Digitalisation will come to the fore

The energy transition will change the diversity of every power system – changing their vulnerability to shocks

Until now, wind and solar PV have contributed positively to diversity in the generation mix. They are indigenous resources, which have therefore helped fuel-importing countries reduce their import bills and increase their self-sufficiency. A well-diversified generation mix, with contributions from wind and solar PV, can improve electricity security by mitigating risks arising from physical supply disruptions and fuel price fluctuations. Small-scale generators, such as distributed wind and solar PV, also have the potential to facilitate recovery from large-scale blackouts during the restoration process, while large thermal power plants take longer to resume normal operations since they need a large part of the system to be restored. These are clear examples of electricity security benefits from increasing the share of wind and solar PV. For example, in the People’s Republic of China, a shift from a strong reliance on coal to increased wind and solar will increase the diversity of the generation mix out to 2040.

Looking ahead, electricity supply systems in some regions could see less diversity in power generation sources. European electricity markets have achieved a high level of interconnection between power systems across many countries. They are endowed with diverse power generation sources, including natural gas, coal, nuclear, hydro, wind, solar PV and other sources. Such generation fuel diversity has been a source of confidence in electricity supply security spanning a wide region. As some generation sources are likely to decline in capacity, the diversity of the future system will need to be found in a low-carbon generation mix, flexibility in supply and demand response, and the ever-increasing importance of grid interconnections.

Coal-fired power plants, in particular, are being decommissioned to align with ambitions to reduce CO2 emissions and pollution levels. The trend will need to continue in order to achieve climate change mitigation objectives, increasingly supported by policy measures and finance strategies to phase out the use of coal-fired generation.

Many other electricity systems today also have quite a diverse generation mix, with natural gas, coal, nuclear, hydro, biomass, wind and solar PV. A further increase in VRE combined with a decline in conventional generation will require a review of electricity security frameworks by policy makers, supported by input from the wider industry. VRE and other flexibility sources such as demand response and energy efficiency provide an important contribution to adequacy. Fully incorporating these resources into a reliability framework and optimising them in system operations calls for strengthened analysis and appropriate regulatory and market reforms. Early steps in the clean energy transition of particular regions provide critical lessons for those still in an initial phase of their own transition. For the advanced regions, implementation of the next steps is likely to be more challenging than those already achieved.

The significant concentration of low-carbon generation in a few VRE sources, such as onshore wind and PV, will create increasing challenges for policy makers, regulators and system operators. For example:

Tapping into a larger set of variable resources with different generation patterns will reduce these underlying challenges by smoothing the combined VRE output over time, which can both decrease the economic cost of decarbonising the system and soften the integration challenges associated with few generation sources. For instance, solar and wind generation often exhibit both diurnal and seasonal complementarity, reducing the overall variability of VRE output across the day as well as through the year.

For Europe, the growing prospects of offshore wind are a promising opportunity to further diversify the low-carbon mix, as larger capacity factors and complementary generation patterns will soften the integration challenges of VRE. Still, in highly decarbonised systems with diminished nuclear and fossil fleets, other low-carbon sources such as biomass, biogas, hydrogen and carbon capture, use and storage will eventually be needed to cover periods of low VRE generation, together with new flexibility sources such as power storage and the increasing scope of demand-side response.

Lower than needed levels of investment in power systems today present risks for tomorrow

Although wind and solar PV have seen impressive growth in recent years, overall spending in the power sector appears to be less than what will be needed to meet forthcoming security challenges. To this end, the IEA World Energy Investment Report 2020 portrays a rather grim picture. Global investment in the energy sector declines by 20% or USD 400 billion in 2020 in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis. The oil and gas upstream sectors see the largest negative impact compared to the electricity sector. Nevertheless, the overall level of investment in power in 2020 declines by 10%. The crisis is prompting a further 9% decline in estimated global spending on electricity networks, which had already fallen by 7% in 2019. Alongside a slump in approvals for new large-scale dispatchable low-carbon power plants (the lowest level for hydropower and nuclear this decade), stagnant spending on natural gas plants and a levelling off in battery storage investment in 2019, these trends are clearly misaligned with the future needs of sustainable and resilient power systems.

