than ten years to investigate the world's largest online shopping platform Amazon, and online shopping industry chain upstream and downstream of different people to talk, written a non-fiction book "The Order: Everything and Nothing." Through Amazon, this book shows the significant impact of online shopping patterns on society. Recently, the simplified Chinese version of this book was introduced by the New Classic Culture.

Amazon (AMZN) has announced that it will stop operating its Kindle e-bookstore in China on June 30, which means that the company has basically withdrawn from the Chinese market.

Despite losing ground in China, the company, founded in 1994, remains one of the world's largest online retailers and providers of cloud computing services. In the United States in particular, Amazon dominates its retail sector. At the same time, Amazon has created a large number of jobs in the United States, as the second largest private employer in the United States, its logistics centers, distribution centers and data centers and other facilities, providing jobs for hundreds of thousands of people.

However, Amazon's outsize influence has also generated some controversy. Some people are concerned about its impact on the traditional retail industry and market monopoly, and some people question its tax strategy and harsh labor conditions. The book is journalist Alec McGillis's comprehensive examination and dissection of the company, exploring the social, economic and political implications of Amazon's expansion in the United States. The book delves into Amazon's labor model and labor conditions, and their impact on American communities, focusing on Amazon's monopoly position in American retail, and using it as a lens to show an America that is divided geographically and hierarchically by capital.

In order to show a different perspective of Amazon, the author Alec McGillis visited many cities and towns in the United States, interviewed drivers, delivery workers, sorters, manufacturers and other ordinary people at different positions in the industrial chain, and also delved into the world of activities of politicians, lobbyists, and corporate executives, and wrote about the diverse life under the Amazon empire with wonderful nonfiction techniques. And with real data and sociological perspectives to show the huge rift in social division.

The Los Angeles Times praised that reading the book was like watching The American TV series The Wire, "Only skilled journalists can weave data and anecdotes together so effectively."

By moving geographically from the political center of Washington to the industrial town, the book takes a top-down scan of America's first-tier cities and towns, focusing on the company's enormous impact on small businesses, the real estate market, the employment environment, and the news industry.

In the author's book, Amazon is not just a company, but a revolutionary business model in which everyone is involved. Online shopping has brought the convenience of "one-click order", but also brought a series of chain reactions: the real economy continues to decline, traditional communities have fallen; Small and medium-sized retailers face unfair competition; Labor is trapped in a demanding efficiency system. The era of e-commerce economy is coming, and businesses, workers, and buyers are all spared. Through this book, the author shows how algorithms dominate life and how capital invades everyday life.

After publication, the book was recommended by many media in the United States, including the New York Times, The Financial Times, The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Times Literary Supplement and American Public Radio. At the same time, the book has been translated into many languages, sparking a global discussion about Amazon and online shopping.

Although Amazon has pulled out of China, the company and its impact still have important implications for us across the ocean.

From the perspective of the drawbacks of the Internet, "Fulfilling the Bill" describes the collective dilemma of the contemporary people. As the subtitle of this book, "All things and Nothing," suggests: We live in an age of all things, trapped in a life of almost nothing; We get 30-minute take-out, next-day delivery, and the convenience of seven-day returns for no reason, but lose the dignity of labor, the freedom of choice, the right to public participation, and the connection and humanity that once existed in the neighborhood.

As the authors say in the book, not many people are crying over the loss of a sea of parking lots and a food court with no Windows. But it's not just malls and plazas that are gone, it's the crowds, communities, and opportunities for face-to-face conversation that once thrived.

Read some chapters

Hector Torres was asked by his wife to move into the basement. There's nothing wrong with him, let alone cheating in his marriage. He just didn't have the right job.

Ironically, if his wife hadn't pushed him, Hector wouldn't have taken the job. Hector was unemployed for 11 years when he lost his $170,000-a-year tech job during the Great Recession. More than 50 years old, was always favored young and energetic industry abandoned, people in the trough, Hector depressed, depressed. The family lives off the income his wife Laura earns from selling training courses on medical diagnostic equipment. In 2006, unable to afford a $5,500 monthly mortgage, Hector and his family fled the San Francisco Bay Area and moved to a larger house in suburban Denver, Colorado.

Then Laura gave her long-unemployed husband an ultimatum: If he couldn't find a job, he had to leave. So he returned to California to join his family. Hector comes from an immigrant family and came to California from Central America decades ago. His sister, who lives in the outer suburbs of San Francisco, took him in. If he plans to go out, he must be back before 8:30 p.m., otherwise he will disturb his brother-in-law's rest. The brother-in-law wakes up at 4:30 a.m. and drives to Silicon Valley before dawn, spending more than three hours a day commuting like 120,000 other Bay Area workers.

After five months of this, Laura found a way for her husband to return home, but he had to find a job. Hector did eventually find a job, but that was in June 2019, six months later. Once, he drove past a warehouse, saw a job Posting, stopped and asked, and they told him to report for work the next day.

Hector works four all-nighters a week, usually from 7:15 p.m. the night before to 7:15 a.m. the next. His rush around the warehouse -- loading out trailers, unloading them on pallets, sorting envelopes and packages -- meant that he spent the night standing at conveyor belts (there were no chairs in the warehouse), moving hundreds of items an hour from one belt to another, carefully positioned so that the side with the bar code faced up for scanning machines.

There was a huge pile of boxes waiting to be moved, some weighing as much as 50 pounds - weight was secondary, and the real problem was that until the boxes were lifted, it was impossible to tell whether they were light or heavy by their size alone. This unpredictable situation is a constant challenge for the body and mind. For a while, Hector wore a waist guard, but it was too hot to wear, like being roasted on a fire. He also developed tendinitis in his elbow. Each shift, he often walked more than 12 miles - according to the smart bracelet - he thought the bracelet must be broken, bought a new pedometer and wore it, and the reading was the same. Apply topical pain relief cream before work, take ibuprofen at work, stand on an ice pack when you get home, put a cold compress on your elbow, and soak your feet with Epsom salt. Shoes should be changed frequently to disperse the stress on the sole. Hector makes $15.60 an hour, a fifth of what he made when he was in the tech industry, and far better than being unemployed.

The warehouse, located in Thornton, 16 miles north of Denver, only opened in 2018. Clint Autry, the warehouse's general manager, has been with the company for seven years and has helped open many other facilities across the country. He has even been involved in testing radio-wave vests that keep fully automated "colleagues" alert when workers have to step into the path of "drive unit" robots in warehouses that move large loads. "Our key mission is to get products to customers in the fastest and most logistically cost-effective way," the general manager said during a presentation at a large open house at the Thornton Warehouse.

Since mid-March 2020, as COVID-19 lockdown measures have taken hold, the Thornton warehouse's total business has climbed, as it has across the country. Millions of Americans feel the only way to stay safe is to shop online from home, and orders are surging to holiday levels. Hector had only been on the job for nine months, and he was the only one of the 20 people who had gone through the orientation with him - the others either had trouble adjusting to the pace, suffered an injury, or ran out of time off after an injury and were laid off. Now, the pressure of a surge in orders, coupled with fears of close contact in warehouses amid the pandemic, is making the movement of people more frequent. The number of workers is shrinking, putting more pressure on those who remain. Hector was required to work overtime -- 12 hours a day, five days a week. With longer hours and fewer days off, Hector's tendinitis got worse.

He learned about the situation of the workers with whom he was in close contact and worked every day - the company did not say anything, but heard it from other workers. One day, the 40-something co-worker stopped showing up for work, and Hector thought he was one of those people who quit, because so many people just leave. But then it was said that the colleague had actually contracted the virus and was seriously ill. When Hector told his wife all this, Laura was worried about the health of her family, especially her elderly mother, who lived with them and suffered from a blocked lung. So Laura asked her husband to move into the basement. The basement wasn't much renovated, but they put a bed for Hector, equipped with a mini refrigerator, microwave, and coffee maker. To use the bathroom, he had to sneak upstairs.

What annoyed Laura was that they had all figured it out on their own, that the company had not informed Hector of anything. Nor did the company tell you how to deal with the risk of contagion. There is no public service hotline to consult. Laura tried looking online for instructions on how to deal with the situation, and the only thing she could find were the company's web pages boasting about what it had done as a company to cope with the coronavirus crisis. "They may have done a lot," she said, but the company "has profited off its employees every step of the way without giving them and their families the protection they deserve."

She could not help regretting that she had not rushed Hector to work there. "They call themselves a technology company, but they're really a sweatshop," Laura said. "This company controls our economy and our country."

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

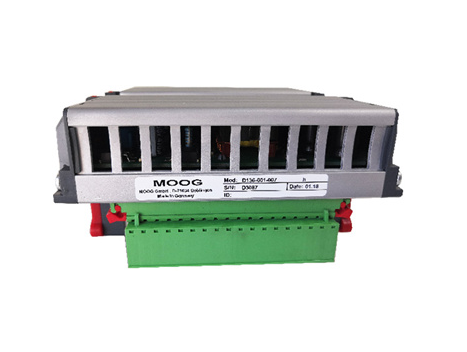

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA

- Other Brands