Low investment levels are projected not only with respect to the requirements of the Sustainable Development Scenario, but also in Stated Policy Scenario pathways. While this has not led immediately to serious power supply incidents, longer-term risks need to be addressed now. Further acceleration can be expected in the deployment of VRE sources like wind and solar PV, due to continuing cost declines and government support schemes. Incentives for flexibility from other parts of the electricity system, including grids, demand response and batteries, receive less focus or only indirect attention in policies and regulatory frameworks worldwide, but are, nevertheless, essential.

The case of European and US electricity markets is very illustrative in this sense. In the past decade following the financial crisis, advanced market economies have seen weaker-than-expected growth in electricity demand in general. Due to a combination of a weak economic recovery, stronger policies on energy efficiency and a rapid spread of efficient technologies like LED lights, electricity demand has stagnated or even declined across all advanced economy systems. By 2015 electricity demand in Europe and the United States was 435 TWh (6.2%) lower than initial expectations for recovery after the financial crisis. This had important and positive implications for electricity security: there was a major wave of investment into combined-cycle gas turbine capacity just before the acceleration of wind and solar PV capacity additions. These gas turbine plants were envisaged as running at a reasonably high load factor to supply robust demand growth. Despite this not materialising, they still have the technical capacity for low and flexible utilisation, primarily providing grid services, which they have done as the share of variable renewables increased. Many jurisdictions have implemented changes to their market design, such as Capacity Remuneration Mechanisms or scarcity pricing, as means to recognise the contribution of these resources to security of supply and attract investments to them.

This example is relevant to the electricity security discussion. System operators and markets succeeded in maintaining robust electricity security while the share of variable renewables grew faster than expected. However, this task was greatly facilitated by the large excess capacity of predominantly flexible units. It should be emphasised, however, that this capacity balance was not the result of a conscious design; rather, it was the result of an unexpected structural break. It also led to massive-scale value destruction as utilities wrote down assets and their equity capitalisation depreciated. The combination of weak demand and value destruction of flexible assets shaped investor expectations, creating a reluctance to invest in these assets.

Future policy and technology changes can also trigger structural breaks. However, there is no guarantee that these will similarly lead to lower-than-expected demand. On the contrary, the coming decades of the electricity transition might well lead to a re‑acceleration of electricity demand growth and a substantially higher generation capacity need, in particular due to a trend of increased electrification.

Technological progress has been highly asymmetrical: low-carbon generating technologies like wind and solar PV, and the technologies enabling electrification such as electric car batteries, have progressed more swiftly and witnessed larger-scale deployment than non-electrical low-carbon options like biofuels. In the previous decade, energy efficiency progress compounded the effect of weaker-than-expected economic growth, leading to surprisingly low power demand.

In the next decade, while the macroeconomic downside risk is unfortunately real, electrification might well outweigh efficiency gains; a household buying an electric car on average adds as much electricity demand as dozens of families replacing refrigerators with ultra-efficient models. The impact of direct electrification would be reinforced by an increasing strategic interest in electrolytic hydrogen, which could replace fossil-fuelled end uses such as heavy trucks or industrial heat. The recently announced EU hydrogen strategy targeting 10 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030 would require over 10% of the region’s present electricity generation, which equals the total growth in electrical output during 2000-2010 in a context of stagnation in electricity demand in the recent decade.

In addition to electrification and reaccelerating demand growth, renewables deployment will also have to cover accelerating and nearly unavoidable coal and nuclear capacity decommissioning in many advanced economies. After the value destruction of the past decade, there is little investment appetite for new conventional flexible assets in most mature energy systems. In any case, these may not always be aligned with a credible low-carbon strategy, as is the case for coal. New flexibility enablers from batteries, wider demand response, deeper interconnection of regional systems, new business models and market designs need to fill the gap.

The reliability services required to keep the lights on will need to evolve in response

In addition to controlling total system costs and ensuring necessary investment happens at sufficient pace, policy makers need to take into account that a future low-carbon mix requires dedicated action to ensure a secure system. Regardless of whether countries follow the STEPS or SDS, the share of VRE will be high at a global level and very high in many regions. This implies technical and economic challenges fundamentally different from the ones power systems have faced traditionally.

The integration of VRE can be classified into six phases that capture the evolving impacts, relevant challenges and priority of system integration tasks to support the growth of VRE. While a system will not transition sharply from one phase to the next, the phased categorisation framework can help to prioritise institutional, market and technical measures. For example, issues related to flexibility will emerge gradually in Phase 2 before becoming the hallmark of Phase 3.

Most systems are still in Phases 1 to 3 and have up to 10-20% share of VRE in annual electricity production. The general trend is clear that higher phases of system integration are forthcoming for most countries. Many countries are expected to enter Phase 4 in the coming years.

Some steps are operational in nature, particularly from Phase 4 as the system faces multiple periods with high levels of VRE generation. While any system has its unique characteristics and legacy, exchange of best practices can support progress in many regions. Inertia provides an illustration of this.

A move to solar PV and wind implies a shift from conventional rotating generation to inverter-based generation. Thermal and hydro generation are based on synchronous machines with heavy rotational mass, which provides inertia to the system. In Phase 4, with a high share of VRE, the system faces challenges in maintaining stability. Inertia is a key parameter in system stability. Solar PV and wind generation, but also electric vehicle chargers, batteries and high-voltage direct-current connections, are all inverter based and do not inherently provide inertia. Technology does allow for a variety of very rapid responses to the needs of the system, known as synthetic inertia. Smaller systems (industrial sites and islands) are already capable of operating at very high levels of VRE infeed. But if large-scale systems such as the extent of continental Europe were to be operated with very high instantaneous solar PV or wind penetration (levels above 70-80%, reached in Phase 4), either new technical inverter capabilities would need to prove their effectiveness or additional investment in synchronous condensers would be needed.

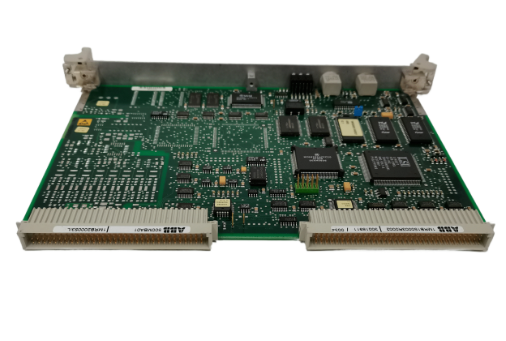

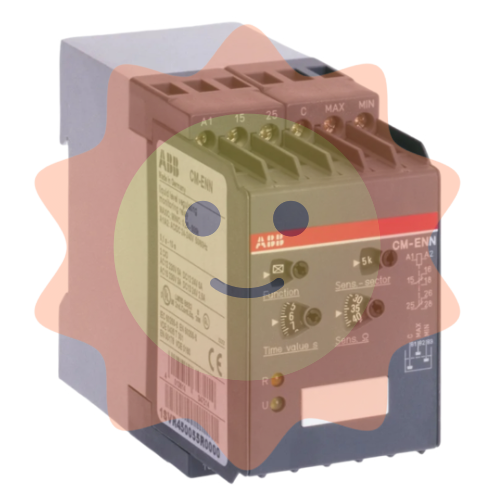

- ABB

- General Electric

- EMERSON

- Honeywell

- HIMA

- ALSTOM

- Rolls-Royce

- MOTOROLA

- Rockwell

- Siemens

- Woodward

- YOKOGAWA

- FOXBORO

- KOLLMORGEN

- MOOG

- KB

- YAMAHA

- BENDER

- TEKTRONIX

- Westinghouse

- AMAT

- AB

- XYCOM

- Yaskawa

- B&R

- Schneider

- Kongsberg

- NI

- WATLOW

- ProSoft

- SEW

- ADVANCED

- Reliance

- TRICONEX

- METSO

- MAN

- Advantest

- STUDER

- KONGSBERG

- DANAHER MOTION

- Bently

- Galil

- EATON

- MOLEX

- DEIF

- B&W

- ZYGO

- Aerotech

- DANFOSS

- Beijer

- Moxa

- Rexroth

- Johnson

- WAGO

- TOSHIBA

- BMCM

- SMC

- HITACHI

- HIRSCHMANN

- Application field

- XP POWER

- CTI

- TRICON

- STOBER

- Thinklogical

- Horner Automation

- Meggitt

- Fanuc

- Baldor

- SHINKAWA